The designer who unmasked Stalinism

David King exposed Uncle Joe's attempts to rewrite the historical record.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

At this moment of historical amnesia, when so many people seem to believe that we are replaying the rise of fascism during the 1930s, it is worth following the lead of Rick Poynor in his new book David King: Designer, Activist, Visual Historian (1), and revisiting the work of this British designer, photojournalist and all-round graphics genius.

Why? Because arguably the most important political achievement of David King, who passed away in 2016, was precisely to combat historical amnesia – specifically, the amnesia organised by the Stalinist rulers of the Soviet Union. To that end, he researched, found, collected and published some of the very best photographs of what really happened under Stalin, as well as what happened before, under Lenin and Trotsky.

As Poynor shows, King was a product of the London art-school scene in the 1960s. Taught by radicals at the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts, he learned to love the montage of Sergei Eisenstein and John Heartfield and managed to interview and publicise the latter. King had little time for the Labour Party and was very hostile to Western intervention in Africa and Vietnam. He also took his fill of Pop Art, as well as appreciating the direct, between-the-eyes approach of the weekly tabloid, the News of the World. Indeed Spitting Image creator Roger Law, with whom King studied the visual techniques of papers like the News of the World, remarks of their partnership: ‘People laugh at tabloid journalism, but when it’s good, it’s a really special skill. We learned all that.’

By 1967, at the age of just 24, King was art editor of The Sunday Times Magazine. He focused fiercely on the content of the stories he directed, being chiefly concerned with politics, crime, art, space exploration, sport and glamour. It was an era in which few worried about the budget for art direction. Articles could run for spread after spread after spread. The slant was questioning, investigative, radical and captivating enough to dominate the Sundays of millions.

It was an era, too, of magazines: Time, Esquire, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Town, Queen. Working with a wave of creatives in the field, some of King’s most singular work was with the photographer Donald McCullin on The Sunday Times. The pair’s spreads on exhausted US soldiers in Vietnam still carry a tremendous punch today.

Yet if his visual journalism was close-cropped, surreally magnified and brilliantly versatile with printing technique, King also had a journalist’s eye for a story. It was King, more than anyone else, who fatally damaged the prestige of Stalinism in the UK, through going to Stalinist Russia in 1970 and, heroically, finding many of the photographs that Uncle Joe had suppressed, retouched, or failed to have burnt.

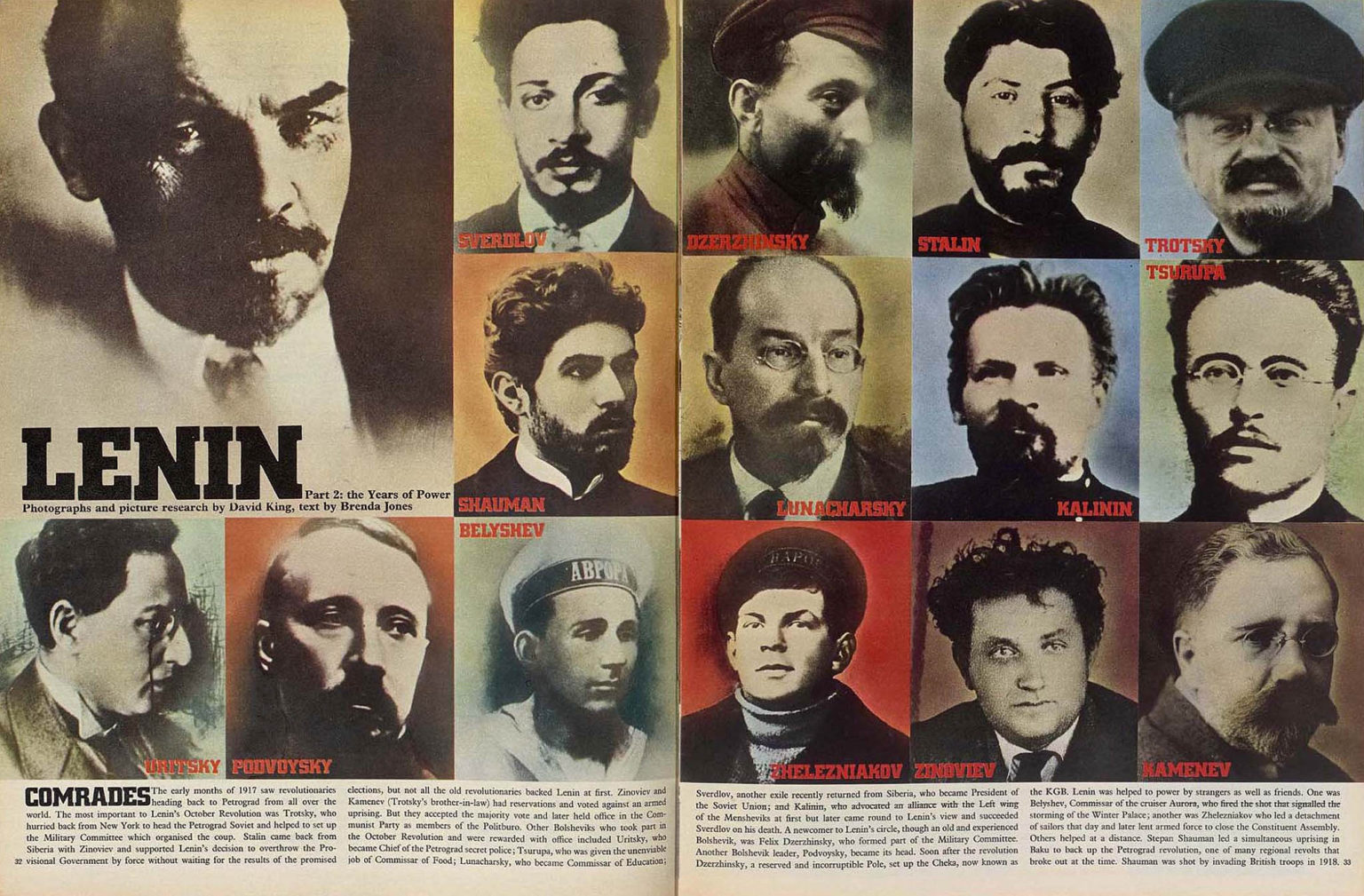

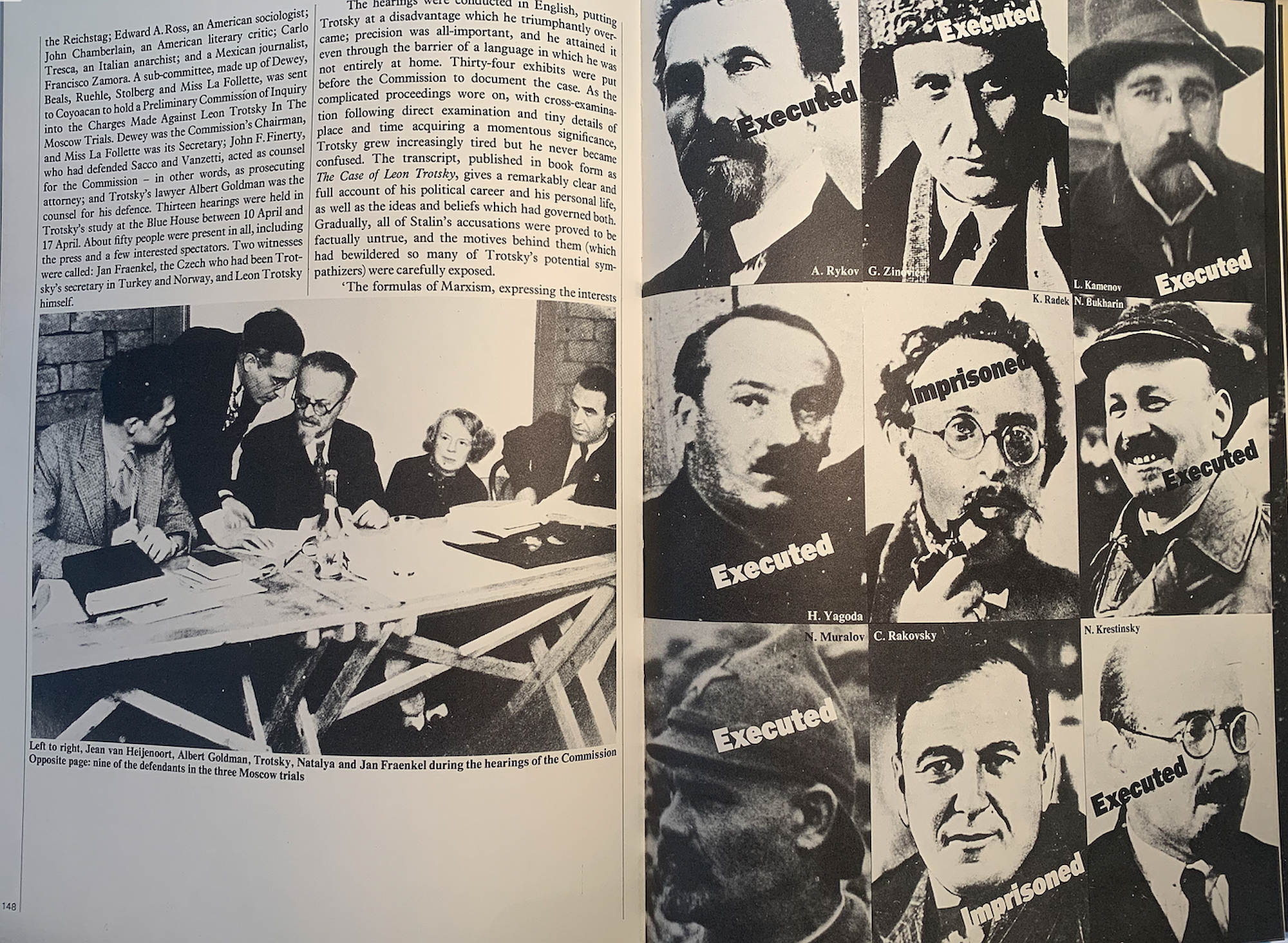

In Trotsky: The Documentary (1972), King and the journalist Francis Wyndham brought home the photographic bacon. After it was published, nobody could easily deny the pivotal role Trotsky had played in the 1905 and 1917 revolutions in Russia, nor his later role as commander of the Red Army. Through King, the long arm of history rehabilitated left-wing and working-class opponents of Stalinism. His principles, and his assiduous search for what really happened, were quite exemplary. Why? Because he paid attention to the politics of 20th-century Russia, and, in everything he did, sought the truth.

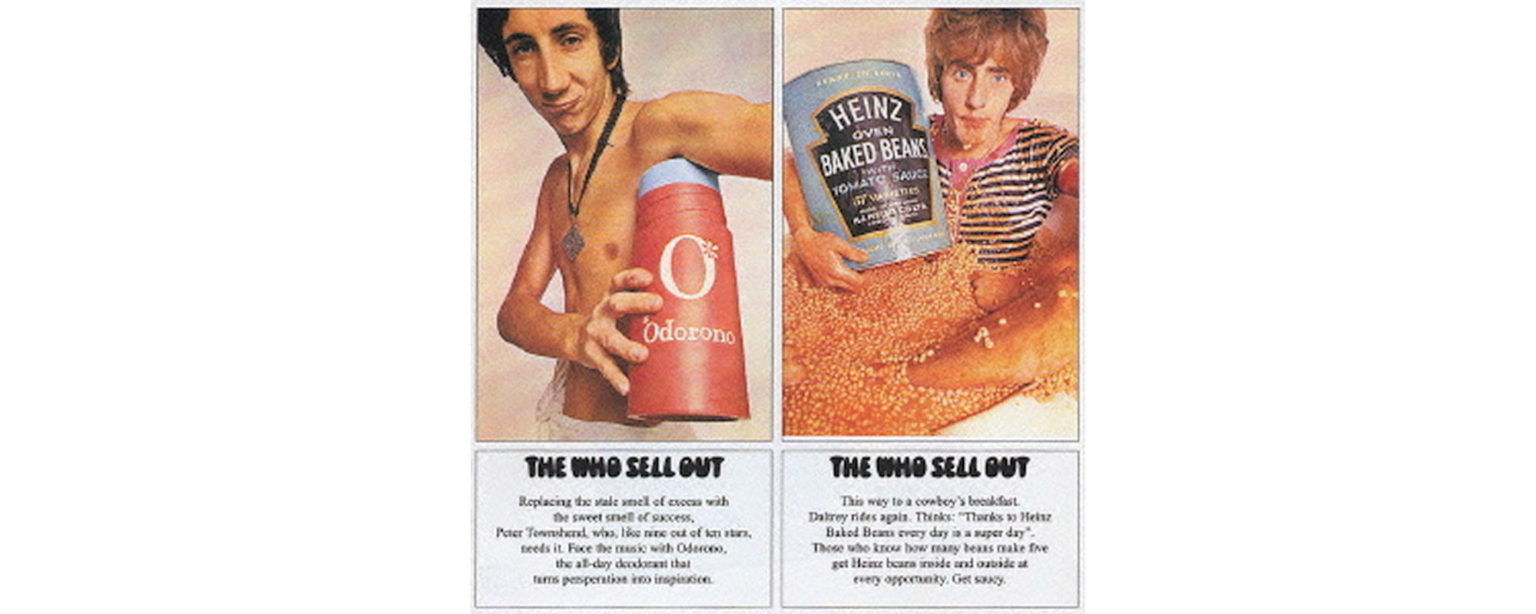

His wackier work also still prompts a gasp. Who really knew that King put together the cover for the Who’s 1967 album The Who Sell Out, with Pete Townshend and an outsize Odorono deodorant stick, and Roger Daltrey in a nearly fatal tub of Heinz baked beans? Who knew that he composed the blitzed psychedelic montage for the record-sleeve of the rare 1968 Jimi Hendrix album, Electric Ladyland Part 1 – or the more famous sleeve for Electric Ladyland pure and simple, the master’s best-selling double album? All this from a man who, just five years later, like Heartfield on steroids, hammed up the covers of learned Pelican editions of Karl Marx with tabloid blow-ups of the bearded giant.

I believe that we can be less grateful, however, for what Poynor describes as King’s visual activism, as contrasted with his visual journalism. To these eyes, King’s work for the Anti-Nazi League, the Anti-Apartheid Movement, the United Nations and the defunct London weekly City Limits, while undeniably striking, is limper and more derivative than his other work. My opinion may be unfairly coloured by the fact that I never liked any of these fashionable causes; but perhaps the weaker design on display here suggests that King himself had his reservations.

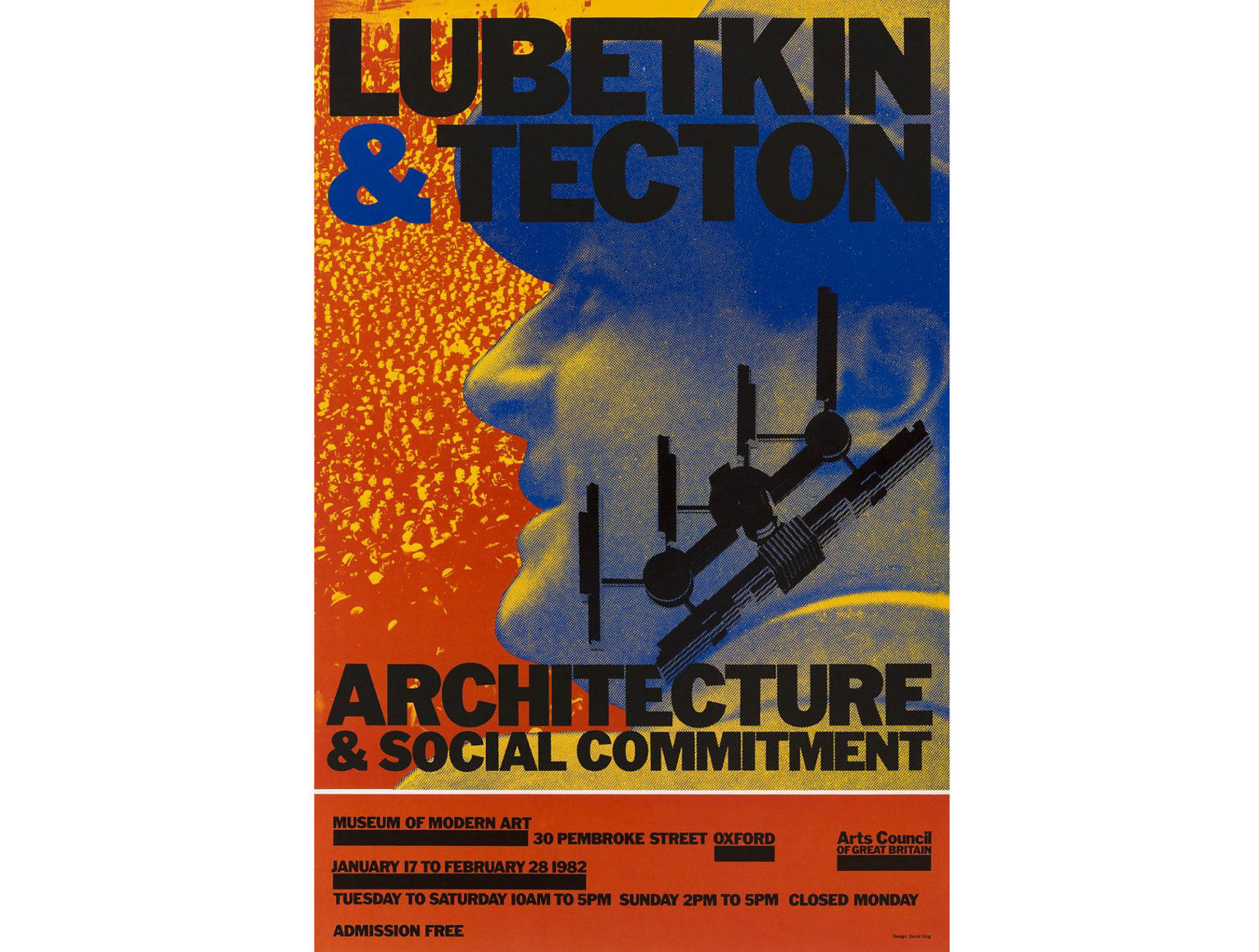

Poynor decides that King’s collaboration with David Elliott, of the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, should be considered visual activism. Still, one can concede that the period of 1979 to 1987, for most of which the two Davids worked together, was influential in bringing Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Mayakovsky to public attention, through MoMA catalogues and posters. Similarly, King’s catalogue Art into Production: Soviet Textiles, Fashion and Ceramics 1917-1935 (1984) did wake people up to the fact that Soviet design had had, beyond graphics, a tremendous record – even for some years after the triumph of Stalin in 1924.

The final part of Poynor’s narrative deals with King’s contribution to visual history. King didn’t only restore Trotsky to his rightful place in the development of Russia; later, in Ordinary Citizens: The Victims of Stalin (2003), he also collected harrowing photographs of those whom Stalin’s regime deemed a threat, and who were summarily shot, often after torture. In both cases, the full extent of King’s achievement needs to be appreciated: nobody else, even in Russia, has ever assembled such a documentary history of the Soviet Union.

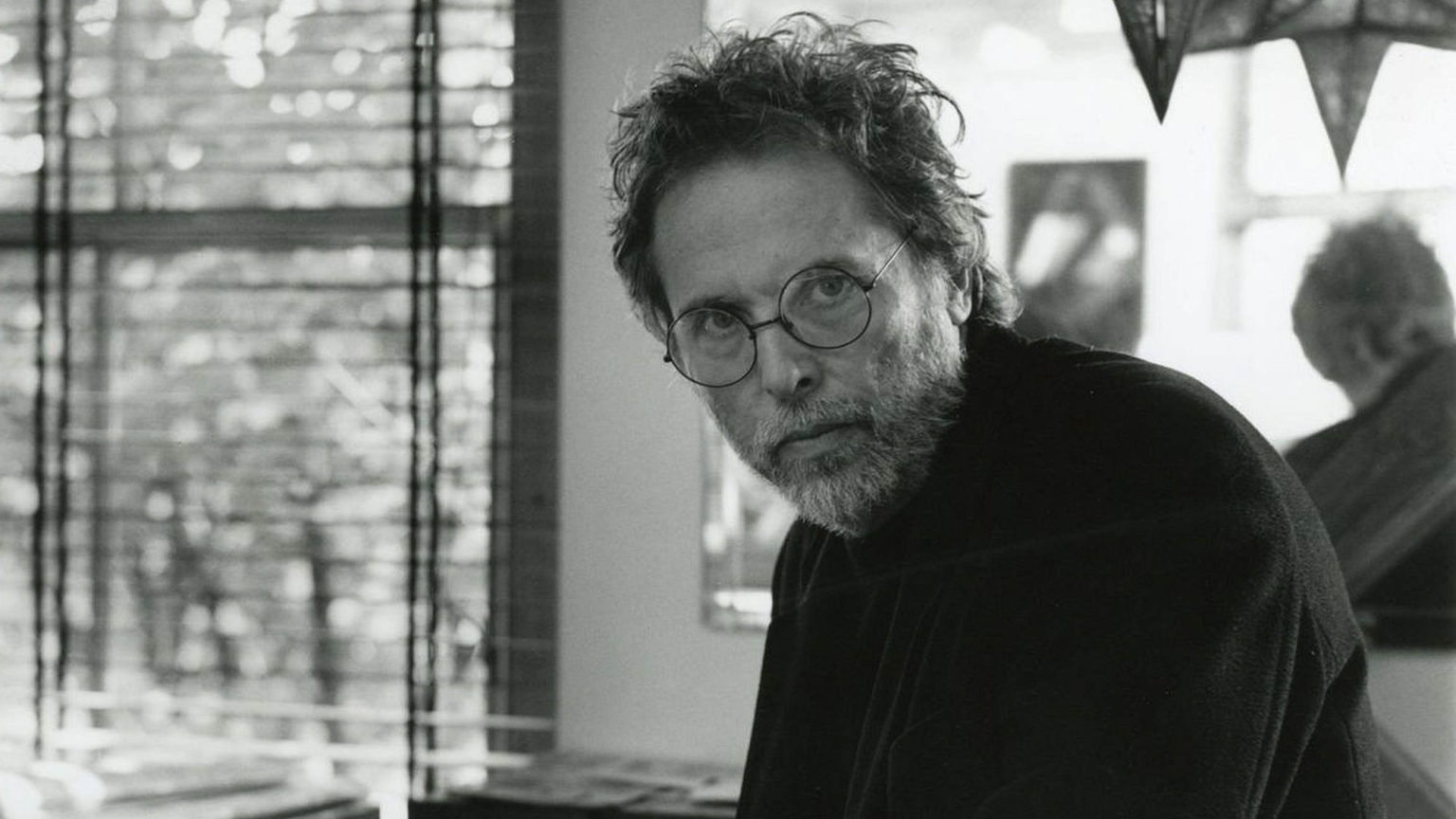

I interviewed King in 1984. He was a good-looking guy, with a typically English manner – a shy man, but firm in his convictions. He showed me some of his enormous collection in that rambling old house he had in Islington. The collection was spread out and piled everywhere, in gelatin prints and all kinds of artwork, in every nook and cranny, along with lots of vinyl records.

King was generous with his time and in his outlook. When, in 1986, I asked him for photographs to illustrate The Soviet Union Demystified: A Materialist Analysis, by spiked regular Frank Furedi, he duly obliged. The result was a delight. King asked for nothing in return, and, in that regard, I still feel a debt toward him. Once again, he contributed brilliantly to the historical record.

King’s loss is a great pity. Still, his designerly brio, his attacking style and his contribution to historical enquiry all live on. King reminds us that lofts, box files, dusty old photo albums, obscure bookshops and ill-lit library shelves contain many truths which words alone cannot quite capture.

The revolution needs its graphics, as much as it needs its writers, thinkers and organisers.

These things need remembering. Everything needs remembering, as accurately as possible. Poynor’s David King lives up to its subject’s magnificent achievement.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University.

David King: Designer, Activist, Visual Historian, by Rick Poynor, is published by Yale University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

A selection of King’s work is on www.instagram.com/davidkingdesigner/

Main image: Guy Hearn.

(1) To declare an interest: in the century gone by, I wrote an article or two for David King’s author, the graphic-design scholar Rick Poynor, and worked more extensively with its designer, Simon Esterson.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.