Sweden is flattening the curve, too

Once again, Sweden shows that hard lockdown is not the only way to get Covid under control.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The best way to trigger people on both sides of the lockdown debate is to mention Sweden. To some, it is a model of how to manage a pandemic without shutting down society for months on end. For others, refusing to implement lockdowns was a reckless strategy with deadly consequences.

When Sweden decided not to lockdown in March, we were told it would lead to nearly 100,000 deaths by 1 July. The actual total ended up being 5,490. Infections and deaths were falling from mid-April, pretty much at the same time as in most other European countries with strict lockdowns.

It is still early to evaluate the economic consequences, but Sweden’s GDP, in the fourth quarter of 2020, was estimated to be 2.6 per cent lower than the previous year, compared with a drop of 4.8 per cent for the EU as a whole.

Ah, but Sweden experienced a higher death rate than its Scandinavian neighbours, people will say. True, but the trends in deaths tell us that the virus was already much more widespread in Sweden than in Norway and Denmark when those countries imposed their lockdowns on 12 and 13 March respectively. This suggests that they may not be useful countries to make comparisons with, despite their proximity.

Arguably, a better example of a similar-sized country to Sweden – where coronavirus had also spread widely early on but which chose to lock down – is Scotland. Currently, Sweden has experienced a Covid-related death rate of 1,170 per million almost exactly the same as Scotland’s rate of 1,168.

At the same time, hopes that Sweden’s experience in the spring of 2020 would mean it would have sufficient herd immunity to avoid a second wave were misplaced. From September, it experienced another significant surge in cases, followed by hospitalisations and deaths.

By December, death numbers were similar to those in April, leading to the Swedish government finally deciding to impose more restrictions. These include limits on opening hours of bars and restaurants, closing upper-secondary schools (for pupils aged 16 and above), and recommending (but not mandating) masks on public transport.

The measures were still very modest in comparison with the restrictions and lockdowns imposed in most other European countries. Many were concerned that they would not be enough to stop the rise in infections. Indeed, governments across Europe assured their citizens that strict lockdowns were the only way to stop a surge in infections and to prevent health services being overwhelmed.

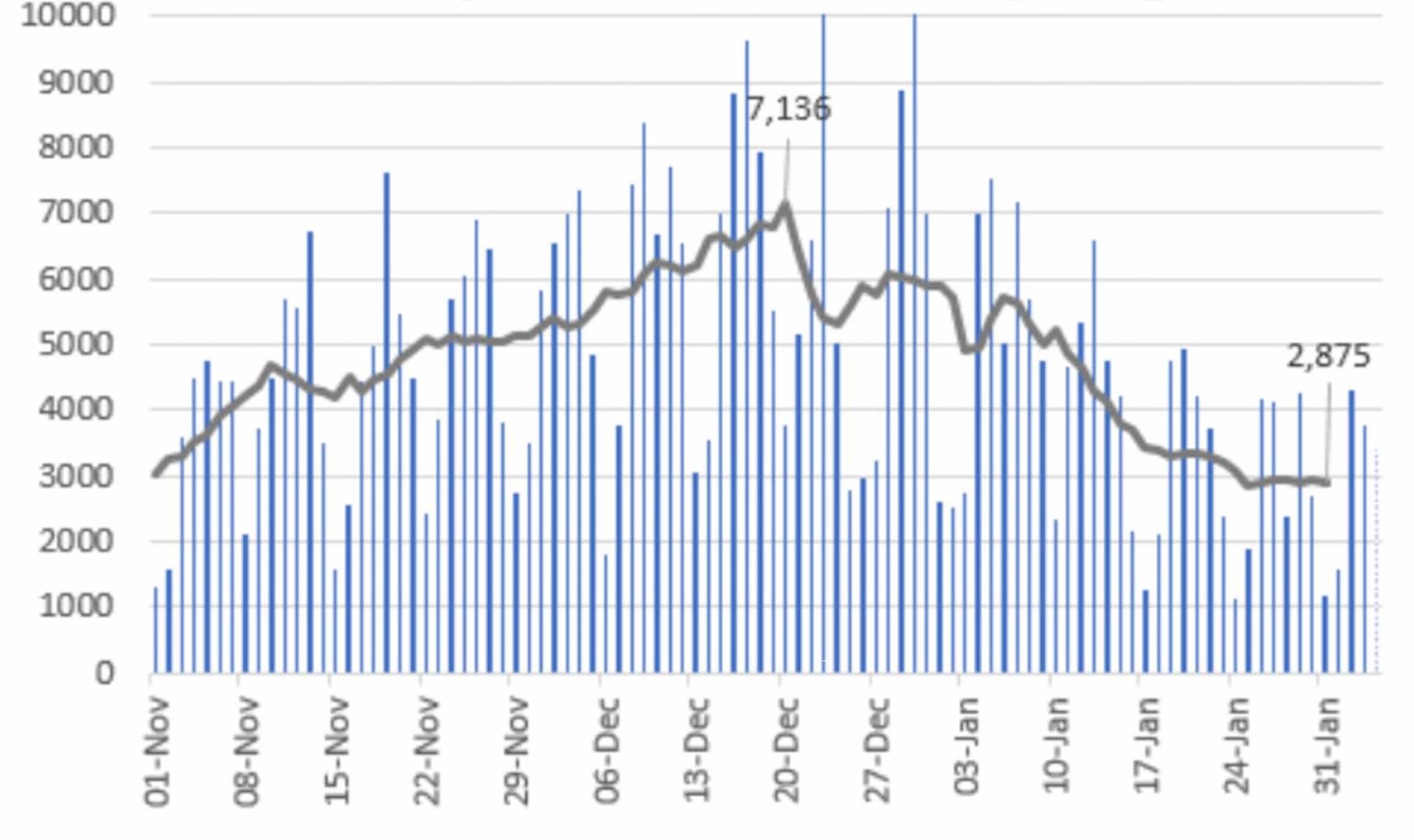

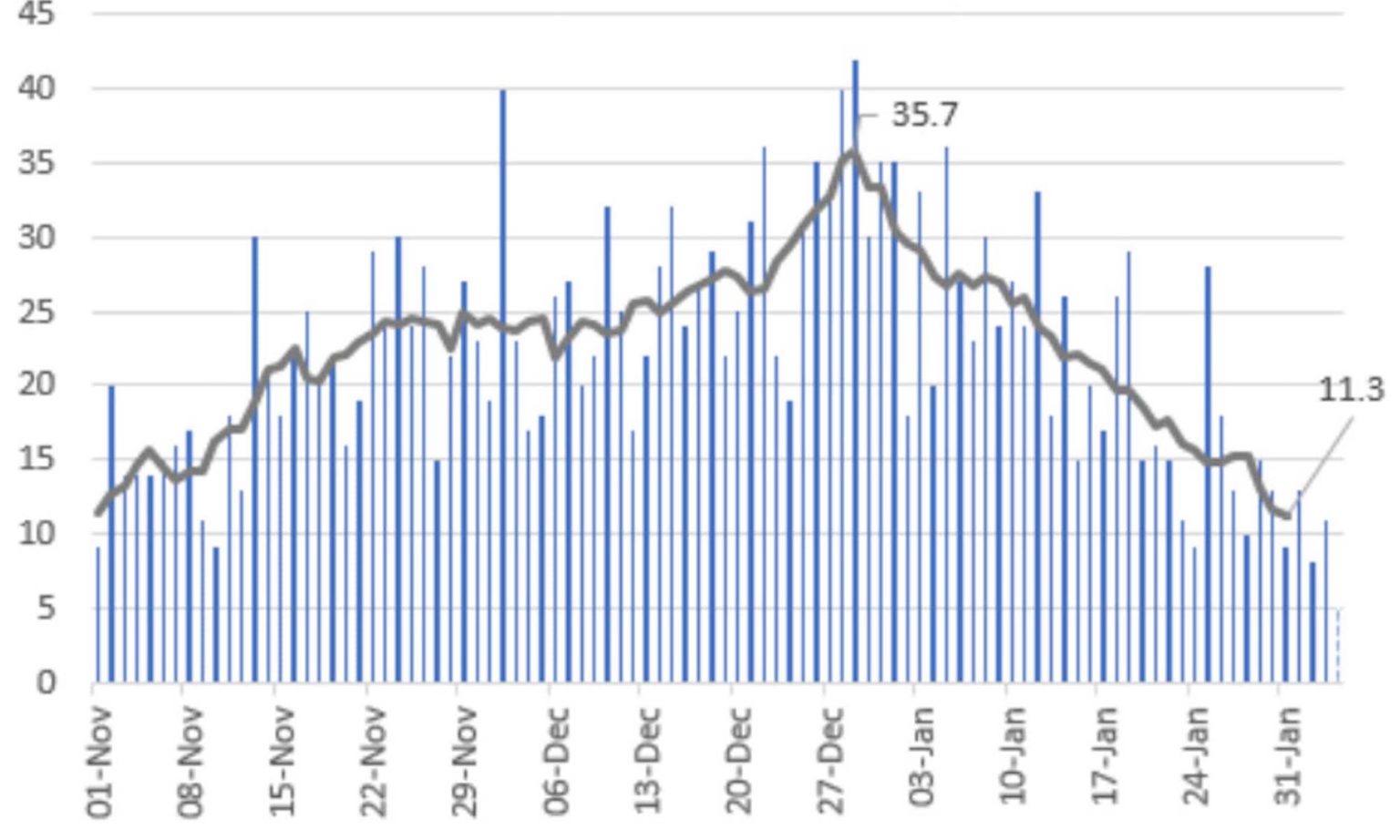

Yet from the end of December, Sweden has experienced the same steady decline in cases as elsewhere. Positive tests have decreased from a peak of 7,136 on 20 December (using the centred seven-day average) to the latest figure of 2,875. That’s a 60 per cent decrease – almost exactly the same as we have seen in the UK.

Given the lag between infection and testing, infections probably started falling from the second week in December. New ICU cases have dropped by even more and deaths are also decreasing, though the long lag in Sweden’s death reporting means death trends take some time to evaluate.

Whether the drop in cases will continue remains to be seen (there are signs that the decrease may have levelled off in the past few days). But Sweden has demonstrated once again that infections can come down and pressure on hospitals can be relieved without resorting to lockdowns.

Did the most recent, limited restrictions cause the reduction? Even that seems unlikely. Upper-secondary schools closed from 7 December, too early to be the cause of the drop in infections. The restrictions on bars came in on 24 December which was also well after infections had started to decrease.

Of course, Sweden has many unique characteristics, so we need to be cautious before assuming its strategy could have been replicated in countries like England or France. But the surprising thing about the trends in Sweden is how similar they are to everywhere else, lockdown or no lockdown.

This winter, cases across Europe have increased and then fallen at similar rates and similar times, irrespective of whether the country implemented strict lockdowns, like Scotland, England and France, or had lighter restrictions, like Sweden or Croatia.

Over in the US, different states have tried different strategies and have reached similar results. Back in September, Florida decided to switch away from a lockdown strategy, ending mask mandates and reopening bars with even fewer restrictions than in Sweden. Cases and hospitalisations in Florida rose in the first half of winter, but, if anything, less steeply than in states like California, which persisted with tight restrictions. From January, Florida’s cases and hospitalisations have decreased just as they have in other states.

Even in England, it is now clear that infections were falling steadily well before the country was put into the current national lockdown. Further, this decrease was experienced across the regions, irrespective of whether they were already under the strictest ‘Tier 4’ restrictions or not.

That Sweden has ended up in a very similar situation to the UK, despite our rolling restrictions and lockdowns, is striking. In itself, that does not necessarily mean that lockdowns have no effect. Perhaps lockdowns accelerate decreases in cases a little, or slow the rate of increase. But even on this, the academic evidence is weak. For example, a recent Stanford University study concludes, ‘While small benefits cannot be excluded, we do not find significant benefits on case growth of more restrictive NPIs [non-pharmaceutical interventions]’ (ie, lockdowns).

Sweden cannot be considered a perfect model for tackling the virus: its failures in protecting care-home residents are well documented, though similar tragedies occured in many other countries, of course.

But perhaps one answer to why Sweden triggers so many is that it raises the possibility that had the UK relied more on guidelines and sensible safety measures, rather than enforced closures backed by criminal law, our hospitalisations and deaths would have peaked at a similar level, but without the terrible economic and social consequences of lockdowns. For some, that possibility is just too awful to contemplate.

David Paton is professor of industrial economics at Nottingham University Business School. Follow him on Twitter: @CricketWyvern. He is also a member of the Health Advisory and Recovery Team (HART).

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.