Understanding Singapore’s Covid miracle

How did a nation that locked down so late become the success story of the pandemic?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Something close to a miracle occurred in Singapore in 2020. At the time of writing, Singapore has recorded 59,602 cases of Covid with just 29 deaths. At just over 10,000 cases per million, the cases are well below those of the US (80,232 cases per million), the UK (57,198) and France (50,710). Moreover, the vast majority of Singapore’s cases are concentrated in the foreign worker dorms, while community cases have been limited to just over 6,000.

Moreover, Singapore’s Covid-related death toll is staggeringly low, with its infection-fatality rate standing at just 0.05 per cent. Little wonder many have noted that Singapore has controlled the outbreak of Covid remarkably well. Yet very few have noted how unlikely an outcome that was. Even David Chan, a professor of psychology at Singapore Management University, in his hurriedly written book on the Singapore outbreak, Combating a Crisis, misses how spectacular an outlier Singapore is.

Several reasons for Singapore’s outlier status have been proposed, including: mask wearing, tight border controls, lockdown measures, and contact tracing with the associated app, TraceTogether. As implied by the extended title of Chan’s book – The Psychology of Singapore’s Response to Covid-19 – he claims that the success of Singapore’s Covid response was, at least in part, due to good psychological management of ‘negative emotions’, and ‘building psychological capital’ and trust via, for example, campaigns to maintain personal hygiene and to safe-distance, and clear government communication and assurance.

However, the ultimate reason why Singapore has suffered so minimally from the Covid outbreak is mysterious, and may ever remain so. Out of all the possibilities put forward, good contact tracing is likely the most important in stemming community spread of Covid, although, as we will see, the TraceTogether app played no role in that. The other vitally important measure that Singapore took was to protect care homes, something that has not been widely commented on and that Chan does not mention anywhere in Combating a Crisis.

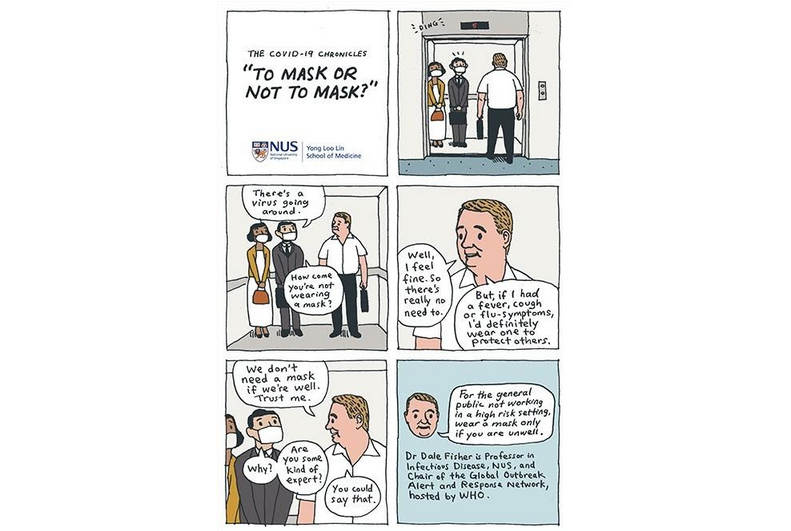

Government communication in Singapore has been less chaotic than it has been elsewhere, notably in the UK and the US. It was not, however, entirely smooth, and communication regarding face masks was notably mixed. Indeed, face masks were a rare sight before January 2020, and at that time the official advice to residents was not to wear a mask. At the end of January, Singapore’s prime minister Lee Hsien Loong advised Singaporeans not to wear a mask unless they were currently sick. That advice was supported by a national information campaign from the National University of Singapore School of Medicine (see the cartoon below). Mask sales surged (despite government instruction) in late January, and then eased again until the advice was reversed in early April. Mask wearing was rare before January 2020 and then patchy until it was enforced on 14 April, and so widespread mask-wearing before the outbreak cannot explain Singapore’s extreme outlier status.

Singapore is a major travel hub and welcomes close to 20million overseas visitors every year. Between October 2019 and March 2020, close to 7.5million visitors entered Singapore from overseas, with roughly 20 per cent of them coming from mainland China. Singapore did not close its border to tourists until 24 March, one week after Rome closed its main terminal. Thus, as for other major international travel destinations, including Rome, London and New York, Singapore will have received guests who moved freely throughout the city with Covid for at least three to four months (and many of them not wearing masks). Temperature screening set up at the end of January at Singapore’s airport might have made some difference, but it would not have detected asymptomatic cases. Tight border control cannot explain Singapore’s extreme outlier status.

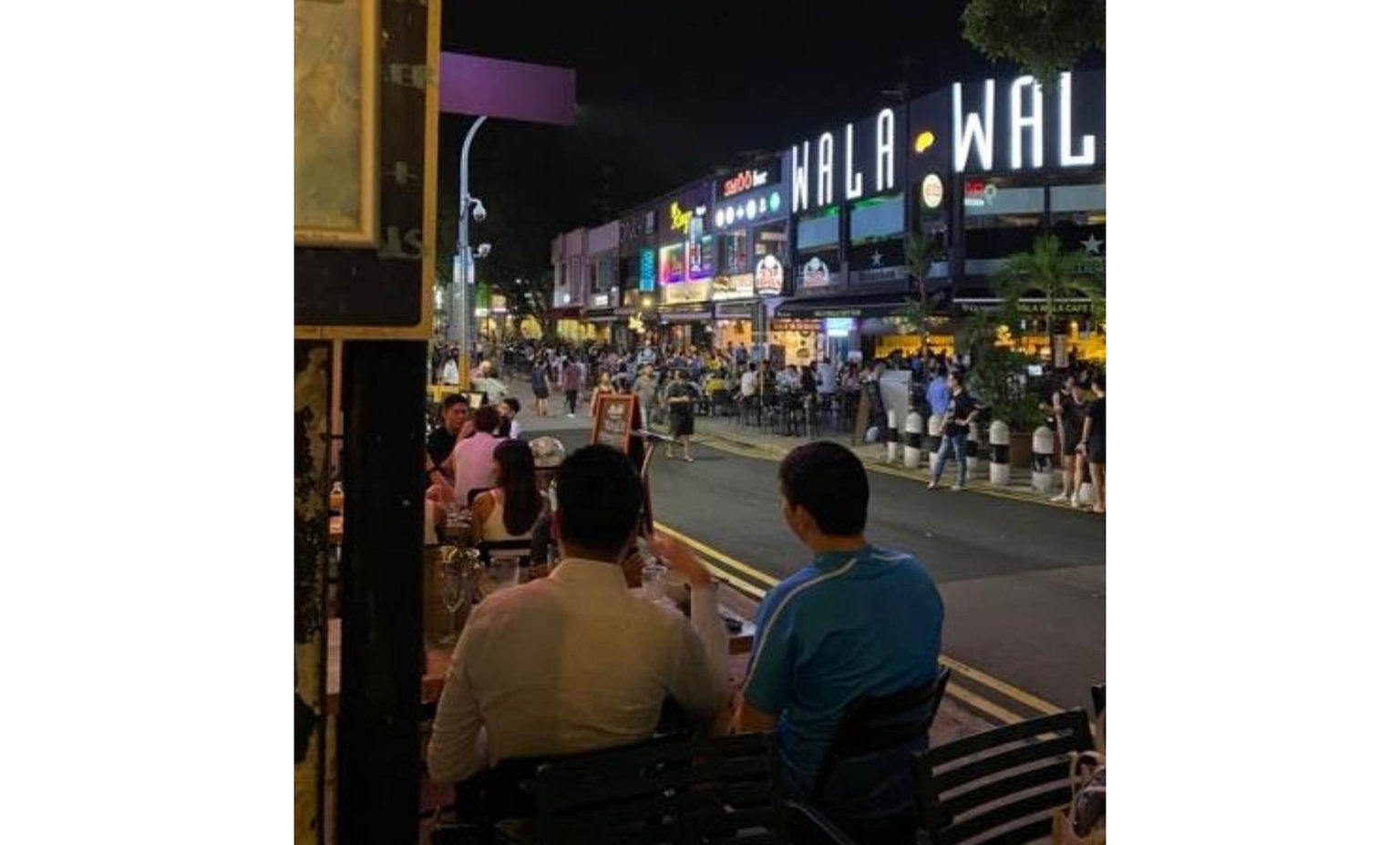

Singapore is also densely populated; people live and socialise in close proximity. Few people cook at home because eating out is so cheap, and the weather is conducive to being outdoors. I took the picture below on 25 March in a popular night spot known as Holland Village. Note the density, the close proximity of tables and the lack of mask wearing. The national lockdown, known here as a circuit breaker, did not come into effect until 7 April, almost a month after Italy, and about two weeks after New York City and the UK. A widespread tendency to distance or an early lockdown cannot explain Singapore’s extreme outlier status.

Singapore’s highly effective track-and-trace systems provides a more promising explanation. Singapore learned several lessons from the SARS outbreak in 2003, including: that the transfer within hospitals was a central problem (UK, take note); and that temperature monitoring and isolating those with a fever, along with their contacts, was the best way to prevent community transmission.

Beginning in January, temperature screening became more common, and by early February daily screening was mandatory at most workplaces and for entry to most shopping centres, bars, restaurants and other crowded areas. Anyone with a fever was required to isolate for two weeks. Most public places also required patrons to declare their entry using their mobile phones to register via a SafeEntry QR code. Anyone diagnosed with Covid was interviewed regarding their whereabouts and their SafeEntry records were inspected. Close contacts were identified and quarantined. The hotspots identified by SafeEntry were also reported and people were advised to self-isolate if they had been in those areas during certain periods.

Singapore launched its own contact-tracing mobile app known as TraceTogether on 21 March. TraceTogether works via Bluetooth to record other phones using TraceTogether in close proximity. In the event of a user being diagnosed with Covid, the records can be downloaded by government officials and those who were in proximity can be alerted to either isolate or be tested.

Chan notes that utilisation of the TraceTogether app was far below what was needed in order for the app to be useful. There were several initial problems with the app, including the general difficulty for older people in navigating their smartphones, and some did not own one. The app was also incompatible with some phones, especially the iPhone. And it also had a tendency to drain phones’ batteries. The government addressed those problems by introducing a wearable app for people to carry around with them.

Nevertheless, take-up of the app (and wearable device) remained at around 25 per cent in March, far below the 75 per cent needed to make it useful. Human-interview contact tracing might have contributed to Singapore’s extreme outlier status, but smartphone tracing did not.

The major barrier to use of TraceTogether was a concern about privacy. As Chan notes:

‘The news on developing the wearable device and the updated TraceTogether app to collect users’ personal identification numbers evoked considerable negative feedback on social media, including an online petition which garnered more than 40,000 signatures within a short span of only a few days.’

People were concerned about the government having access to their location and who they were with. Chan considers that concern misguided because the government will only obtain the data where a person has been in close contact with a case. And besides, who wouldn’t want potentially life-saving intervention to protect them from Covid?

Well, the person having a secret affair, or moonlighting on their boss, or not working entirely legally or being with other people not working entirely legally. Even in Singapore, people can step outside the rules either on purpose or by accident, and Singapore is not known for leniency when it comes to those who don’t follow the rules, whatever the reasons might be. Governments globally have also breached privacy accidentally through the misplacing of records, or deliberately to counter crime or terrorism. Given all this, people’s reluctance to download a tool of state surveillance on to their phones is hardly a surprise.

Regardless of the reluctance to use TraceTogether, it is clear that Singapore implemented strong techniques to prevent Covid transmission. The worker dorms, however, were not included in the efforts. There are over 300,000 foreign workers residing in worker dorms in Singapore. Workers come from Malaysia, Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Burma, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and China and largely perform construction and other manual labour jobs that employers claim Singaporeans are unwilling to do – at least for the wages they offer.

The worker dorms provide, as Chan described, ‘crowded communal living… A typical dormitory has between 12 and 16 workers living together in a room with beds spaced less than one metre apart.’ Such crowding is perfect for spreading an infectious virus like Covid, and it spread impressively. Based on PCR and serology testing, just under half the workers were infected. Of those infected, just over a third showed symptoms, 25 were admitted to ICU, and two tragically died.

So, overlooking the threat of infection in the worker dorms was an error on the Singapore government’s part. But it was one that had relatively minimal health impact because the workers were young and healthy. Errors that allowed Covid to spread through care-home populations, notably in the UK, Sweden, and elsewhere, were vastly more destructive.

Around 12,000 Singaporean citizens live in care homes, compared with around 418,000 UK citizens. That equates to about 0.3 per cent of Singapore’s population (citizens only) and about 0.6 per cent of the UK’s. Outbreaks of Covid in care homes in the UK and elsewhere have had a devastating impact, but that has clearly been avoided in Singapore.

Indeed, shortly after the first case of Covid was detected in a care home on 31 March, Singapore’s Ministry of Health moved around 3,000 nursing home employees into hotels to isolate them from the wider community, and tested all 9,000 nursing-home staff. Positive tests were followed by contact tracing and quarantine. Those measures were in addition to a month-long ban on visitation, safe-distancing in all homes, and zoning. Singapore has reported only three Covid-related care-home deaths, compared with estimates of 25,000 Covid-related deaths in the UK.

In summary, then, Singapore implemented an effective track-and-trace system with associated quarantine. That system did not rely on the TraceTogether app. An app might be cheaper and easier to implement than manual track-and-trace, but that is still to be proven and the privacy concerns remain.

Early adoption of masks and lockdown were not a feature of Singapore’s response to Covid, and so early mask adoption and early lockdown did not make the difference. Whether the later adoption of masks has helped prevent any further spread, and whether the lockdown was necessary to prevent a wider community spread, will be answered by further scientific and historical enquiry. Strong protection of care-home staff and residents, however, clearly contributed to the remarkably low death rate.

Chan’s broad suggestion that psychology played a special role in Singapore is only true in a narrow sense. Adoption of the TraceTogether app is rising, nudged along by the government making further relaxation of the Covid rules dependent on more people adopting the app and by linking the app to the SafeEntry procedure. Soon it will not be possible to shop, go to a restaurant, or enter most public buildings and places unless the app is activated and running. It doesn’t require much psychological knowledge to understand why people conform with measures that are required for many everyday activities. As Chan explains, the authorities have been prepared to ‘explicate, elaborate, educate, engage, and enforce’ (my emphasis). So, although Singapore’s success in dealing with Covid is impressive, it has relied on compliance with strict laws that might not transplant across borders. Attempting to reproduce Singaporean approaches to Covid in London, Rome or New York could generate a considerable amount of what Chan calls ‘negative emotion’.

Stuart Derbyshire is an associate professor of psychology at the National University of Singapore.

Combating A Crisis: The Psychology Of Singapore’s Response To Covid-19, by David Chan, is published by World Scientific Publishing. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

All images, unless otherwise credited, by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.