Brief immunity to Covid? Not so fast

A widely reported study tells us nothing we didn’t know – and certainly does not make the case for lockdown.

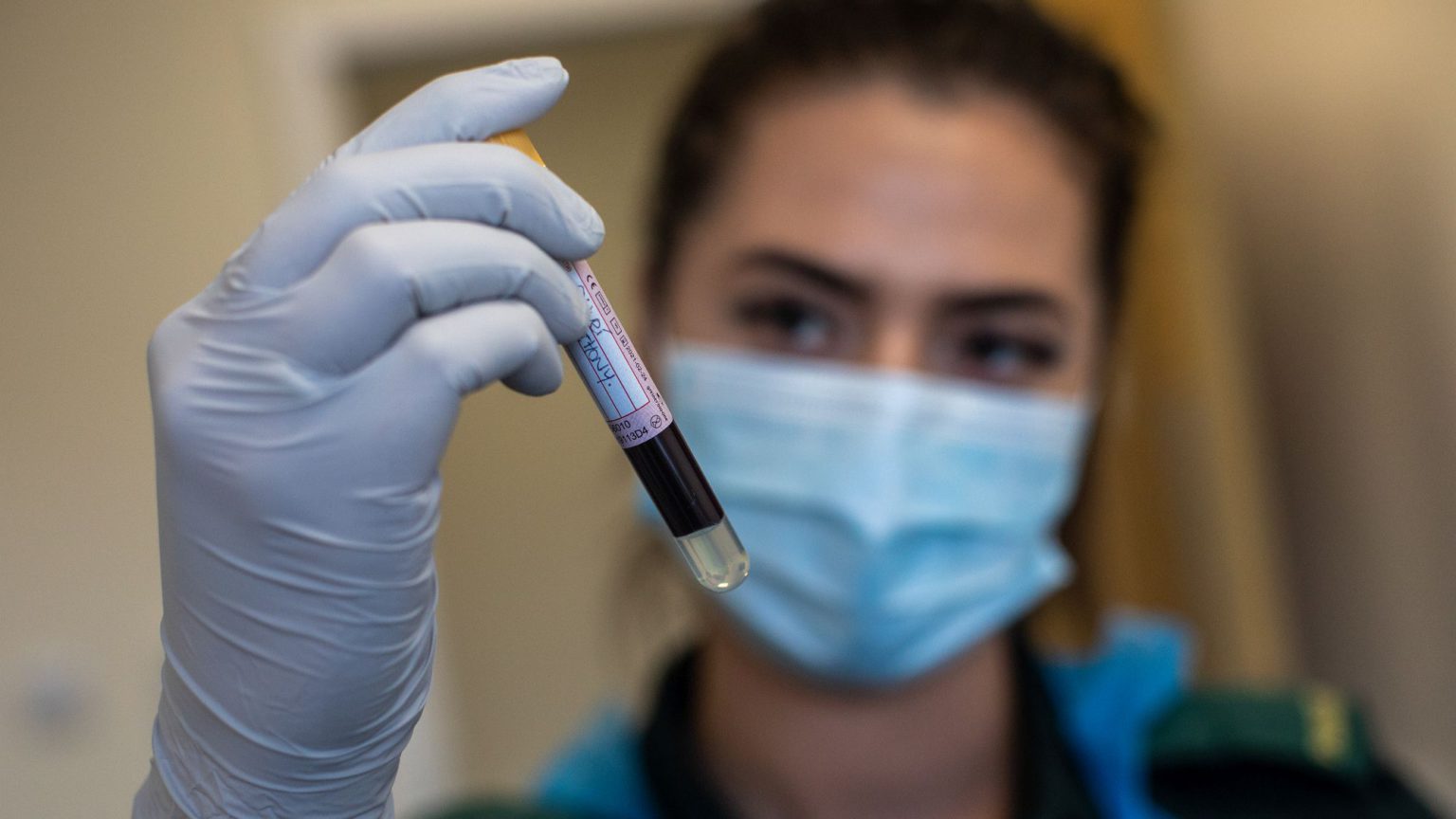

BBC News led on Tuesday with the news that ‘Covid: Antibodies “fall rapidly after infection”’. The implication was that this was a devastating new piece of information. It’s not and it probably doesn’t matter much.

The project, Real Time Assessment of Community Transmission (REACT), is led by researchers at Imperial College London. For this paper, they tested 365,000 people with a self-administered pin-prick blood test. The speed of the test allowed a huge number of people to be checked in a short space of time, between 20 June and 28 September.

The headline result was that the proportion of people found to have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, fell from around six per cent at the start of the study to 4.4 per cent by the end. Interestingly, 30 per cent of the people found to have antibodies reported no symptoms.

There are a few limitations to the study. The test is quick, but not very subtle. It doesn’t measure the levels of antibodies in someone’s blood, merely whether there are enough to produce a ‘positive’ result. So some of the ‘negative’ results could be in people with low levels of antibodies. Nor did the study follow the same group of people, but rather continued to test for the general prevalence of these antibodies.

Two factors that seem to influence the presence of antibodies are age and the severity of the disease. There was more of a decline in the presence of antibodies in older people, while those who had more serious illness had a higher level of antibodies. Those who may have had on-going exposure to the virus, like healthcare workers, seemed to retain antibodies better than others.

At the beginning of the crisis, many (including me) assumed that when antibody tests arrived we would have a clearer idea of who had been exposed to the virus. There were even suggestions that those who had been infected and tested positive for antibodies might get some kind of ‘passport’ to escape lockdown restrictions.

But this was a bit simplistic. In fact, it has long been known that antibodies to coronaviruses decline over time. Moreover, several other studies have already observed this phenomenon in relation to Covid-19. So the REACT study is useful, but on those headline conclusions, it is really just confirming things we already suspected.

Another thing to note is that we shouldn’t read these results to conclude that only six per cent of people ever got infected. Some of the participants may have had the disease early on, got over it with mild or no symptoms, and their antibodies (if any) had disappeared by the time testing for REACT began.

The most common interpretation of the study is that immunity itself declines quickly. But that’s not obvious at all, because there are other mechanisms for dealing with infection: white blood cells called T cells and B cells. Different types of T cells both kill infections directly and trigger B cells to produce antibodies. So long as there is a kind of T-cell memory to previous infections, our bodies can respond when we are confronted with the same infection again.

In an article on Covid-19 immunity, Professor Danny Altmann of Imperial College London notes: ‘With other coronavirus infections, such as SARS and MERS, the hypothesis has always been that T-cell responses offer far more durable protection.’ For example, ‘researchers in Singapore analysed people who had SARS 17 years ago and demonstrated that they still have rip-roaring T cell responses to the virus. This suggests that T cell responses can be quite long-lasting and that they might offer a more definitive way of showing who has been infected and who hasn’t.’ But he adds a note of caution: ‘The only catch is that researchers haven’t proved that T cells in their own right are protective.’

If immunity declined quickly, we might have expected to see far more evidence of repeat infections. After all, we believe there have been at least 43million cases of infection so far, worldwide. Given the lack of testing in many places during the early stages of the pandemic, the true number of infections is probably far higher. Yet there have been just a handful of cases of suspected reinfection. It certainly seems to be unusual so far.

Moreover, if there is no lasting immunity to natural infection, where does that leave us when it comes to vaccines? After all, lockdowns are only a delaying tactic to keep case numbers down until a vaccine (or a cure) comes along. Experts say that it could be different with vaccines because they contain adjuvants, which magnify the immune response. Nonetheless, if the problem of declining immunity is real, the upshot may be that vaccinations may need to be delivered regularly, like the annual flu shot.

For the moment, it seems more reasonable to assume that infection leads to immunity – if not for life, then at least for a significant period of time. The REACT study doesn’t really solve the conundrums of immunity in relation to Covid-19. While some are concluding that we should simply carry on following government rules, it would be wrong to use this study to write off alternative strategies for dealing with the pandemic. In particular, it doesn’t tell us anything more about the feasibility of protecting vulnerable groups while allowing the rest of us to be exposed and thus reducing the spread of the virus – the ‘herd immunity’ strategy.

We shouldn’t become demoralised at the prospect of never-ending restrictions on our lives. One way or another, we will learn to live with Covid-19, whether it is through natural immunity bringing cases down, vaccination or both. Whether we can, or should, live with the consequences of continuing lockdowns, in terms of the economy and freedom, is another matter.

Rob Lyons is convenor of the Academy of Ideas Economy Forum.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.