The harm in hate-crime laws

The Law Commission's embrace of identity politics is bad news for freedom and equality.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Identity politics has long been enshrined in law. A complex mess of equalities legislation, public-order and criminal-justice acts, enacted over the course of several decades, have reduced people to ‘immutable characteristics’, such as skin colour or sexuality, each with associated degrees of privilege or oppression. But, if proposals now set out within the Law Commission’s recently published consultation on hate-crime laws make it on to the statute books, we had all better start swotting up on critical race theory and intersectionality.

Hate-crime laws protect some and criminalise others. Those found guilty of a crime receive a harsher punishment if they are perceived to have been motivated by hatred of their target’s disability, race, religion, transgender identity or sexual orientation. This creates legal double standards. If two violent thugs beat someone up, each dishing out the exact same injuries, they could be punished differently depending on the identity of their victim.

Bizarrely, not only is intent irrelevant to hate crime, but so too is the existence of a victim and the carrying out of a criminal act. As Harry Miller, a former police officer from Huddersfield, found out to his cost, you can be investigated and recorded as having committed a ‘non-crime hate incident’ without having broken the law and without there being any particular victim. Last year, Miller tweeted a limerick ridiculing the notion that people can change sex on a whim. For this, he was visited by the police at his place of work and formally warned about his behaviour.

The Law Commission’s latest consultation aims to simplify and clarify the raft of legislation that hate crime currently falls under. In practice, this means expanding the law to protect more groups and criminalise a broader range of speech and behaviour. The ideology driving this expansion, illustrated by the quotations from choice academics that pepper every page of the consultation, seems cut and pasted from an undergraduate critical-theory module.

In considering the distinct harm of hate speech, the consultation points to arguments that victims perceive ‘their experience as an attack upon the core of their identity’. In relation to acts of racist hate crime, this means that ‘black-minority victims of racist crime will experience the crime more acutely than white-majority group victims because the crime serves as a painful reminder of the cultural heritage of past and ongoing discrimination, stereotyping and stigmatisation of their identity group. When an anti-black racist hate crime occurs, it brings all of the dormant feelings of anger, fear and pain to the collective psychological forefront of the victim.’ This is a view of crime that could have been lifted straight from the pages of Words That Wound, a 1993 book offering one of the first analyses of critical race theory.

Elsewhere, we get Foucault 101. Hate crime, we are told,

‘is a mechanism of power and oppression, intended to reaffirm the precarious hierarchies that characterise a given social order. It attempts to recreate simultaneously the threatened (real or imagined) hegemony of the perpetrator’s group and the “appropriate” subordinate identity of the victim’s group. It is a means of marking both the Self and the Other in such a way as to re-establish their “proper” relative positions, as given and reproduced by broader ideologies and patterns of social and political inequality.’

If all this academese seems confusing to the average man on the street, we need not worry. The whole point of hate-crime law, the Law Commission tells us repeatedly, is to educate the public.

The consultation proposes that ‘gender or sex should be a protected characteristic for the purposes of hate-crime law’ because this would have ‘declaratory importance’. Making misogyny a hate crime would send a message, ‘that culturally endemic negative attitudes towards women are not acceptable’. In such instances, the law is assumed to have ‘educative value’: ‘After a bias incident, there is often discussion about the crime that serves to educate the public. If sexual assaults were appropriately labelled as hate crimes, a similar discussion could occur in regard to rape and other forms of gender-motivated violence that would educate the public about the actual nature of rape and discredit common rape myths.’ In other words, the law needs to change in order to educate the British public into holding the ‘correct’ views.

The ‘correct’ view, it seems, is to affirm the identity of protected groups. The Law Commission flags up a problem with current hate-crime legislation – namely, ‘the lack of acknowledgment of the intersectional nature of victims’ characteristics’. Helpfully, it explains that ‘by “intersectional” we mean the fact that some people experience multiple and overlapping forms of discrimination and abuse’. Of course, this desperate bid to recognise and affirm every identity group leads to a clamour from campaigning groups that want the law extended to protect their members. Commissioners met with ‘older people, homeless people, sex workers, members of alternative subcultures, and those who adhere to non-religious philosophical beliefs. They argued that there is considerable unfairness in the fact that they are excluded altogether from the protection offered by hate-crime laws.’ Likewise, ‘disability groups shared the concerns of LGBT groups about unequal treatment in law compared with race and religion, and the practical and symbolic implications of this’.

The Law Commission’s consultation on hate crime drips with contempt for the British public: we are either hateful and in need of re-education, or pathetic and in need of protection. We already have laws shaped by identity politics, and the proposals put forward by the Law Commission take us further into identitarian terrain. Both free speech and equality before the law are casualties of this. Rather than protecting free expression, the consultation heralds the fact that ‘hate-speech law sets the parameters of morally acceptable speech’, and can therefore ‘represent a permissible interference with freedom of expression’. Meanwhile, equality before the law becomes reinterpreted as equal protection for different victims.

Incredible as it may seem, this new consultation threatens to make a morass of bad laws even more illiberal.

Joanna Williams is currently researching hate crime in her role as director of the Freedom, Democracy and Victimhood Project at the think tank, Civitas.

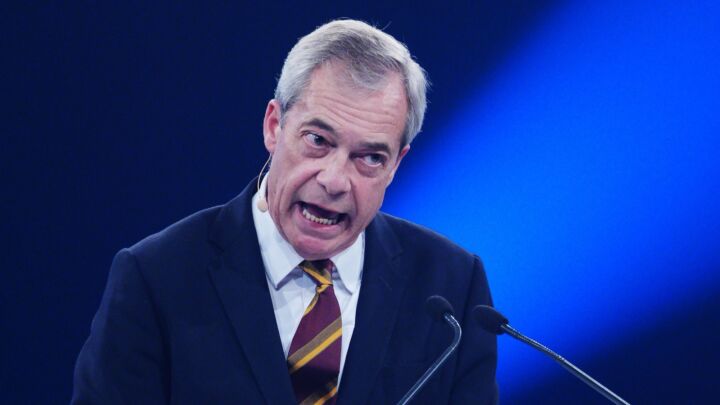

Picture by: Getty.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.