Long-read

Populism: America’s radical tradition

Populism has been dismissed as inherently right-wing and racist. Thomas Frank’s The People, No explains why that’s rubbish.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Populism, with or without prefixes like ‘right-wing’, ‘authoritarian’ or ‘nationalist’, now functions as little more than a pejorative. Publishing houses churn out academic-penned titles like The People vs Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It, Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy, or Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream. High-powered think-tanks talk darkly of the ‘populist threat to democratic norms’. And politicians, from Tony Blair to Barack Obama, talk up populism as a grave challenge that the liberal world order must confront if it is to survive. Even the Catholic Church has had a pop, with Pope Francis declaring that ‘populism is evil and ends badly’.

For the leadership class of politicos, think-tankers, academics and broadsheet pundits, their cries echoing endlessly through the Twittersphere, there is no doubt: populism is a very bad thing. Its signal manifestations, from Trump to Brexit, are presented as the ugly white faces of the all-too-common man. They show his bigotry, his lack of education, his susceptibility to charlatanry and Facebook ads. They express his nostalgia for a time when his nation was great, and his loathing for all those newcomers who have ruined it. And, ultimately, they show why this common man is wholly unsuited for this democracy lark.

That at least has been the song played on loop by the political and media class over the past four years. Which is why Thomas Frank’s The People, No: A Short History of Anti-Populism (entitled People Without Power in the UK) is such a vital intervention. Because here Frank, author of What’s the Matter with Kansas? and a long-time scourge of liberal hypocrisy, rents the veil on today’s populism scare, showing how it arises, as he puts it, ‘from a long tradition of pessimism about popular sovereignty and democratic participation’.

And, through his focus on American politics and history, Frank attempts something else, too. He argues that populism, a politics grounded on the common interests and desires of the people, far from being the preserve of right-wingers, authoritarians and outright racists, has traditionally been – as it still ought to be – the preserve of the American left. For ‘populism is not only a radical tradition, it is our radical tradition, a homegrown left that spoke our American vernacular and worshipped at the shrines of Jefferson and Paine rather than Marx’.

America’s forgotten radical tradition

Some may carp that Frank’s concentration on the US leads him to ignore other self-styled populist movements around the world, such as the Narodniks in 19th-century Russia. But no matter. Frank’s argument for the often radical, sometimes reformist, roots of populism in the US, inspired in part by Lawrence Goodwyn’s 1978 classic The Populist Moment, is both compelling and historically convincing.

As Frank tells it, the very word ‘populist’ was coined in May 1891 by Kansan delegates heading home from a conference of the then fledgling People’s Party. ‘On that fateful train ride – and in conversation with a local Democrat who knew some Latin – this bunch of Kansans came up with [a word to describe supporters of the People’s Party]: “Populist”, derived from populus, meaning “people”.’

It made sense. The People’s Party was the political representative of a genuinely mass movement, initially formed by the millions of disenfranchised, impoverished farmers and agricultural labourers of the Farmers’ Alliance, before they were joined by the Knights of Labor and several other unions, alongside numerous reform-minded farm groups of the era. An insurgent response to the corporate monopolies, exploitation and harsh economic realities of the 1880s, the People’s Party wanted to exert greater control over an economic system rigged in the interests of a plutocratic elite. It called for federal loans to farmers, currency reform (including abandoning the wretched gold standard), support for free trade, and votes for women. With the backing of the Colored Farmers Alliance, it cut across racial lines, too. This was a genuine movement of the people against a corrupt elite.

Its 1892 Omaha Platform put the party’s case clearly:

‘We believe that the powers of government – in other words, of the people – should be expanded… as rapidly and as far as the good sense of an intelligent people and the teachings of experience shall justify, to the end that oppression, injustice and poverty shall eventually cease in the land.’

As Frank reminds us, it all went wrong for the People’s Party at the 1896 presidential election. Throwing its lot in with the Democrats, after they nominated a de facto Populist candidate in the shape of 36-year-old William Jennings Bryan, it not only lost the support of parts of its black constituency, who loathed the Southern Democrats’ racism; it then also witnessed Bryan lose to Republican William McKinley. From that point, writes Frank, ‘Populism fell mortally wounded’.

The People’s Party may have ultimately perished at the hands of America’s political duopoly, backed by a powerful business class. But, as Frank has it, the populist tradition persisted, because the political needs and desires it embodied persisted. People still wanted to exercise more control over their lives. They still wanted more democracy, more power over the economy.

Moreover, America’s labour unions, many of which had been involved in the Populist Party, continued to grow in the early decades of the 20th century, before positively flourishing as the Great Depression hit. This culminated in 1935 in the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which promptly set about recruiting America’s millions of unskilled workers.

Populism, unionised in the workplace, and fighting battles in the streets, was in the ascendancy during the 1930s. Frank even anoints the decade ‘Peak Populism’. ‘The people’, in all their everyday dignity, have rarely been as popular since. Frank writes of their hallowed representation in Hollywood movies, their eulogisation in popular and even modernist literature, their impact in congress, where they were breaking up the banks, and, above all, their presence in the White House, where Franklin D Roosevelt was in situ from 1932 onwards.

FDR, this scion of New York aristocracy, this product of Harvard, this seeming model of elitism, was, for Frank, a true man of the people. His speeches were peppered with populist rhetoric, as he slammed ‘financial and industrial groups’ and a ‘power-seeking minority’. And his actions were full of populist zeal, as he pushed through the New Deal. Yet, given FDR was a president who, after all, did side with employers in almost every industrial dispute, and who did reinforce racial segregation at certain points of his presidency, Frank is perhaps almost too gushing in his praise:

‘FDR bailed out farmers and homeowners, he protected unions, he pulled the teeth of the Wall Street wolves, he smashed oligopolies, he took America off the gold standard, and – although we don’t remember it today – he was roundly condemned by the nation’s respectables as the most dangerous demagogue of them all, a sort of one-man mob rule.’

Yet, as a means to reclaim a socially progressive legacy for populism, Frank’s presentation of the New Deal as an essentially populist achievement is impressively done.

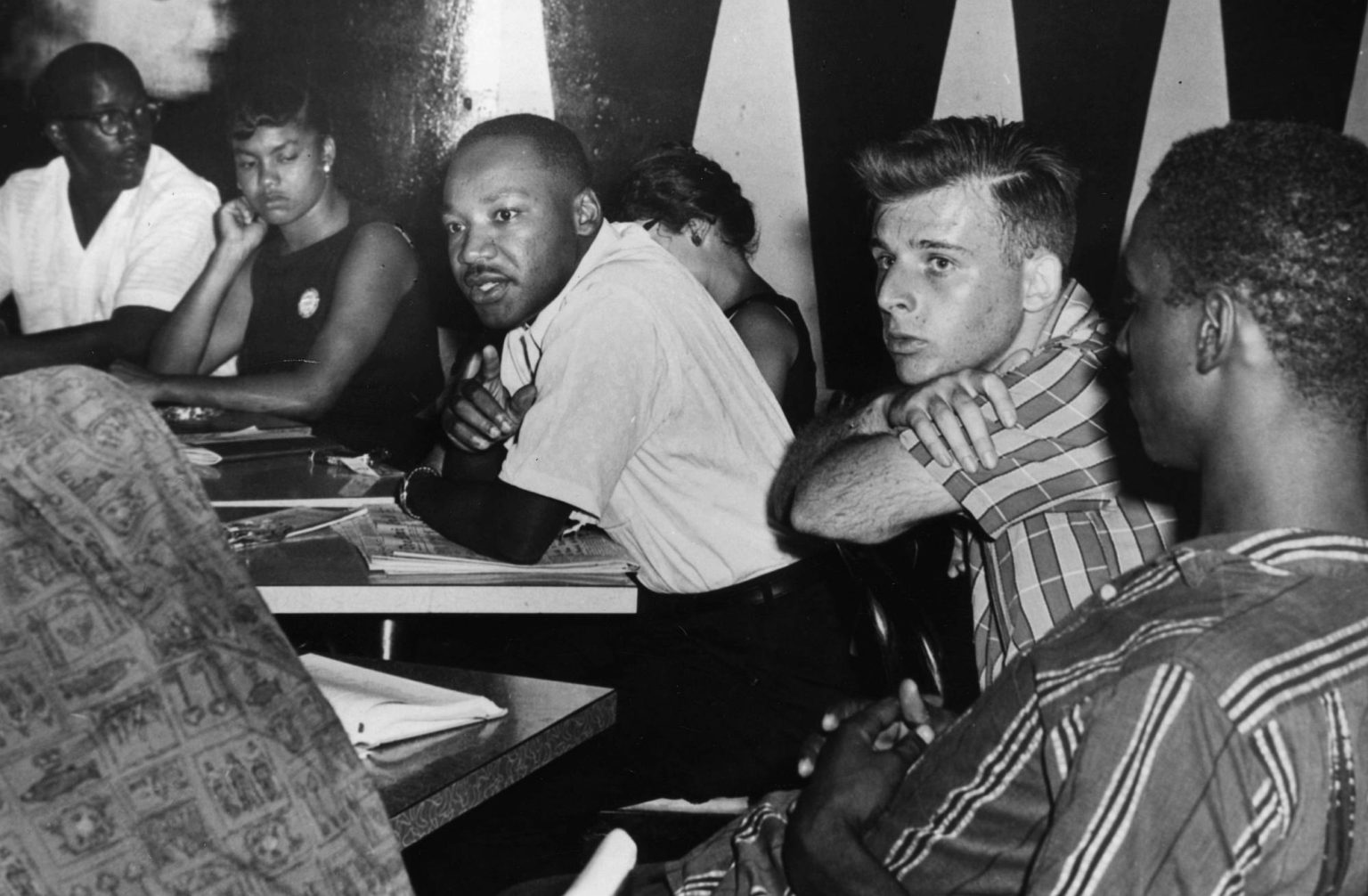

Perhaps more striking even than his populist appropriation of the New Deal-era US is his reframing of the civil-rights movement as a populist cause. As Frank tells it, the civil-rights movement was not only a demand for equal political rights for African-Americans. It was also premised on the recognition that blacks and whites had economic interests in common, too. In other words, in the struggle against political and business elites, they were, once again, ‘the people’.

Again, perhaps Frank overstates his case. But given the tendency among too many to view the civil-rights movement as a precursor to today’s elitist identity politics, it is a worthwhile overstatement.

Indeed, in a 1965 speech, Martin Luther King explictly argued that racial segregation was the historical product of the business-class’s attempt to defeat historical populism in the 1890s through dividing the labouring class on racial lines. ‘They saturated the thinking of the poor white masses with [white-supremacist thinking]’, said King, ‘thus clouding their minds to the real issue involved in the Populist movement’.

Frank quotes the democratic socialist author, Michael Harrington, writing in the New York Herald Tribune in March 1965: ‘King and others made it clear that they look, not simply to the vote, but to a new coalition of the black and white poor and unemployed and working people. They seek a new Populism.’ A populism, that is, based on fighting for jobs, for better wages, for improved working conditions. Or, as King put it in 1967, ‘Today Negroes want above all else to abolish poverty in their lives, and in the lives of the white poor’.

Perhaps this really was MLK’s dream. But, as The People, No makes clear, it was at this very moment, in the late 1960s, that the broader American left, from the Democrats to the vanguard of the counterculture, was to abandon the populist tradition to which it should have been heir.

The left’s anti-populist turn

As Frank shows, the basic elements of what we recognise now as anti-populism were evident from the 1890s onwards. And at its heart, as always, was a highbrow disdain for the capacity of the people to govern themselves. They were too uneducated, too emotional, too vengeful. For example, a 1936 anti-Roosevelt pamphlet, published by the capitalist-funded American Liberty League, ran as follows: ‘[Popular sovereignty] invests complete, direct power in those who are least endowed, least informed, have least, and thereby reduces government to the lowest common denominator.’

But, as Frank notes, the political identities of those propagating anti-populism did change. There were two key moments in this development, both during the mid-20th century. The first occurred in the 1950s, when anti-populism, hitherto a project of business interests concerned by ‘socialist’ or ‘commie’ troublemakers, ‘was taken up by a new elite, a liberal elite that was led by a handful of thinkers at prestigious universities’. Thinkers such as Daniel Bell, Seymour Martin Lipset and, above all, Richard Hofstadter, spoke on behalf less of capitalism now, than of ‘the vital center’, the emergent post-ideological governing class of experts and technocrats. They were the seemingly sensible voice of the emergent postwar liberal consensus. They ostensibly stood against extremes on both left and right, but, as shown by their response to McCarthyism, which they feared played on the darker prejudices of the rank and file, they positioned themselves essentially against the masses.

But perhaps more crucial still to the development of anti-populism was the second moment Frank identifies. This arrives with the expansion of universities during the 1960s, and the emergence of the student-dominated New Left. Initially, notes Frank, the New Left, with the 100,000-strong Students for a Democratic Society to the fore, was quasi-populist in spirit. This is palpable in the florid, countercultural excesses of the SDC’s 1962 Port Huron Statement, in which it declared that all humans were ‘infinitely precious and possessed of unfulfilled capacities for reason, freedom, and love’.

But as the 1960s progressed, the New Left’s populist sentiment waned, while its anti-populist impulse waxed. Every defeat, from the continuation of the Vietnam War to the assassination of MLK, was laid at the feet of white working-class America. Every failure to win support for its cause, writ large in the pro-Vietnam War Hard Hat Riot of 1970, was grasped as a failing of the people themselves. And here Frank makes an interesting observation: the class character of the New Left was emerging. For it was always essentially a movement of the would-be, or soon-to-be, bourgeoisie. Its response to political developments during the 1960s and early 1970s merely brought out its class position. After all, as Frank puts it, the New Left largely consisted of ‘young people in training for positions in the upper reaches of America’s middle-class society. They were a charming elite and even an alienated elite, but an elite nevertheless.’

Here, Frank is not as hard on the New Left as perhaps he ought to be. Too many of its leading figures turned against the working class with venom. They focused much of their theoretical energies from the 1960s onwards, channelling the excesses of the Frankfurt School, denigrating ‘mass man’, the ‘culture industry’ and the ‘authoritarian personality’. Worse still, they set about cementing the anti-populist myth of the essentially racist nature of ordinary American men and women. The likes of the Weatherman Underground, for instance, raged against ‘white skin privilege’, while others raged against working-class ‘Amerika’.

Still, although sympathetic to some elements of the New Left, Frank’s ultimate judgement is rightly severe:

‘The New Left succeeded in stripping the aura of nobility away from what the [Populists] called the “producing classes”, and in inventing an understanding of radicalism in which politics was no longer really about accomplishing public things for the common good. Instead… a satisfying sense of personal righteousness became the ultimate end of political action.’

This, I would argue, is a significant and damaging legacy of the New Left. It did not just abandon the working class and, with it, ‘the people’. It also turned them into a backward and bigoted stage army, in opposition to which ‘radicals’ were able to demonstrate their moral superiority. It is a legacy with which the left, lugging Hillary Clinton’s ‘basket of deplorables’ behind it, is still reckoning. Indeed, it is this legacy of ‘radical chic’ – of politics as self-aggrandising performance – that continues to give anti-populism its moral lustre. It says, ‘I am morally better than them’.

Populism lost

The People, No is a powerful defence of populism in the US context. But it is not a defence of what Frank sees as the ‘phoney populism’ of the Republican right.

Still, there is little doubting the success with which the Republicans have taken advantage of the Democrats’ withdrawal to the technocratic heights, and the broader left’s retreat into identity politics. It has allowed them to commandeer the rhetoric of populism. From Richard Nixon’s ‘silent majority’ (coined by Patrick Buchanan, who Frank enjoyably eviscerates), to Ronald Reagan’s appeal to ‘working men and women’, successive Republican politicians have played the ‘the people’ card. They have claimed to be for the common man, and against a corrupt elite. As Frank points out, the elite they rage against is not the coalescence of business and politicians of the older populism; rather, it is the governmental elite itself, committed as it is to ‘wasteful spending’ and ‘outrageous taxes’. But it is an elite nonetheless.

Frank is in no doubt as to just how phoney this populism has consistently proven to be. While Reagan may have appealed to the ‘people’ at election time, in power he ‘shifted the wealth of the world upwards in an unprecedented fashion’, deregulating banks, and ‘crushing the dreams of ordinary Americans’.

Nevertheless, ‘the right’s war on the establishment has been the inescapable political soundtrack of the past 40 years’, writes Frank. This is an important point. Too many accounts of populism today portray Donald Trump and his one-time svengali Steve Bannon as an unprecedented force in American politics. But in many ways, as Frank claims, much of Trump’s electoral pitch was ripped off from the Republicans’ long-term populist playbook. Reagan even promised ‘to make America great again’, way back in 1981. Frank goes so far as to call Trump’s populism ‘an assemblage of one-line clichés’, straight out of the populist playbook, but performed ‘with none of the old conviction’.

Yet Frank does what so many on the now firmly anti-populist left fail to do. He separates the phoney populism of the likes of Trump from the political truths of his populist message:

‘Just because the imbecile Trump denounced elites doesn’t mean those elites are a legitimate ruling class. Just because the hypocrite Trump pretended to care about deindustrialisation doesn’t mean deindustrialisation is of no concern. Just because the brute Trump mimicked the language of proletarian discontent doesn’t mean working people are “deplorables”.’

Yet, as we all know, Trump’s victory, like Brexit, did not prompt self-reflection among liberals and leftists, too long accustomed to denigrating working people as bigoted and racist. Instead, they doubled down on their anti-populism. They intensified their cliche-ridden attacks on Trump voters. And they rehearsed the slights with renewed vigour. ‘Scolding’, Frank calls it.

This amounts to something approaching a political tragedy. In continuing to turn on populism in general, liberals and especially self-styled leftists not only erect a barrier between themselves and the rest of society, consolidating people’s impression of them as, well, an elite. They also, as Frank has it, separate themselves from America’s very own radical tradition. Populism is not the problem here. Anti-populism is.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, by Thomas Frank, is published by Metropolitan Books. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.