The Scottish exams fiasco could have been easily avoided

Our myopic focus on the virus has thrown young people under the bus.

Because Scotland closed down schools as a way to tackle the virus, no exams were taken this year for the first time in history. Consequently, a system was set up to assess what the likely exam results would be, using past work by students and an assessment by their teachers. However, the educational authorities then made their own assessment of what the results should have been, based on previous schools records, and the outcome has been chaotic.

There is a statistical logic to what the Scottish government and education authorities did. They looked at the overall pass rate of schools from previous years and then looked at the 2020 grades given by teachers. Where there was a difference, they modified the results of certain students to fit with their school’s average.

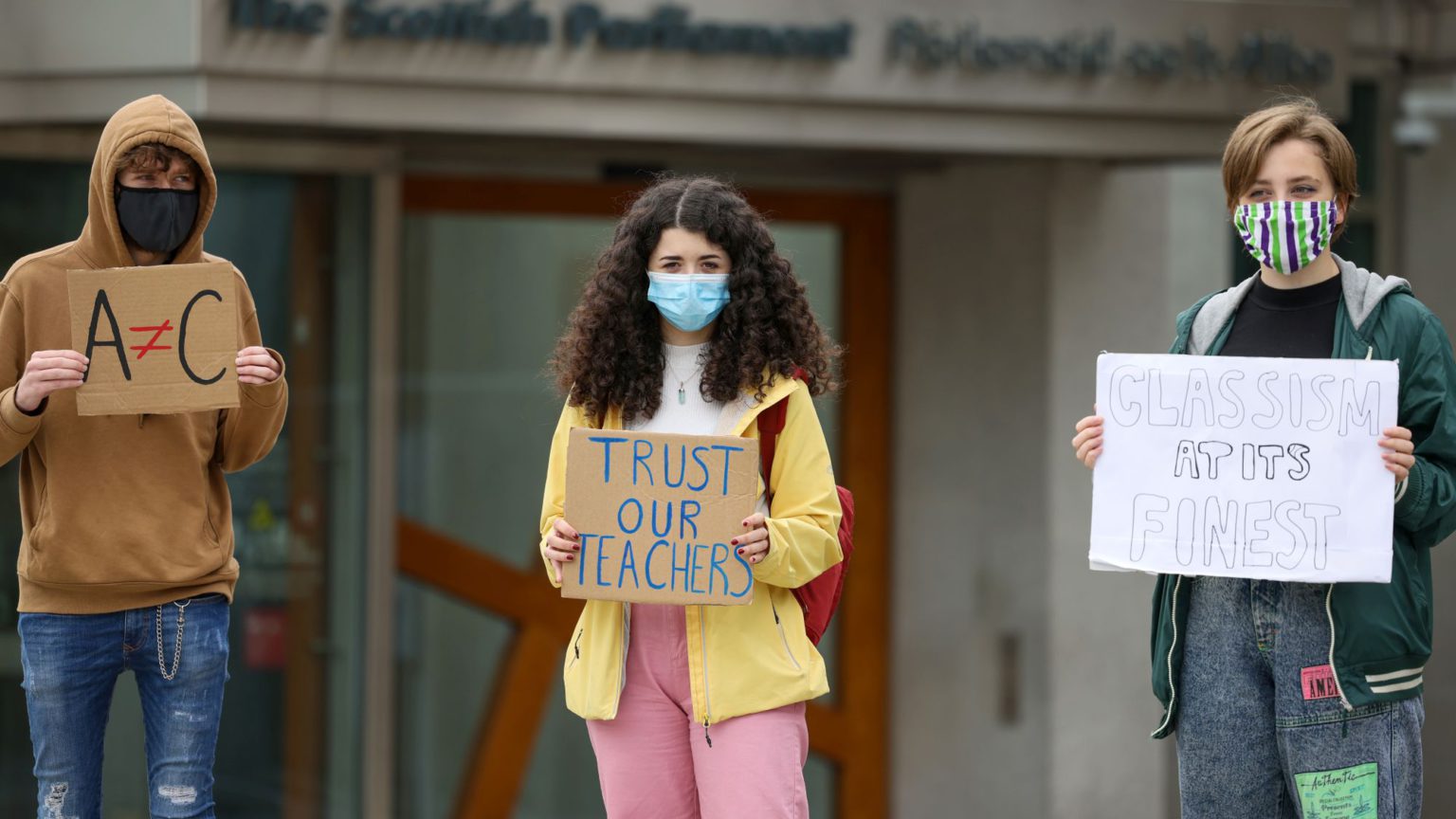

The outcome was that many children had their results downgraded, and children from working-class areas had their results lowered the most. For example, 15.2 per cent of children from the most deprived areas had their Higher results downgraded compared with 6.9 per cent of the wealthiest pupils.

The problem for the Scottish government is that its statistical model didn’t take into account the actual ability of individuals. So, for example, if a super smart working-class kid gets all As and his school, overall, has a poor pass rate, then it is possible that he will have had his grades deflated. This outcome has led to a serious backlash against a Scottish government that often goes under-scrutinised on its record in education.

Still, there was also a clear issue with grade inflation here across the board. The Scottish Qualification Authority (SQA) said that teacher estimates for Highers were 14 percentage points above last year’s results, and National 5s were 10.4 percentage points higher. While most teacher estimates were accepted, 124,564 results were dropped down a grade by the SQA.

A question that needs answering, but has received little attention so far, is why schools in working-class areas had such inflated grades overall, as given to them by their teachers, and why grades were inflated overall. While pupils and teachers were confronted with unique circumstances this year, rendered unable to complete their studies and sit exams, this all points to broader trends.

There has been a tendency towards grade inflation in education to the end of trying to solve social inequality. Questions about why so few working-class kids go to elite universities are raised annually, and universities have developed policies to allow young people from poorer areas to get into university on lower grades. The schools and teachers who inflated the grades of their working-class pupils this year are simply following the logic of this approach.

Part of this development relates to the more therapeutic nature of education these days, where the feelings, self-esteem and ‘wellbeing’ of students becomes increasingly important. Here ‘positive educational results’ become a logical mechanism for ensuring that working-class pupils, in particular, but pupils more generally, are rewarded in a way that is not entirely based on their academic ability.

The Scottish government’s original approach to these exam results was technocratic and did not take into account the actual abilities of individuals, and the outcry about this has resulted in a u-turn. Now, all results that were downgraded will be withdrawn and replaced by teachers’ original estimates, meaning that a significantly higher number of pupils will get good grades. This resolves the immediate political problem the government faces, but does nothing to address the wider problem of grade inflation. The likely outcome is that more students who lack the ability to achieve at university will be awarded a place.

As the professor of education Lindsay Paterson has argued, a better approach would have been to have external assessors look over the mock exams that pupils took – at least this way there would be a greater accuracy, leaving a smaller number of appeals cases to look over to ensure greater fairness for individuals.

All of this could have been avoided, of course, if education itself had been taken more seriously, if proper educational mechanisms had been put in place when schools closed, and if exams had been taken in some form. Unfortunately, once again, the myopic focus on the virus at the expense of every other area of life is proving to have unintended, if entirely predictable, consequences.

Stuart Waiton is a sociology and criminology lecturer at Abertay University in Dundee.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.