Long-read

Racialising the crisis in policing

Accusing UK police forces of systemic racism ignores the real source of the problems in policing today.

Police in the UK appear to be going out of their way to appear anti-racist these days. The Times reported recently that Scotland Yard was considering dropping the term ‘Islamist’ from its description of terror incidents motivated by radical Islam. Officers have been pictured ‘taking the knee’ in support of Black Lives Matter. And at the height of the lockdown, the Metropolitan Police effectively ignored the law in order to facilitate the BLM protests in Westminster.

Yet still police officers, particularly in the Met, cannot shake the allegation of racism. During the lockdown, officers were found to be 54 per cent more likely to fine black and ethnic-minority people for breaking the rules in London than whites. On 17 July, footage emerged of Marcus Coutain being arrested while a police officer kneeled on his neck – echoing how George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis. Coutain was later charged with possession of a knife in a public place. Last month, two officers were arrested after taking photographs in front of the bodies of two murdered black women. Such disregard for the dignity of the dead was met with justified outrage.

Yet it should come as no surprise that anti-racist posturing can exist alongside apparently racist behaviour within an organisation. This apparent contradiction is not contradictory at all. It reflects the fact that today’s ‘woke police’ still grapple with problems of prejudice. It would be surprising if any organisation in the world managed to rid itself completely of prejudiced individuals. But the fact remains that the persistence of racial prejudice is not the most significant problem facing the police today. It is strange that this even needs saying, but the vast majority of current police officers are not racists. They are civic-minded people who deserve our respect.

Sadly, this does require saying. Many commentators and members of the political class prefer to maintain the myth that little or nothing has changed between the police and the black community since the 1970s, rather than grapple with the specific challenges that the police and the justice system face. It seems that it is easier to blame endemic police prejudice rather than tackle the economic pressures and legal changes that are actually shaping policing today.

Racial policing

Part of the police’s embrace of anti-racism is a genuine attempt to make a break with the recent past.

In the mid- to late 20th century, policing practises reflected social anxiety about dramatic social change. This is captured by sociologist Stuart Hall in Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order, a book published in 1978, but still hailed as a definitive account of race relations and the police.

Policing the Crisis described the moral panic around ‘mugging’, which emerged in Britain in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Hall argued that this panic was part of a shift from a ‘consensual to a more coercive management of the class struggle by the capitalist state’. He observed that the postwar contract between the state and the working class, based on increasing welfare provision and social-democratic reform, had broken down, not least because the economic boom that had sustained it had given way to a massive economic slump. The result was an increase in working-class agitation during the 1960s and 1970s.

It was in these conditions that media and politicians began to portray a rise in street robbery as part of a deeper social malaise among working-class black men. The ensuing panic about ‘black muggers’ was used to justify a draconian response from the police and the courts. This panic culminated in the ‘Handsworth case’, in which a 16-year-old mugger was given a 20-year sentence in order to ‘send a message’. The sentence was well in excess of what would normally have been expected for a street robbery. Yet Hall felt it was too simplistic to argue that police forces and the judiciary were ‘inherently racist’. Rather, through the language of law and order, West Indian immigrants had become the medium for a broader assertion of control over the British working class.

And it is true: Britain’s police in the 1960s and 1970s became increasingly reliant on riot equipment and heavy-handed tactics to respond to relatively minor disturbances. This was not new, of course – the suppression of Irish Catholics in Dublin in the 18th and 19th centuries provided the template for the founding of the Metropolitan Police in 1829. But the shift in approach within the police in the 1970s still marked a significant move away from the postwar politics of consensus.

The increased militarisation of the police became publicly apparent during the Brixton riot of 1981. These riots followed ‘Operation Swamp 81’, a Metropolitan Police operation motivated by the panic over ‘mugging’ and violent crime. The operation led to the stopping and searching, and arrest, of hundreds of Brixton residents. It was mistakenly reported that the police had even allowed a young man to die while in police custody. This led to days of riots in which 279 police officers were injured. For Hall, the riots, in which an aggressive, empowered police force fought running battles with Brixton’s black community, were inseparable from the broader class conflict of the early 1980s.

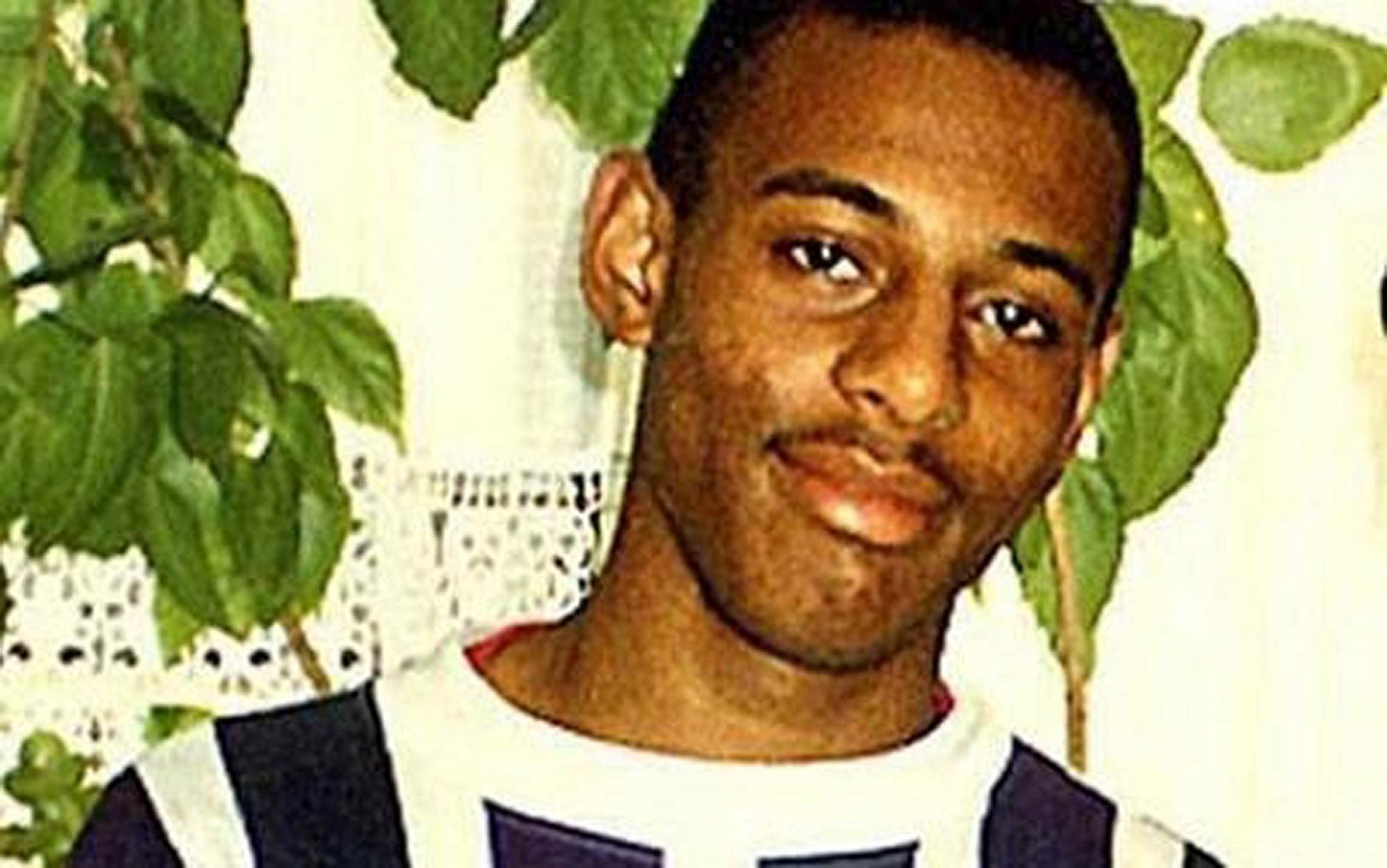

An apparent moment of reckoning for the police came in 1993, when Stephen Lawrence, a young black man, was murdered at a bus stop in Eltham, south London. The police subsequently bungled the investigation into Lawrence’s death, allowing its white perpetrators to get away with it. A judicial inquiry, led by Lord Justice Macpherson, soon followed, and the resulting report, published in 1999, catalogued the litany of mistakes that prevented Lawrence’s death from being properly investigated. The Macpherson report stated that the police investigation was ‘marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership’. This now famous conclusion appeared to find the police guilty of racially discriminating against the black community. But the ‘institutional racism’ identified by Macpherson was not expressed institutionally, in unjust laws or explicitly police policy. Instead, Macpherson argued, it was expressed in the unthinking assumptions held by individual police officers, which led them to treat black witnesses differently to white ones.

This definition of institutional racism was a departure from the institutional racism described in Hall’s analysis in Policing the Crisis. Hall’s argument was that the institution of the police had been weaponised in the course of class conflict, which disproportionately affected the black working class. Macpherson’s definition underplayed the role that the police played in any wider system of social control. Instead, institutional racism became a phenomenon that could be controlled by changing the attitudes and assumptions of individual police officers. This removed the focus on laws and policies that affected black and working-class people and refocused official energy on correcting individual attitudes among police officers. This important change in the meaning of ‘institutional racism’ sets the context for the fixation on racial disparities in policing.

‘Alternatives to explanation’

Today, the police exist in a post-Macpherson world. They have also adopted a definition of ‘institutional racism’ as indebted to woke writers like Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X Kendi as it is to Macpherson himself. For such writers, institutional racism describes any institution which, through the attitudes of the individuals involved, produces disparities in outcome between ethnic minorities and whites. It marks a significant departure from the institutional racism described by Hall, which considered how the police, as an institution, operated in a wider social and political context.

Issues surrounding policing are easily co-opted today into the culture war. The topic of knife crime is an obvious example. It has become the object of a bitter and interminable debate as a result of competing claims regarding race. The journalist Rod Liddle was labelled a ‘white nationalist’ in 2019 for saying that knife crime was driven by absentee fathers in the black community. In response, MP David Lammy described Liddle’s ongoing employment at The Sunday Times as a ‘disgrace’ – this despite Lammy having made the same point about absent fathers in 2012. The Guardian writer Afua Hirsch also wrote a piece in response to Liddle, arguing that the ‘black community’ was wrong to ‘self-blame’ and that knife crime was caused by the particular historical and social conditions affecting young black men.

What is rarely asked by commentators is how racialising these issues helps us to understand them. Where Hall understood race to be one in a complex web of factors influencing the police, too many today narrowly focus on racial disparity in the justice system and its supposed roots in individual prejudice. This can obscure rather than clarify the issues at stake.

Adolph Reed Jr, a left-wing academic from the University of Pennsylvania, has explored the limits of racialising social problems in the American context. He argues that racialised explanation of issues like police brutality are ‘at best shorthand characterisations of more complex, or at least discrete, actions taken by people in social contexts; at worst, and, alas, more often in our political moment, they’re invoked as alternatives to explanation’. Reed’s argument is that class, which was central to Hall’s analysis, is the often-ignored context for issues raised in the context of anti-racism. Reed cites research that suggests 95 per cent of police killings occurred in neighbourhoods with a median family income of less than $100,000 – that is to say, in poorer areas. What is more, according to Washington Post data, the states with the highest rates of police homicide per million of the population were among the whitest in the country.

For Reed, this racialising approach to political issues and social problems disrupts the possibility of solidarity among working-class communities. By seeing police violence ‘as mainly, if not exclusively, a black thing, we cut ourselves off from the only basis for forging a political alliance that could effectively challenge it’.

Reed’s critique is relevant to the UK. Presenting issues such as ‘stop and search’ as predominantly a matter of racial injustice underplays the impact that our dysfunctional drug laws have on the entire working class. Of course, race is a factor in stop and search. As I have argued before, there is at least some evidence that decisions to carry out these searches may be racially influenced. What is known, however, is that our drug laws encourage the draconian and arbitrary policing of the poor, irrespective of race. The London boroughs with some of the highest rates of stop and search are also the poorest: Westminster, Tower Hamlets, Lambeth, Newham, Southwark, Haringey. Focusing only on racial disparity in our discussion of stop and search risks missing deeper injustices connected to our arbitrary enforcement of drug laws.

For comparison, consider Scotland. There is no comparable racial disparity in the use of stop and search powers north of the border. It would be strange to imagine that Scottish police officers are inherently less racist than their London counterparts. But the class element of stop and search persists in Scotland. The targets of stop and search in Scotland tend to be ‘white teenage boys’ from ‘socially deprived areas’. Poor black kids in Newham and poor whites in Glasgow are both subject to the same arbitrary exercise of police power.

The focus on racial disparity in stop and search, and the treatment of it as a predominant injustice affecting the working class today, allows those in power to legitimise a wholly dysfunctional system of drug laws. In the Guardian, for example, Nazir Afzal, an ex-senior prosecutor, suggested that the disproportionate targeting of young black men by the police could be partly explained by the fact there has been only one BAME chief constable, and no BAME head of the Crown Prosecution Service. Likewise, the Lammy Review, published in 2017, asserted that a more ethnically diverse judiciary would lessen the sentences being handed down to black people convicted of drug offences. Increasing diversity is presented as the solution to policing ills.

It is remarkable how durable these arguments are. One study of crime, police and race relations from 1974 describes the urgent need to ‘recruit more coloured officers’ to ‘police coloured areas’ in order to improve relations with the local community. Today the police are more diverse than in 1974, but the problems remain. Perhaps that is because the flaws in the justice system are to be found in laws and policies, rather than the race of individual policemen and judges.

Consider deaths in police custody. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, deaths in police custody became a source of significant tension between the black community and the police, often with very good reason. In 1993, 40-year-old Joy Gardner died after police ‘trussed her up’ in shackles and a leather belt, and wound 13 feet of surgical tape round her head. The police responded to Gardner’s death by closing ranks, and the media intimated Gardner had been at fault. Tory MP Teresa Gorman even said Gardner was ‘bumming off social security’.

Gardner is just one of a long list of people who died at the hands of the police. In 1985, a group of officers raided Cherry Groce’s house in Brixton, looking for her son. Groce was shot dead in the course of the raid. Her shooting triggered the second Brixton riots.

It was always extremely difficult to obtain accurate information about such deaths. Custody suites were not as transparent as they are now. But, as is clear from the anecdotal reports in Hall’s and other studies from the 1970s and 1980s, young people taken into certain police stations simply expected to be badly hurt. Many deaths, like that of 21-year-old Colin Roach in 1983, were never sufficiently explained.

Today, it is imagined that there is a continuum between the militarised police force of the 1970s and 1980s and that of today. And there are legitimate arguments to suggest that some of the deaths in police custody in recent years were driven by racial stereotyping. The 2017 Angiolini Report into deaths in police custody found some evidence that stereotypes regarding the strength of black men had placed some of those who died at greater risk. But there is, thankfully, no solid evidence that black people are still dying as a result of racist violence from police officers in custody suites.

The introduction of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, and its accompanying codes of conduct, purported to make police custody suites more tightly controlled. While things do sometimes go wrong, it is now easier in the aftermath of incidents to understand what happened. What we see when we review the details of more recent incidents is that petty, low-level offending, involving drugs and alcohol, is pulling more vulnerable people into police custody. A lack of sufficient emergency mental-health services also means that police have to place people in custody who ought to be in hospital. Once these people are in custody, some of them are poorly managed.

The connection between dying in police custody and mental-health or drug problems is profound. The Independent Office for Police Conduct keeps detailed records of all deaths in police custody over recent years. In 2018/19, the IOPC recorded a total of 276 deaths, during or after police contact. These deaths include road-traffic accidents, later suicides, subsequent domestic disputes, and so on. Of these 276 deaths, 16 were in or following police custody. Of the 16 deaths in or following police custody, 10 people were identified as having ‘mental-health concerns’ and 13 were known to have a link to alcohol/or drugs. Fifteen people were white and one person was black. So, in 2018/19, white people significantly outnumbered black people in deaths in police custody.

In 2017/18, the number of deaths in or following police custody was 23. Sixteen people were reported to be white, six were black, and one was ethnically ‘other’. Of the 23, 11 had some force used against them by officers or by members of the public before their deaths. Six people were white and five people were black.

So in 2018, there is a clear racial disparity against black people. In 2019 the disparity was against white people. This is a snapshot, but it is also representative of the data across time.

The problem here is not race. It is something else. It is, I would suggest, dysfunctional drug laws, and poor mental-health provision. Reviewing the concluded inquests, what is remarkable about these cases of death in custody is that they all die in remarkably similar circumstances. Leroy Junior Medford, Adam Harris, Carl Maynard and Edson Da Costa all died after attempting to swallow packets of drugs and either suffocating or dying from profound intoxication. These are deaths that are entirely preventable with better adherence to police procedure. But what is worse is that none of these men would have been in custody had they not been arrested in connection with low-level drug offending.

Then consider the common factors in these deaths, which go beyond skin colour. Sean Rigg is often cited as an example of a racialised killing in police custody. In 2008, Rigg presented at Brixton police station with severe mental-health symptoms. He was restrained by officers in a way described as ‘entirely unnecessary’, and died in cardiac arrest later that day. Many commentators choose to see Rigg’s skin colour as the determining factor in his death. But consider, alongside Rigg’s, the 2015 death of Meirion James, a white man. He died in a ‘violent tussle’ with police outside his cell. CCTV showed James pulling clumps of hair out of his own head, which officers and custody staff members on duty were said to view as ‘childish’, rather than a sign of his deteriorating mental health. One officer could be heard on CCTV describing James as a ‘fucking idiot’. His requests to see a doctor were ignored, and he was violently bundled to the ground by several police officers after he lunged at them from his cell. He died of positional asphyxia.

Rigg and James had different colour skin, but they were both victims of the police’s incompetent and uncaring management of those with mental-health problems. The tragedy is that we rarely hear about deaths like this in police custody unless they fit a particular narrative about racial prejudice.

Years of grim reports of deaths in police custody reveal the uncaring culture of an under-resourced police force, rather than its racial animus. These deaths are symptoms of a police force that is performing its tasks with little support, low morale and, in some cases, institutionalised indifference. Of course, there are abundant committed and passionate police officers, but they are being forced to work in an institution whose role has been thoroughly debased in recent decades.

Policing people, ignoring crime

In recent years, the police have suffered significant funding cuts. According to the Institute for Government, central government grants have fallen by 30 per cent in real terms between 2010/11 and 2018/19. In 2011/12 alone, frontline officer numbers fell by 5.68 per cent across England and Wales – a loss of 6,800 officers.

Many commentators point to ‘police cuts’ as a cause of, say, rising knife crime. But few appreciate how underfunding changes the character of policing. With less time to investigate complex or multi-faceted offending, the police focus instead on easy-to-solve crimes. A 2013 report from the Independent Police Commission found that increased public demand for the police to maintain order made ‘effective, legitimate policing’ much harder to sustain.

Part of the problem, as the 2013 IPC report puts it, is the ‘growing public concern about anti-social behaviour’. In other words, there is an increased reliance on the law to solve what are often low-level, community problems. This reliance on the law to solve social problems, largely in working-class communities, was fostered by New Labour in the early 2000s, when it introduced a network of laws targeting low-level offending, including, most famously, Anti-Social Behaviour Orders (ASBOs). Between 1999 and 2013, 24,427 ASBOs were imposed on individuals across England and Wales, with many concentrated on the poorest areas of the nation, with Greater London, Greater Manchester, Merseyside and West Mercia criminal-justice areas issuing the highest number of orders. It is worth reiterating that it is precisely this heavy-handed policing of low-level offending and anti-social behaviour that leads vulnerable people to be placed in police custody in the first place.

At the same time as the focus on bad behaviour and low-level offending has increased, so the number of serious crimes solved has fallen dramatically. Hence, the number of people charged with an offence following an arrest has decreased year on year since 2015. For example, in 2015/2016, the sanction detection rate for murder (that is, cases that count as solved) stood at 93 per cent. By 2017/18, it had fallen to 66 per cent. In other words, a third of all murders in London went unsolved. Given that young black men are more likely to be both the victims and the perpetrators of violent crime in London, this is likely to represent a large number of young black male murders that will never be solved.

Race and justice

Since 2015, I have worked on reviewing murder convictions, with the assistance of law students. The majority of these convictions have involved young black men. You cannot do this work for long without seeing that there remain aspects of the justice system that encourage racist thinking. For example, the Met’s database of suspected gang members in London, known as the Gangs Matrix, actively encourages black friendships to be recast as sinister criminal networks; and joint-enterprise law often criminalises huge groups of young black men for peripheral involvement in violence, sometimes on the basis of nothing more than receiving a phone call or appearing in a music video.

Moreover, as the Lammy Review discovered, when young black men face trial, they are more likely to disengage from their legal team, on the basis that they believe their own lawyers to be ‘part of the system’ – a system they are told, time and again by racialising critics, that is supposedly geared against them.

There are real problems, then, that persist with regards to race and the justice system. But to address these problems, we will need to confront complex realities that cannot be reduced to simple narratives of institutional or ‘systemic’ racism – realities that involve real black, working-class men who possess agency and make decisions for themselves. These men are not always easy to portray as victims. And they make complex moral decisions that are not entirely governed by their economic disadvantage.

Consider the fact that 252 people were killed with knives during 2018. Now, it is very clear that many of these crimes were linked to county-lines drug-dealing. The Lammy Review identified how a lack of police resources meant that officers were struggling to disrupt the more senior members of the drug gangs, who were pulling young men into serious violence. So these murders can be blamed, in part, on the under-policing of the criminal networks that recruit young men into violent conflicts over territory.

But there was another significant category of ‘killing with knives’. This involved minor social disputes that escalated into murderous violence, with no clear explanation as to why. Take the killing of Harry Uzoka. He was a promising model murdered by his best friend in an argument over a girl. Uzoka was not involved in drugs. And neither he nor his killer were economically deprived. Or take Malcolm Mide-Madariola, who was knifed by Tammuz Brown, after he stood up for a friend with whom Brown had a ‘trivial’ dispute. Or take the mass brawl in a children’s play area in Camberwell, prompted by an argument over a belt, but which ended with a 15-year-old boy being ‘disembowelled’.

We have to be able to discuss honestly why young men and boys are turning to nihilistic levels of violence in the face of trivial social disagreements. Appealing to poverty or the closure of youth clubs is simply not enough. There is a cultural problem driving these killings, and it has nothing to do with race. These killings appear to be motivated by a willingness to defend one’s self-esteem, or self-image, through murderous violence. This is profoundly worrying. It illustrates a nihilistic level of narcissism that appears to be driving at least some of the murders in our inner cities.

But too many of today’s pundits and politicians refuse to accept the realities of crime and young working-class black men. They seem unable to accept that they no longer face the same problems with the police as their parents and grandparents did 30 years ago. This will not do. We need to move the conversation on from the caricature of a racist police force that has persisted since the 1970s.

Conclusion – back in Brixton

The racial prejudice of individual officers is far from the most pressing problem facing the police today. Far more significant are the legal and economic changes that have led the police to concentrate on low-level misbehaviour while ignoring serious crime. We should understand the racial disparity that flows from these changes, with the police focusing on low-level offending in poor, working-class areas. Understanding this is key to fixing some of the persistent problems of law and order that we face today.

While it is wrong to generalise from single events, one recent news story captures well the problem of policing today. In June, there was an illegal rave on the Angell Town Estate in Brixton, a stone’s throw from the site of the 1981 riot. During the day, a dispersal order had been put in place to prevent a rave happening in the middle of the estate. Under the conditions of the order, the police were to break up the rave, and arrest people who failed to comply. Despite this, the police allowed the rave to proceed, despite complaints from residents. In the evening, it turned violent.

Footage on social media showed several police vehicles being smashed and officers being chased. Another video also appeared to show two men being attacked with a knife. Officers ran from the scene, presumably leaving large quantities of equipment behind.

It is worth taking a moment to consider how this looked to the working-class residents of that Brixton estate, some of whom may even have rioted against police brutality in 1981. If the Handsworth mugging captured the moral panic of the 1970s, then the police turning and fleeing from the residents of the Angell Town Estate captures something of the nature of policing in 2020. The police tweet about Black Lives Matter protests, but will run away from their obligation to protect predominantly black, working-class estates. They label an estate ‘red’ on the Gangs Matrix, while being unable to protect its residents. This is not the fault of officers on the street. Nor is it due to the few who may still harbour racist prejudices. Rather, it is the product of a police force that is legally driven and financially pressured to over-police petty conduct and under-police serious crime. It is this dynamic that lies at the heart of our ‘anti-racist’ police force today.

Luke Gittos is a spiked columnist and author. His latest book, Human Rights – Illusory Freedom: Why We Should Repeal the Human Rights Act, is published by Zero Books. Order it here.

All pictures by: Getty Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.