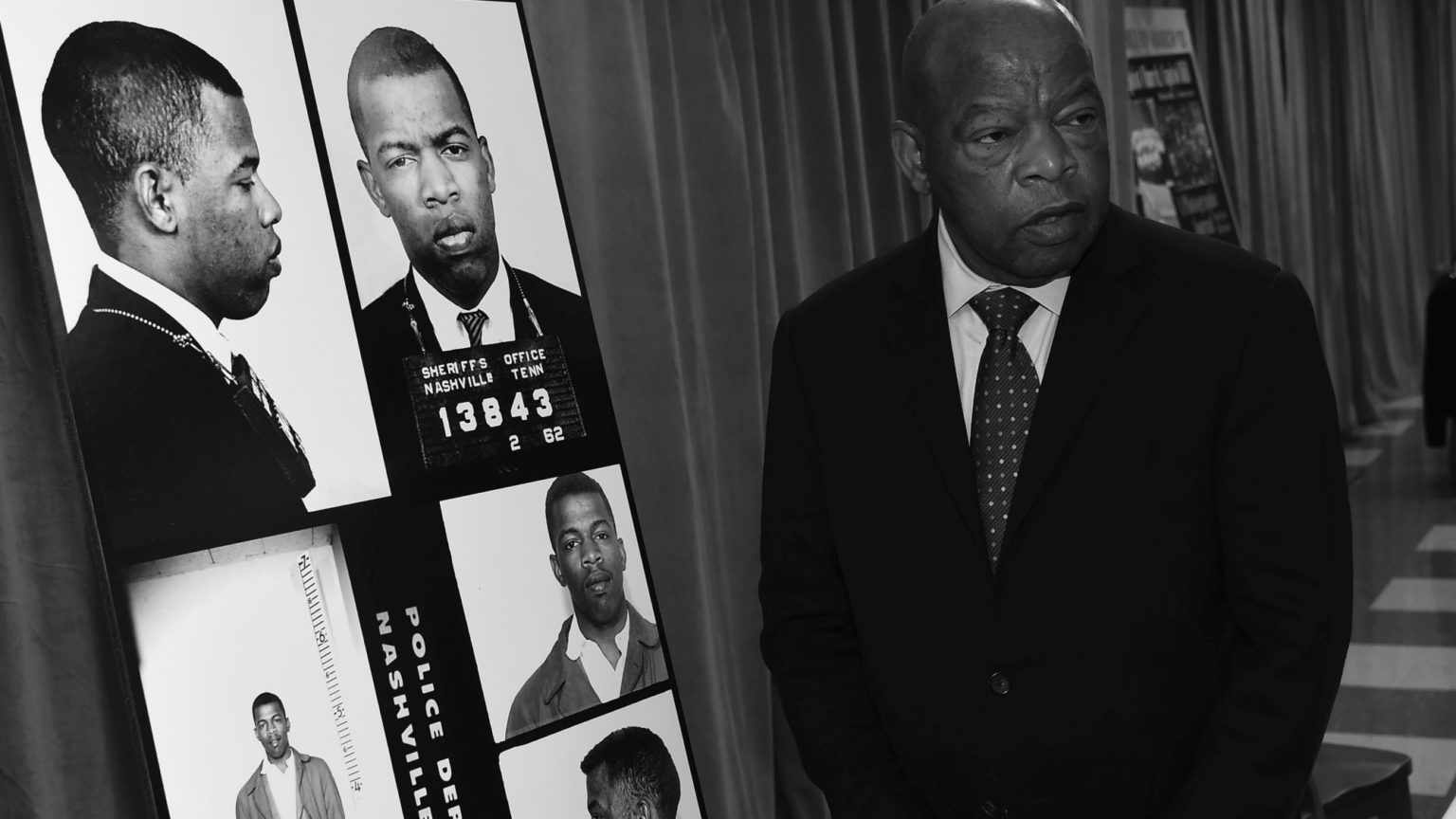

John Lewis: ‘good trouble’

The civil-rights giant will be remembered for his incredible courage and hopefulness.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In 1965, a 25-year-old old black man named John Lewis, wearing a white shirt and tie, marched quietly at the front of a long column of black people marching for the right to register to vote. Burying his hands in the pockets of a trench coat, he walked coolly toward a phalanx of Alabama state troopers in helmets and gas masks and clutching nightsticks. He stopped a few feet away from the line of troopers. The other marchers stopped, too.

Using a megaphone, the head trooper ordered the crowd standing on the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma, Alabama, who had been moved to protest by the police killing of a black man, Jimmie Lee Jackson, to disperse. Lewis stood stock still and, with the other marchers, completely silent. The troopers attacked. One of them shoved a truncheon into Lewis’s gut, pushing him backward into the line of marchers, who began to trip over one another. Tear-gas canisters exploded overhead. The marchers, most of them women, screamed as they fled the swinging clubs of the troopers. Lewis took a club to the head, sustaining a serious skull fracture that nearly killed him.

Lewis – who died on Friday aged 80 – also spoke at the legendary 1963 March on Washington. He was the youngest and last surviving member of the ‘Big Six’, a group of prominent civil-rights leaders that included James Farmer, Martin Luther King Jr, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young and A Philip Randolph. John Lewis, as much as any of the others, epitomised the incredible bravery and hope of that generation of civil-rights activists.

As a young boy in Pike County, Alabama, in the 1940s, Lewis attended a one-room schoolhouse that had no running water, no well and a single pot-bellied stove for warmth. The son of sharecroppers who grew peanuts and cotton for a white landowner, Lewis dreamed of being a preacher. As he recalled in his autobiography, he practiced his orations on the family’s chickens. He loved school and managed to get a place at the American Baptist Theological Seminary (ABT) in Nashville, Tennessee. College was the first time in Lewis’s life that he had a bed of his own. At home he had always shared a bed with one or two of his brothers.

As Lewis later recalled: ‘When I was growing up, and asked my mother and my father, my grandparents, and my great-grandparents about the signs and about segregation, they would always say, “Don’t get in trouble; don’t get in the way”. But I met Rosa Parks when I was 17, and the next year, at the age of 18, I met Dr King. And those two individuals inspired me to get into what I call “good trouble”. And I’ve been getting into trouble ever since.’

In his first year of college, Lewis hatched a plan to desegregate Troy State University. He wrote to Martin Luther King Jr about it. King’s group sent Lewis bus fare to Montgomery so they could meet. King – not for the last time – attempted to cool the ardour of the young man by reminding him of the potential repercussions on his family. And, not for the last time, Lewis took the advice of the civil-rights hero.

King had inspired him. In the autumn of 1959, inspired by the creed of non-violence espoused by MLK, Lewis and other blacks students formed the Nashville Student Movement and set up a plan to integrate lunch counters in the city. He later went on to co-form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In a long career that spanned the most memorable civil-rights struggles in the South, Lewis was arrested some 40 times, and frequently suffered segregationist violence.

In 1961, Lewis was attacked at a Greyhound bus station in Rock Hill, South Carolina for entering a ‘whites-only’ waiting room, as he travelled through the South to protest against segregated transportation. ‘I remember him laying there, and it was blood on the ground and somebody done called the police’, remembered the late Elwin Wilson, a former member of the Ku Klux Klan who participated in the assault on Lewis and later apologised and repented.

When Lewis was just 23 years old, he spoke in front of an audience of 250,000 people at the March on Washington, under the huge, brooding figure of the Great Emancipator. Historical controversy surrounds the events of that day (1). The fiery speech he had prepared was met with consternation among some of the civil-rights leaders, including MLK, who said that certain passages ‘don’t sound like you’. Lewis duly changed the offending sections.

This included a statement calling the proposed legislation that would become the 1964 Civil Rights Act ‘too little and too late’, and a threat to ‘burn Jim Crow to the ground – non-violently’. Still, the historian Adam Fairclough has called the controversy a ‘storm in a teacup’, noting that, ‘In such a context… it made no sense to denounce the proposed Civil Rights Bill’ or to appear to threaten the South (2).

Lewis began working in government during Jimmy Carter’s administration, on anti-poverty policy, and was elected to be a member of Atlanta’s city council in his adoptive state of Georgia. In 1986, he was elected to a seat in the US House of Representatives, where he served until his death. He opposed the Iraq War and high levels of defence spending. He was supportive of President Obama, who hugged him at his inauguration and told him he was president only because of the sacrifices Lewis had made.

Lewis should be remembered for his incredible courage, his inspirational hopefulness and his love – not just of his people but all people, of the entire country. When Elwin Wilson, the Klan member who had beaten him in 1961, died in 2013, Lewis magnanimously wrote: ‘Elwin Wilson shows us that people can change, and when they put down the mechanisms of division and separation to pick up the tools of reconciliation, they can help build a greater sense of community in our society.’

The last words here should be Lewis’s. In an interview from 2017, he said:

‘I tell young people, especially young children, when someone says to me “nothing has changed”, I feel like saying “come and walk in my shoes. I will show you change”…

‘[W]e cannot let that sense of hope die, and we cannot let it be beaten down, or let it wither on this unbelievable American vine. I tell young children – and adults – that we must not get lost in a sea of despair. We have to be hopeful and be optimistic. Be bold, be brave, be courageous, and just get up and push and pull…

‘I say when you see something that’s not right, not fair, not just, you cannot afford to be silent. You have to do something. Wherever you find yourself, speak up, speak out, and find a way to get in the way, to get in what I call “good trouble, necessary trouble”.’

Kevin Yuill teaches American studies at the University of Sunderland.

(1) See ‘Civil Rights and the Lincoln Memorial: The Censored Speeches of Robert R Moton (1922) and John Lewis (1963)’, by Adam Fairclough, Journal of Negro History, Vol 82, No4 (Autumn, 1997), pp408-416.

(2) Ibid, p415.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.