Brave New World: the importance of thinking freely

Huxley shows us that failing to think for ourselves leaves us open to domination.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Aldous Huxley worried about love. In an essay written in 1943, which formed part of his collection Do What You Will, he discussed a rebellion by young people of the 20th century against the sexual morality of the Victorian era. The problem was that lots of young people were having sex. They were having sex in a way that seemed completely unmoored from what was deemed acceptable at the end of the 19th century.

Huxley was not a prude. In his later life he expressed what was close to revulsion with the Victorian nuclear family. But he also expressed concern that something important could be lost with this new sexual revolution. He wrote that a ‘sordid and ignoble realism offers no resistance to the sexual impulse, which now spends itself purposelessly, without producing love, or even, in the long-run, amusement’. If Huxley was sceptical of the nuclear family, he did not see much potential in unrelenting promiscuity either. Young people in the 1940s, he said, no longer ‘love with a large L’.

Huxley’s Brave New World, written 10 years before the essay quoted above, is a novel in which love and relationships have ceased to mean anything. It depicts a world in which reproduction is tightly controlled by growing babies in mass hatcheries. In this world, ‘Everyone belongs to everyone else’. Sexual promiscuity is seen as a social duty. Huxley was a member of the Bloomsbury set, a group for writers who delighted in attacking and inverting Victorian things like traditional marriage. But the promiscuity of the New World citizens is empty. Sex has been reduced to the temporary satiation of physical impulses. This is why even children in Brave New World have to engage in ‘erotic play’.

The language of Brave New World reflects this loss of meaning. Words which once described familial bonds – ‘mother’, ‘father’, ‘birth’ – are all remembered as expletives, spoken by previous generations of humans. When our protagonist Bernard Marx sees a ‘savage’ breastfeeding a child, he is ‘surprised by the intimacy’ of the relationship. It is this intimacy that has been done away with in the New World, along with the terms that once described intimate relationships. Promiscuity is the only way to satiate one’s own urges, without the emotional risk of commitment.

It is not the only aspect of social life which has been rendered meaningless. Bernard Marx meets John, a ‘savage’ from ‘the reservation’, a small area of the world that has not been subject to social controls. When John returns to the New Word, he brings with him his knowledge of Shakespeare. He quotes Juliet’s speech in which she implores her mother to allow her to die, and be buried alongside her cousin Tybalt, rather than marry someone she does not love.

But the strength of Juliet’s feeling is incomprehensible to the citizens of the New World, as is her sadness at death. When Linda, John’s mother, is portrayed dying on a ward, drugged and oblivious, her carers politely question why John would feel any loss. The elderly in the New World are executed at 60 years of age, when they have allegedly exhausted their social value. Love and death both require us to make choices and take risks with our emotions. And risks are not acceptable in a world as tightly controlled as Huxley’s.

Huxley’s book is often described as prescient for its remarks on reproductive technology. But it was arguably prescient in a different and more powerful way. Huxley wrote Brave New World in 1931. This was more than three decades before Hannah Arendt, the German philosopher, would attend the trial of Adolph Eichmann and describe the ‘banality’ of his evil. Arendt controversially claimed that Eichmann was not evil because he chose evil, but because he did not choose at all. He did not think and make judgments about what he was doing. Instead he blindly followed the legal order of the Nazi regime. Eichmann’s evil, his moral failure, was in his failure to think.

The banality of evil is the very foundation of life in the Brave New World. The only reason the citizens of the New World are content with their lives is because they are unthinking. We, as the readers, are forced to question why this regimented, eugenic society could be described as evil. Huxley is asking us: ‘What is the problem here?’ He sharpens this question through one important addition to the New World. One which is absent from Oceania in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and the dystopias of HG Wells. The magic ingredient in Huxley’s dystopia is happiness.

The characters of Huxley’s book are happy. When Bernard Marx asks Lenina, ‘Don’t you wish you were free?’, she responds, ‘I don’t know what you mean. I am free. Free to have the most wonderful time. Everybody’s happy nowadays.’ Lenina’s understanding of freedom is a freedom from discontent. The happiness that is achieved in the New World is an unthinking bliss.

The only character in the book who has ‘chosen’ anything about their happiness is the Controller, Mustapha Mond – a member of the New World elite, who reveals that he was offered the opportunity to travel to place himself in exile. Mond reveals that he chose to stay in the New World and ‘serve happiness’. He is sure to clarify: ‘other peoples’ happiness, not my own.’ Mond’s phrasing illustrates something important about the happiness of the New World. ‘Serving happiness’ does not make oneself happy. New World happiness is merely a system of social control: something that can only be ‘served’, rather than truly felt.

Huxley’s book is famed for its portrayal of the New World babies, who are prepared for their preordained life through psychological conditioning. They are barraged with repeated words and phrases throughout their sleep to prepare them for their designated career path. But what people forget about Huxley’s world is that this conditioning does not end in the hatchery. The adults of the New World continue to condition one another through their self-censorship and linguistic correction.

Huxley’s New World state recognises that people’s inner life can be revolutionary and dangerous. To control language is to control the medium for thought, and therefore to put off rebellion. Huxley’s language-policing New World citizens echoes John Stuart Mill — they remind us that the most powerful form of censorship and social control can be found in the ‘tyranny of custom’. Huxley’s New World state is powerful, but the New World order is not the all-seeing totalitarianism of Big Brother – it is the unthinking compliance of its citizens and their relentless mutual censorship that allows the Brave New World to function.

Arendt, writing in The Human Condition, conceives the intimate sphere as the realm of ‘radical subjectivity’. It is the space in which we are free to think and experiment with our thoughts without the need to present them in the public sphere. People are most vulnerable to domination when their inner life and their ability to experiment with their own thoughts, to think on their own terms and in their own words, has been exhausted.

New World citizens are in exactly this position. At the reservation, John the savage ‘had suffered because they had shut him out of communal activity. Now in London he was suffering because he could never escape communal activities – he could never be quietly alone.’

Huxley’s Brave New World is an exploration of the kind of happiness that arises from a state of unthinking. It is a book about what happens when we cease to have any inner life to speak of; when the line between our ‘radical subjectivity’ and our obligations to public life break down. In this sense, Huxley’s observations on the radicalism of our inner life are more prescient than his remarks about technology or reproduction.

We are all constantly in danger of the domination that arises from failing to think for ourselves. Huxley teaches us that human beings are only truly happy with the truth, and when we think for ourselves. There is no happiness in the state of ‘serving happiness’ – that is, in unthinking conformity.

Luke Gittos is a spiked columnist and author. His latest book Human Rights – Illusory Freedom: Why We Should Repeal the Human Rights Act, is published by Zero Books. Order it here.

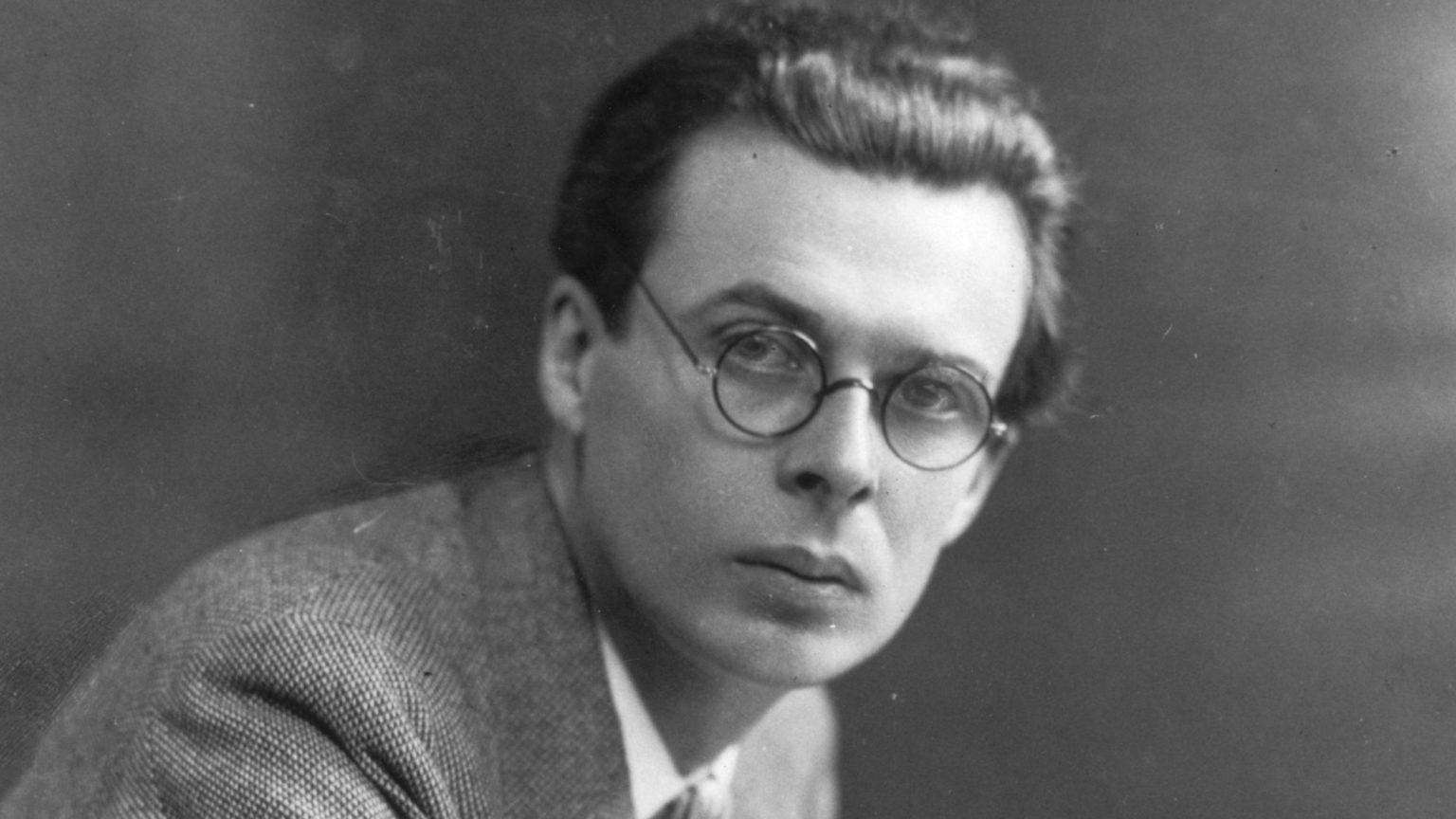

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.