Long-read

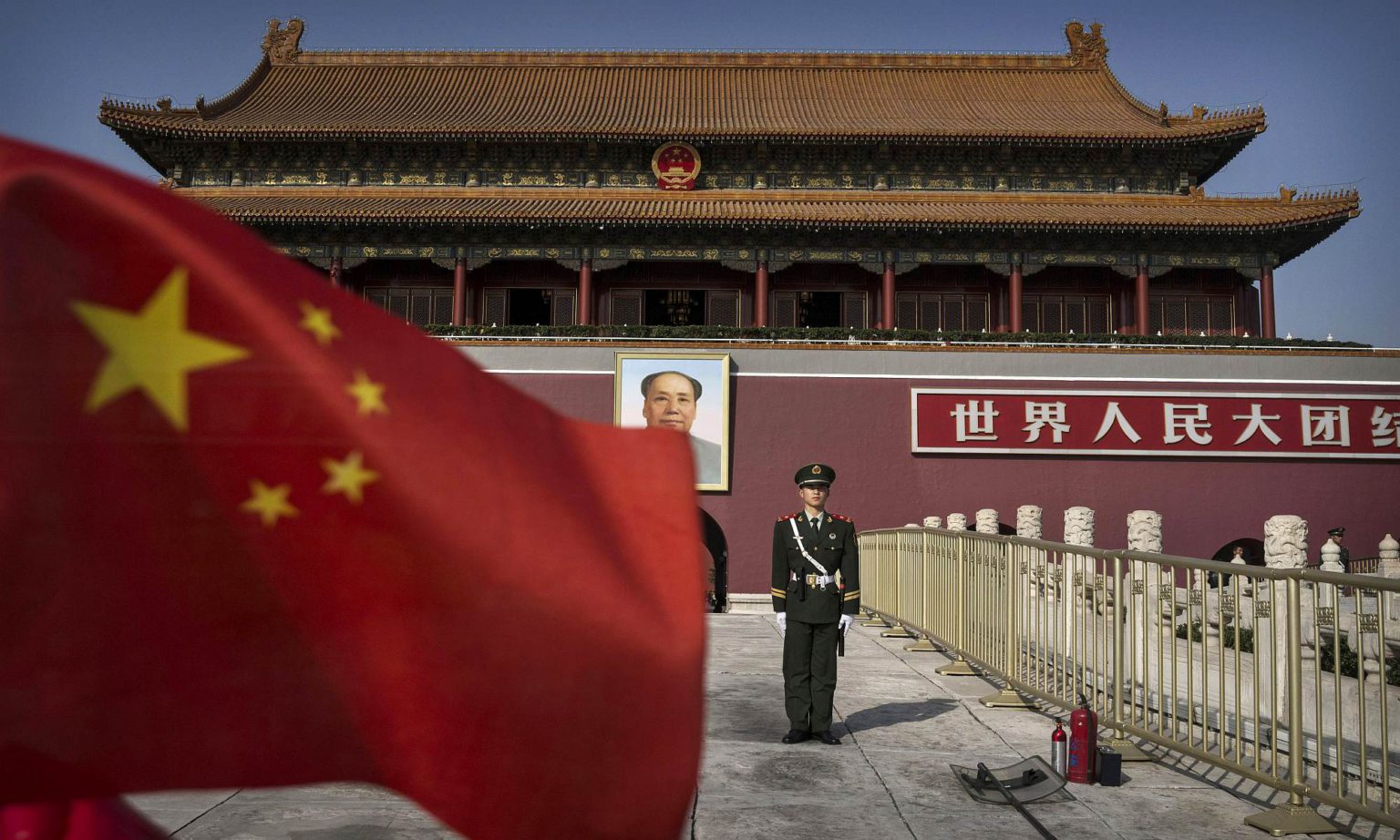

Why the West must stop bashing China

Western governments' attempt to scapegoat China for their own shambolic response to Covid-19 will have terrible consequences.

‘We’re in 1938’, claimed Steve Bannon, former chief strategist to President Donald Trump. He was comparing the proposed national-security laws being imposed on Hong Kong by the Chinese government to Germany’s invasions of Austria and Czechoslovakia in the run-up to the Second World War. Bannon went on to warn about China: ‘If we blink, we’re heading on a path to war, to a kinetic [military] war, if we don’t stop it right now…. This is not a cold war. This is a hot information and economic war, and we’re sliding rapidly. We are inexorably going to be drawn into an armed conflict if we don’t stop this now.’

Bannon’s perspective exemplifies the toughening anti-Chinese stance that has consolidated itself since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Chinese government is accused of being too slow to recognise the threat of the coronavirus, and to have delayed alerting the rest of the world. These failings are put forward as confirmation that the Chinese state represents a political and strategic threat to the US, and to the Western world more widely. Such China-blaming spread quickly across most capitals of the advanced industrialised countries, from Washington to Canberra.

The problems many Western governments have had in acquiring enough medical and personal protective equipment, and certain pharmaceutical products, have been turned into a stick with which to beat China. Rather than waking up Western governments to the dire state of their internal manufacturing capabilities, their pandemic failings have been blamed on a precarious over-dependence on Chinese production from which the West needs to free itself. This accentuated belief in the threat from China could turn into the most dangerous consequence of the impact of Covid-19.

An authoritarian one-party state

It is entirely legitimate to condemn coercive actions carried out by China’s autocratic one-party government. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has an extensive record of authoritarian behaviours denying its own people basic freedoms, often with brutal suppression.

Freedom of assembly and freedom of speech are severely restricted. Workers, prohibited from establishing independent unions, are required instead to join only the CCP-controlled All-China Federation of Trade Unions. Nevertheless, every month hundreds of protests are organised by workers over wage arrears and working conditions, sometimes leading to police attacks and the imprisonment of activists.

The CCP has persecuted the Uighur minority in the Xinjiang region, consistently denied the rights of Tibetans, and sanctioned attempts by the local authorities to break up the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, where it has now decided to impose new security laws. And across China, the CCP has clamped down on social media and deployed surveillance technology to control internal dissent.

Even though coercive actions by state forces are hardly unknown within Western democracies, that is no reason to ignore or tolerate them when they take place in China. The denial of people’s rights should be challenged wherever it happens around the world. Governments in other countries, as well as citizens, could be clear that the CCP-run Chinese government should be accountable for its actions to its own people.

Making a bad situation much worse

But what is illegitimate and should be challenged is other governments’ interference in China’s own affairs. Just as problems in the US are for American people to resolve, and problems within Britain are for British people to sort out, the same applies with regard to China’s national sovereignty.

Repression against Chinese people, the same as the repression meted out by authoritarian regimes anywhere, will not be resolved by other governments or international bodies stepping in with economic or other weaponry. External state intervention in a country’s affairs is a repudiation of democracy at the higher nation-state level. Undermining national self-determination through trying to replace one governmental regime with another one always denies the local people the right to decide their own futures. Westerners who tolerate such state stratagems, even with the best of intentions, are undermining the struggle for democracy and progress everywhere.

Yet such Western governmental confrontation is now being advocated by the China-bashers. Legitimate condemnations of measures taken by the Beijing regime have turned into arguments for the Western authorities to take action against China as a national entity. The recent heightened hostility towards China has escalated into overt geopolitical contestation. Particular instances of atrocious CCP practices are now used to show that China has become an existential threat to the Western mode of life. The US and most other Western governments are increasingly discussing China as a strategic opponent.

In America, the Committee on the Present Danger: China, which Bannon helped set up last year, describes China as representing ‘an existential and ideological threat to the US and to the idea of freedom’. The relaunched committee is campaigning for an American consensus to defeat this perceived threat. In fact, the mainstream consensus on this has already gone a long way. Across the American political class, moves to isolate and punish China have become the accepted bipartisan stance. Trump and Joe Biden, Trump’s presidential rival in this year’s election, have already made China a major campaign issue, accusing each other of weakness in confronting America’s new No1 foe.

In Britain, senior Conservatives have established a similar campaigning body, the China Research Group, modelled on the European Research Group that campaigned for Brexit. The stated purpose is to work out how to protect Britain from the Chinese government’s ‘aggressive economic policies’, which are said to be aimed at ‘dominating’ the West and ‘reshaping’ the world in a way that ‘suits autocracy’.

According to Tom Tugendhat, one of the co-founders of this campaigning group and chair of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, ‘the cost of doing business with autocratic regimes is that you don’t just import their technology, you also import their values and make yourself dependent on their politics’. Somehow having business connections to China makes other countries ‘dependent’ on CCP ‘values’ and ‘politics’. While this exposes the lack of confidence some Western politicians have in their own values and their own politics, the message Tugendhat proclaimed is serious: ‘the virus has clarified the choice’ – it’s the West versus China.

Downing Street officials have already said that China faces a ‘reckoning’ over its handling of the outbreak and risks becoming a ‘pariah state’. The government is expected soon to announce tougher constraints, maybe even a ban, on the deployment of 5G telecommunications equipment from the Chinese supplier, Huawei. It seems the so-called ‘golden era’ in Sino-British relations, launched by David Cameron and George Osborne only five years ago, is over. As in the US, opposition politicians from the Labour Party and elsewhere are aligning with the tougher anti-China standpoint.

China is now increasingly seen as an existential threat by openly globalist governments in Western and Northern Europe. According to one senior European Union (EU) diplomat, the starting point for European policy towards China was, until quite recently, an eagerness to engage, but it now begins with pushing back.

NATO has also joined in, urging ‘like-minded countries’ to join the transatlantic military alliance and stand up to China’s ‘bullying and coercion’ in world affairs. As well as ‘heating up the race for economic and technological supremacy’, Jens Stoltenberg, NATO’s secretary-general, identifies China’s rise as ‘multiplying the threats to open societies and individual freedoms, and increasing the competition over our values and our way of life’. The focus is no longer on technology and economics, as it was a few years ago. It is now on China’s threat to the Western ‘way of life’.

In Australia, too, one of the countries NATO seeks to work with more closely, the government has become increasingly outspoken in challenging China. As one of its closer neighbours, Australia took the lead in calling for an independent inquiry into China’s handling of the Covid-19 outbreak. This was a bold move as China has been Australia’s biggest export market for years. The reason Australia, uniquely among the developed industrial economies, had been able to boast of avoiding recession for three decades was primarily down to China’s relentless demand for Australian minerals, foodstuffs and other products. It tells us much about the fraught state of geopolitical tensions that an advanced country so economically dependent on China has been prepared to take a public stand challenging the CCP’s denials of wrongdoing.

Geopolitical fracturing

Today’s targeting of China as a threat to the world did not come out of the blue. By the end of 2017, the US had already declared China a ‘strategic competitor’. In June 2018, Australia banned the use of Huawei’s telecommunications equipment, and subsequently tightened controls on Chinese inwards investment, on grounds of national security. In March last year, the EU mimicked this approach, labelling China a ‘systemic rival’.

By last year, the US government had already gone well beyond talking about China in terms of the ongoing US-Chinese tariff and trade wars. For instance last October, before anyone had heard of Covid-19, US vice president Mike Pence castigated China’s behaviour as increasingly ‘aggressive and destabilising’. He said it had slashed ‘rights and liberties’ in Hong Kong, built a ‘surveillance state unlike anything the world has ever seen’, continued to ‘aid and abet the theft of our intellectual property’, and pursued military expansionism.

In fact, the ratcheting up of geopolitical pressure on China had been underway for some time before that. Almost a decade ago the Obama administration made the decisive shift in identifying China as a rising threat. In 2011, President Obama announced the ‘pivot to Asia’, marking the emergent political perspective that more assertive measures were needed to contain China. At the core of naming the East Asian region as the new focus for US trade and diplomacy was America’s evolving strategic relationship to China.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), eventually signed in early 2016, was presented as the key economic pillar of America’s Asian pivot. The TPP’s geopolitical role was hard to disguise as it sought to extend ties with all the major economies in the region, but with the notable exception of China. The hope was that this would reduce the signatories’ dependence on China, and bring them closer to the US. Alongside this economic initiative, the US strengthened military ties with Vietnam, Australia and the Philippines, and increased aid to Laos.

Contestation between the US and China simply took a blunter form when Trump entered the White House in 2016. Initially, he imposed tariff hikes against China in his declared mercantilist quest to protect US jobs, though this went alongside tariffs against Europe and other ‘friendly’ countries as well. However, the trade war with China soon escalated into an open technology war, with accusations of intellectual property theft and of threats to national security. The line between economic protectionism and geopolitical containment quickly became blurred, setting the scene for today’s offensive against China.

Solidarity with the Chinese people

The Chinese regime is a repressive autocracy with few qualms about using authoritarian means to protect itself. The world – not least the 1.4 billion Chinese people living in the mainland and in Hong Kong, as well as those under threat in neighbouring Taiwan – would be hugely better off with a democratic China instead. Thus actions taken by the inhabitants of Chinese territories to pursue freedom and democracy should be supported and celebrated by freedom lovers around the world.

The basic solidarity principle to follow is that to be genuine, freedoms have to be secured by ordinary people. History reveals that durable liberty and democratic politics are not things that can be brought about by government bodies, but only by the people themselves. Democracy is not defined by a set of imposed institutions but by a culture of association and collective action taken by the demos. This tenet is embodied in the right of people to national self-determination, to be able to decide their own political future.

Of course, Hong Kong people and democrats across China want outside support in their struggles for freedom – as do freedom-seekers in Syria or North Korea, or any other repressive regime. Under attack by their own governments, this is completely understandable. But the blunt historical record of intervention by external governments is that it makes things worse for the local people. Look no further than the seemingly endless war in Syria as outside forces try to out-manoeuvre each other as they attempt to advance their own interests. Yet it is the people of Syria who suffer most.

Western powers ‘exporting democracy’ to deserving locations has rarely gone well. Other recent interventions under the banners of human rights and spreading democracy have been a torrid experience for the common people at the receiving end, not least in Iraq, Libya and Afghanistan. The populace, who were suffering enough from local tyrants, has its ordeals intensified and prolonged by the destabilising interventions of stronger external powers, which use other people’s territories to pursue their own agendas. Just like with China-bashing today, those earlier campaigns were also motivated as being directed ‘only’ at the regimes, not at the people. That’s not how it has worked out for the Iraqi, Libyan and Afghan masses.

Given that today’s focus on China is the struggle for democratic freedoms in Hong Kong, it is useful to recall the actions there of a Britain that has now joined today’s anti-China crusade. The people of Hong Kong had just as few, if not fewer democratic rights during their 150 years of British colonial occupation than under the post-1997 ‘one country, two systems’ set-up within China. It was only as the clock ticked down to British withdrawal in 1997 that the last governor, Chris Patten, tried to rush through a quasi-democratic system in an attempt to aid local pro-Western politicians against Beijing loyalists.

Throughout British rule, Hong Kong governors, including Patten, had been appointed in London without any involvement of the ordinary people of Hong Kong. There was no such thing then, either, as ‘one person, one vote’. When last year Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, invoked emergency powers against pro-democracy protesters, it was telling that she used regulations Britain had introduced to its colony in 1922. The Emergency Regulations Ordinance was a response to strikes then at the city’s ports. In circumstances assessed as an emergency or a public danger, the ordinance allows the local supremo to make ‘any regulations whatsoever which he may consider desirable in the public interest’.

The British authorities had used these powers against anti-British protesters in 1967 to order the detention of a person for up to a year without giving any reasons. In response a year later, Henry Litton, then secretary of the Hong Kong Bar Association’s bar committee, wrote that ‘the powers which the Hong Kong government has at present over the liberty of the people of Hong Kong are as absolute as have ever been devised in the history of democratic government. The detention procedure is contrary to all ordinary standards of international behaviour as laid down by international courts and arbitration tribunals in decisions over many years.’

The substantive difference was that the territory’s unfree status then was enforced not by an autocracy but by a liberal democratic government. This reminds us that it would be naive to have illusions that Britain, the US, or any other Western liberal democratic state apparatus ever hands complete power to the demos in another country.

Five arguments against China-bashing

Here are five reasons that Western China-bashing is regressive, counterproductive and dangerous.

1) The most immediate act of solidarity we can provide to Chinese people fighting for freedom and democracy is to quash the West’s campaign of China-bashing. Western authorities meddling in China’s internal affairs – rhetorically and practically – make the prospects worse for democrats there, and around the world. The firm position is Western state non-intervention.

Governmental intrusion is an infringement on people’s capacity to determine their own lives. When outside governments seek to impose against China’s sovereignty, it is harder for the people of China to determine their own future. Better to only have to fight your own government to achieve freedom than have to take on external governments instead, or as well. As the British occupation of Hong Kong shows, Western governments cannot be trusted to be faithful friends of democratic progress.

More immediately, offensives from foreign governments give the Chinese government scope to play its own nationalistic cards and crack down harder on dissent at home, making struggle harder for local democrats. Western bombast alone, even before taking concrete steps to damage China or its leaders, provides the regime with ammunition to claim that China’s ‘era of humiliation’ at the hands of the West continues. This offers the regime more justification for taking extreme, sometimes brutal, measures at home and abroad.

Already in response to the Hong Kong street protests last year, the Beijing government and state-run media accused foreign forces of interfering with domestic affairs and supporting pro-democracy protesters. Last November China’s vice-foreign minister, Zheng Zeguang, told the US ambassador to China that passing the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act amounted to encouraging violence. Zheng demanded that the United States should ‘correct its errors and stop meddling in Hong Kong affairs and interfering in China’s internal matters’.

Again, it is worth standing back a moment to recall that this narrative of national humiliation that requires avenging began with Britain’s Opium Wars in the middle of the 19th century. It was Britain’s colonial occupation of the Chinese territory of Hong Kong from 1841 during the first Opium War that marked the start of what was originally called a ‘century of humiliation’. Recollect, too, that the proximate reason for those two wars pursued by Britain was to prevent pushback by the Chinese government against its own people being made addicted to the original opioid. This was a situation that the British government fought to retain in order to have a product from another of its colonial possessions to trade in exchange for desirable Chinese silks and porcelains.

Returning to the present, it is true that Beijing would probably continue to use the card of avenging national humiliation even without today’s actions and threats from Western governments. However, the present level of Western combativeness gives China’s leaders greater confidence and authority in pushing this line. In today’s fired-up circumstances, it is easier for Beijing’s leaders to denounce Hong Kong advocates of freedom as ‘pawns’ who have been hoodwinked by Western intruders.

What direct forms of solidarity from people outside China could help? Actions should aim at weakening CCP control. The democratic principle of self-determination implies a distinction between the economics of people’s lives and how these lives are conducted politically. Consistent with this approach, popular solidarity would be most effective in the political realm, impacting the potency of the CCP regime, rather than in the sphere of economics and normal business relations, which are mostly business-to-business, or business-to-people. Sometimes though, economics can encroach on politics, in which case we need to exercise specific judgment over what to say and how to act.

For instance, as a norm, national, or multinational, regulation or law should not restrict trade and capital flows into and out of China. However, if Western companies were found to be supplying the Beijing government with devices for repression, we should try to stop these supplies as they are aiding the suppression of Chinese people’s right to act.

A similar approach should be taken with regard to Chinese interventions abroad. Cross-border economic and business activities involving China, like China’s Belt and Road Initiative, should not be bound by third countries or international rules. Only the receiving countries should govern them. If any country’s authorities, including those of less developed economies, decide not to authorise Chinese inward investments or lending, or place conditions upon them, that is a matter between its people and their government. Again, other foreign authorities and international institutions should stay out of these bilateral matters.

However, if the Chinese government seeks to interfere in the domestic political lives of other countries, whether in sub-Saharan Africa or Latin America or Taiwan, then it is legitimate to denounce such interventions. These, though, are still not circumstances for other governments to intervene under any pretext. The same applies to the various territorial disputes over islands in the South China and the East China Seas. Unilateral actions of occupation by China should be deplored. But disputes are best resolved in negotiations between the respective Asian national states, without international or Western intrusion.

However, individuals or groups of people who want to take active sides in solidarity with the oppressed anywhere, including in China, should not be prevented or criminalised by their own governments for doing so. As positive examples, think of the International Brigades in 1930s Spain fighting Franco’s forces. Or, in recent times, of people from Western countries joining up to fight alongside Kurdish troops against Islamic fundamentalism. These are proud instances of democratic internationalism. They represent the direct opposite of national elites scapegoating other countries to serve their own particular ends.

Instead of going along with contemporary China-bashing we need to work out similar democratic, internationalist ways to act in solidarity with the Chinese people today. The guiding principle is that collective direct action by people to undermine the power of the CCP is going to be more helpful to democrats in China than intrusive actions taken by Western governments.

Instead of endorsing the governmental campaign of China-bashing, support for the Chinese people’s pursuit of popular freedom is also served by people in the West standing up for their own freedoms and democratic rights. Democracy and freedom is never secure and irreversible. People need to fight for them continually. For instance, the pandemic period revealed how quickly and easily freedoms could be curtailed, even in long-established Western democracies.

Standing up to fight for our own freedoms and liberties in our territories can inspire others towards the same ends in their countries. For example, the Brexit vote in 2016, motivated by a desire to return control of laws and regulations to locally accountable bodies, was an inspiration to critics of the undemocratic EU across the whole continent and beyond.

2) China-bashing diverts from addressing the real domestic sources of problems within the Western world – political, social and economic. It is always easy for elites to find a foreign country or a foreign force of some type to blame for their troubles, not least because these problems often have foreign implications. Today, China serves as the primary foreign scapegoat, with Chinese economic strength identified as the cause of Western economic weakness.

This is worse than an intellectual distraction: it means giving up on acting in the one place where people can make a difference – within their own national borders. This is where people have the scope to make use of the democratic political channels that have evolved within nation states. Our most effective feasible field of action is at home.

People can be rightly appalled at the cruel and unjust behaviours of foreign governments, but they have immeasurably more capacity and agency to act to change their own circumstances. A demos that comes up with problem-solving programmes can change things, whether through elections, or by campaigning, or by more radical forms of civic insurrection.

Yet when elites successfully pursue a foreign blame game, they can undermine domestic criticism and evade political contestation at home. For instance, the trigger for China-blaming has been many governments’ shambolic handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. In an attempt to shirk responsibility for extra deaths, economic turmoil and general disarray, governments have been quick to jump on the anti-Chinese bandwagon.

Other unwelcome domestic political developments get blamed on external forces, especially misinformation from foreign sources. We heard this refrain often as an explanation for the Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s presidential election win. It allowed disappointed elites to downplay the homegrown factors, not to mention their own roles, in driving these popular results. It is highly possible that we will see an increasing focus on Chinese cyber-warfare, as well as information warfare, to explain the difficulties of Western political elites. Already there are claims of online attacks targeting the US presidential campaign emanating from within China by groups with links to the Chinese government.

Economic malaise in particular gets blamed on outsiders. For instance, the weakening of domestic industrial capacity, conventionally called ‘deindustrialisation’, has the corollary of more industry leadership abroad. However, the latter is more a consequence than a contributor to productive decay within one’s own boundaries. The use of these deflecting antics also means that the prime internal sources of economic problems continue and fester.

The causes of joblessness and inadequate wages are often attached to trade or ‘globalisation’, or blamed on the unfair practices of foreign governments. In the 1980s and 1990s, US politicians blamed Japan for America’s deindustrialisation. That phase dissipated when Japan entered its own protracted depression from the early 1990s.

Instead, over the succeeding decades the spotlight turned on to the next rising power. Thus Steve Bannon can assert that today’s huge economic and financial crisis, precipitated by the pandemic, ‘could have been avoided if the CCParty had a modicum of decency and a modicum of respect for their own people, for the Chinese people’. Less jaundiced commentators recognise that today’s economic crisis is a continuation of the over-indebted stagnation trends underway well before Covid-19 came on the scene.

The failures in the US, Britain and most other advanced industrial countries to create sufficient new businesses and sectors that can generate good jobs for the jobless are domestically rooted. They are not due to Japan, China or any other faster-growing country. Instead they are the consequence of systemic structural economic problems that national governments have failed to address. In fact, these governments’ conservative status quo-orientated policies have reinforced the home-produced barriers impeding economic development and decent growth. Blaming China avoids having to account for these governments’ own failings and responsibilities.

We are being encouraged to view China as the great evil causing our economic, social and political disarray, diverting us from the only terrain where we can act with considered effect to address these problems – that is, in our respective national territories. Unless we reject the blame being heaped on China – or any other foreign source – we become complicit in the elites’ evasion of responsibility.

3) Continuing the economic theme, not only does China-bashing dodge the domestic foundation of economic decay, it can also compound economic weakness by rolling back the economic gains of internationalisation. World society – east and west, north and south – has benefited from the economic advantages of specialisation and economies of scale within an international division of labour.

This progress has been uneven and irregular, and not all countries have prospered to the same extent. Nevertheless, it would be regressive for governments of the advanced industrial countries to try to ‘decouple’ China from their economies, and to seek directly or indirectly to limit China’s domestic and international economic development. Yet such economic and technological warfare is well advanced. We have already noted restrictions on business relations with Chinese companies operating internationally. Existing national bans on links with Huawei could spread to other Chinese overseas suppliers in areas such as funding, financing, high-speed train infrastructure building, nuclear energy technology, and much more.

Aiming to fetter China’s rise would, firstly, have adverse economic effects for the people of China. Despite being a one-party autocracy, few critics dispute that China’s take-off since the late 1970s has taken about 800million people out of poverty, and raised living standards substantially across its entire population. Depending on their effectiveness, Western attempts to isolate China economically would slow the momentum of its further expansion, and could even reverse some of the past gains in living standards for its inhabitants.

Closing off trade, investment and business relationships would also impair the economic health of the very Western countries imposing the restrictions, boycotts and sanctions. With their own economies grinding ever slower at home, even the most productive of Western businesses have come to rely on China and the rest of the East Asian region for supplies, markets and locations for production.

Without the surplus gained from international activities centred on China’s economic flourishing, Western firms would have one of their most important coping mechanisms diminished if not decimated. In the absence of other measures taken by these businesses, their productivity rates will fall, their employees in their home countries will suffer, and their customers will likely face higher prices and therefore lower living standards.

The potential cost goes way beyond a delay in rolling out 5G networks if Huawei technology is excluded. It is about breaking links with an economy that has been directly and indirectly supporting Western prosperity. China has not only been supplying cheaper products for Western consumers and lending enormous sums to Western governments — it has also been spurring innovation. Whether China is a world technology leader in particular areas, or still a challenger, there is little doubt its presence has already driven progress in many sectors: not only telecommunications equipment, but also solar power, battery technologies for electric cars, and drone technologies. In contrast, putting up barriers to Chinese economic and business linkages in an attempt to decouple from it will reinforce the existing protectionist trends that are already hindering economic renewal and damaging Western economic prospects.

The indirect effects for prosperity and livelihoods in the rest of the world are harder to nail down, but they could also be substantial. A world economy from which China is excluded would be an economic move backwards, impacting on billions of people. China has been the most important single contributor to global growth for many years. This has helped to raise economic activity around the world, not only within the advanced industrial countries but also within the less developed ones. With developing countries already hit hard by the impact of pandemic lockdowns, an enforced isolation of China by Western powers could impair its uplifting effect on poorer economies.

Chinese foreign direct investment and lending into many less developed countries in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and South America has helped these countries raise employment, productivity levels and generate higher living standards. All this economic progress would be set back by today’s China-baiting drive to disrupt its international economic relationships.

4) China-bashing is also potentially divisive within the West at the expense of people of Chinese heritage who live in, study in or visit it. Targeting the Beijing leadership as a danger to Western interests gives sanction to a less specific sentiment directed against Chinese people in general. This would be detrimental to the huge Chinese diaspora and to Chinese students and tourists, and it could spread to other East Asians of a similar appearance, including Japanese and Koreans.

Even though many of the Chinese living outside China do so because of their opposition to the regime at home, that wouldn’t protect them from prejudice, abuse and attacks. The vilification of ‘China’ from within the political elites authorises a generic prejudice against Chinese people.

In the early weeks of the Chinese-originated virus hitting Europe there were reports of hostility to some Chinese people, including residents of Chinese origin, in Italy, France, Canada and Britain. Although hostile incidents seemed to have been limited, and were probably talked up by some Western identity activists, this is not grounds for complacency. Fiercer official China-bashing that appeals to earlier notions of a ‘yellow peril’ could have unpleasant and potentially violent consequences for Chinese-looking people in the Western countries.

5) China-bashing is dangerous for global peace. A huge mismatch already exists between economic and political power in the world. The centre of global wealth creation has shifted decisively from west to east, specifically from the US to China. However, the distribution of political power still reflects the very different economic world institutionalised after 1945. This incongruity has already generated great tensions between the declining and the expanding nations and regions. Resolving this dissonance amicably is the biggest geopolitical challenge facing the world’s leading nations.

This potential for discord is not going to evaporate with the passing of time. In fact, the consequences of the pandemic look like exacerbating the disparity. China, and East Asia more widely, are so far being less impacted economically than the mature Western industrial countries. As a result, the east-west economic divergence is likely to amplify.

Meanwhile, the West’s collective resistance to China assuming a larger political role in the world, commensurate with its economic resources, has already fuelled the reaction of a forceful ‘China first’ approach. Following this path, China’s pandemic antics and its aggressive ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy have raised the stakes further.

More assertive Chinese foreign policy is actually not new. In recent years, President Xi Jinping has on several occasions advocated ‘a fighting spirit’ to his foreign policy officials to encourage a more militant style. This intensifies international friction. For instance, there has already been a backlash against some of China’s statements during the pandemic war, even among some erstwhile friends of China. This spiralling slanging match is making it less likely that Beijing’s leaders will revert to their previous gradualist approach to extending their global influence.

For instance, in response to the Australian government challenging China’s handling of Covid-19, Chinese-controlled media compared Australia to ‘chewing gum stuck to the sole of China’s shoe’, warning ominously that ‘sometimes you have to find a stone to rub it off’. The Beijing government followed up with punitive tariffs on Australian barley, banned certain beef imports, and warned of consumer boycotts of Australian wine.

Reciprocal threats can easily move beyond wars of words and tariff squabbles. The co-existence of China-bashing with a more combative style of Chinese domestic and foreign policy creates a vicious cycle of heightening tensions. Even if all major governments – east and west – seek to avoid military conflict, a momentum of escalating confrontations can soon take a militarised form.

This danger of open conflict is aggravated by problems at home for all the main players. The Beijing regime may appear solid and secure, but that’s the same for all autocratic governments until they fall. While the lack of democratic mechanisms is explicitly built into Chinese governance, this has one drawback for the CCP politburo: they have less of a handle on where they stand in the eyes and minds of the Chinese populace. The famed ‘obedience’ of Chinese people may be a delusion. Uncertainty about the CCP’s real grip on society stirs its misgivings. This can compound the risk of it overreacting.

At the same time, the failings and insecurities of Western governments, both globalist and non-globalist, inflates the potential for accidental confrontations. Western elites that lack assured values, clear direction and courage are prone to taking arbitrary and shortsighted actions that could escalate out of control.

These actual or perceived weaknesses of the respective regimes, though of a different character, are conditions that can spark greater recklessness abroad. Western governmental China-bashing is a symptom and intensifier of this incendiary mix. Their aggression, rhetorically and practically, is likely to be answered by firmer Chinese actions. Even if initiated as ‘defensive’ measures, these can soon morph into offensive behaviours – and will certainly be perceived as such.

In this way, louder Western predictions about China becoming more aggressive abroad become self-fulfilling. Subsequent anticipation of having to deal with a militarised crisis leads to preparing for one. And preparing for one brings it closer to reality. This is where the China-bashing campaign could culminate.

Phil Mullan’s new book, Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents, will be published by Emerald Publishing later this year.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.