Scotland had a lockdown culture long before Covid

New Labour’s ‘politics of behaviour’ was enthusiastically adopted by the Scottish government.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Whatever the truth of the threat we face from coronavirus, it is always worth bearing in mind that the way science is understood and used is often determined by the prevailing political and cultural norms. For example, one of the key political trends of the past two decades has been the rise and rise of what is called the ‘politics of behaviour’.

The politics of behaviour is a New Labour invention. It has been adopted by all the political parties but is most wholeheartedly embraced by self-proclaimed ‘progressives’. Developed as a form of micro-politics that obsesses about little things, it is also a form of politics that has infected the regional assemblies most of all. If you want to know what will be banned next, it is always advisable to check out what’s going on in the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament. This helps to explain why up here in Scotland, the baby steps we are taking out of the lockdown are even more babyish than in England.

One could argue that Scotland has had a ‘lockdown’ culture for some time. When it comes to locking or clamping down on what we can say and do, Scotland leads the way. Whether it is criminalising words, trying to stop people from smoking or drinking, or attempting to make us eat ‘correctly’, the Scottish government has been at the forefront of attempts to limit the freedom of the public and to ensure that we all ‘behave responsibly’.

Take the recently proposed hate-crime bill – a bill that goes much further than England’s counterpart in attempting to criminalise words. Indeed, if passed in its current form, it could lead to preachers being arrested in churches for reading ‘incorrect’ sections from the Bible. Scotland was also first to criminalise even the lightest smack. It also notoriously attempted to give every child in the country a Named Person – essentially a state guardian, to oversee their every need – until the Supreme Court ruled this to be illegal.

With such an attachment to the politics of behaviour, it is no surprise to find that the Scottish government is dragging its feet on easing the lockdown. Underpinning this form of politics is a patronising distrust of the public and a tendency to want to over-regulate what we do in our daily lives.

The term ‘politics of behaviour’ was first used by Labour MP Frank Field who argued in 2003 that we had moved from a ‘politics of class to a politics of behaviour’. His prime concern was with antisocial behaviour, but his idea was quickly taken up by Tony Blair and other New Labour politicians like Tessa Jowell who, a year later, described the politics of behaviour as ‘one of the most fascinating challenges facing the government’.

Whether it is called the politics of behaviour or ‘positive welfare’, or indeed ‘nudge policies’, the general idea of this approach is that government should get involved to ensure that we adopt what they call ‘positive lifestyles’. The politics of behaviour was a framework through which New Labour attempted to change the nature of the state and to transform the relationship between the state and the public.

The target of the Blair governments was our individual private habits and ways of behaving, our parenting strategies, our diet and forms of exercise, our alcohol consumption, our gambling habits and even our sex lives. This was a different type of politics, engaged far less by big ideas and plans for society than by an obsession with personal behaviour, with the minutiae of everyday life.

Looking at the question philosophically, the great American thinker Christopher Lasch described the difference between acting and behaving in the following way:

‘Whereas every action is unique and idiosyncratic, behaviour falls into patterns that repeat themselves in a predictable fashion. Action, whether it is reckless and impulsive or deliberate and discriminating, is the product of judgement, choice, and free will, whereas behaviour is automatic and reflexive.’

Lasch’s distinction is between the freedom and thought associated with the idea of acting, compared to the mindless, unthinking nature of people who simply ‘behave’. Action is aware of itself, he notes, whereas behaviour is merely habitual and unconscious. Tony Blair and his ilk were far more interested in developing a politics that engaged with us as children who could be trained to behave rather than as free adults who could think for ourselves.

Discussing the same issue of action versus behaviour, the political philosopher Hannah Arendt identified the important creative and dynamic nature of acting, something she described as having the capacity to ‘initiate’, to change and to transform. Those who behave, she noted, would never use their initiative but always stick to the beaten track.

At the level of politics, then, attempting to engage with the way we behave rather than the way we act reflects a type of governing that engages us at our most passive. In this scenario, we are not to be thought of nor engaged with as thinking people who can make our own choices. Indeed, for the politician or expert who wants us to behave in a certain way, ‘acting’ becomes a problem because it is based upon our free will.

What behaviour managers rely on is unthinking compliance and mindless conformism. Political citizens who think for themselves become a barrier to expert-led politics and policies. And so part of the process of the politics of behaviour is to infantilise the public by engaging with us as patients or clients, as immature adults who cannot be trusted with decisions about how to live.

One of the offshoots of the politics of behaviour, over the past two decades has been the emergence and proliferation of what is called ‘awareness raising’. But don’t be confused by this term. Awareness raising has little to do with raising our level of knowledge or understanding. If it did, we wouldn’t need to be given the same messages, repeatedly, to be made ‘aware’, time after time after time. Awareness raising has not developed to enhance our knowledge, or to help us to think and to act; it is more akin to a form of Pavlovian conditioning, a mechanism for training us about how to feel and how to behave.

The emergence of the politics of behaviour, nudge policies, awareness raising and so on represents a change in the way that a key section of the modern elite engages with the public. It helps, in part, to explain the relentless way in which the ‘Stay Home’ message has been used and abused over the past two months. It also helps to explain why Scotland is clinging on to this mantra while England tries to move on.

At a time when the spirit, the will and the initiative of the Scottish people are needed like never before, it is time to demand that the government stops telling us how to behave and allows us to start acting.

Stuart Waiton is a sociology and criminology lecturer at Abertay University in Dundee.

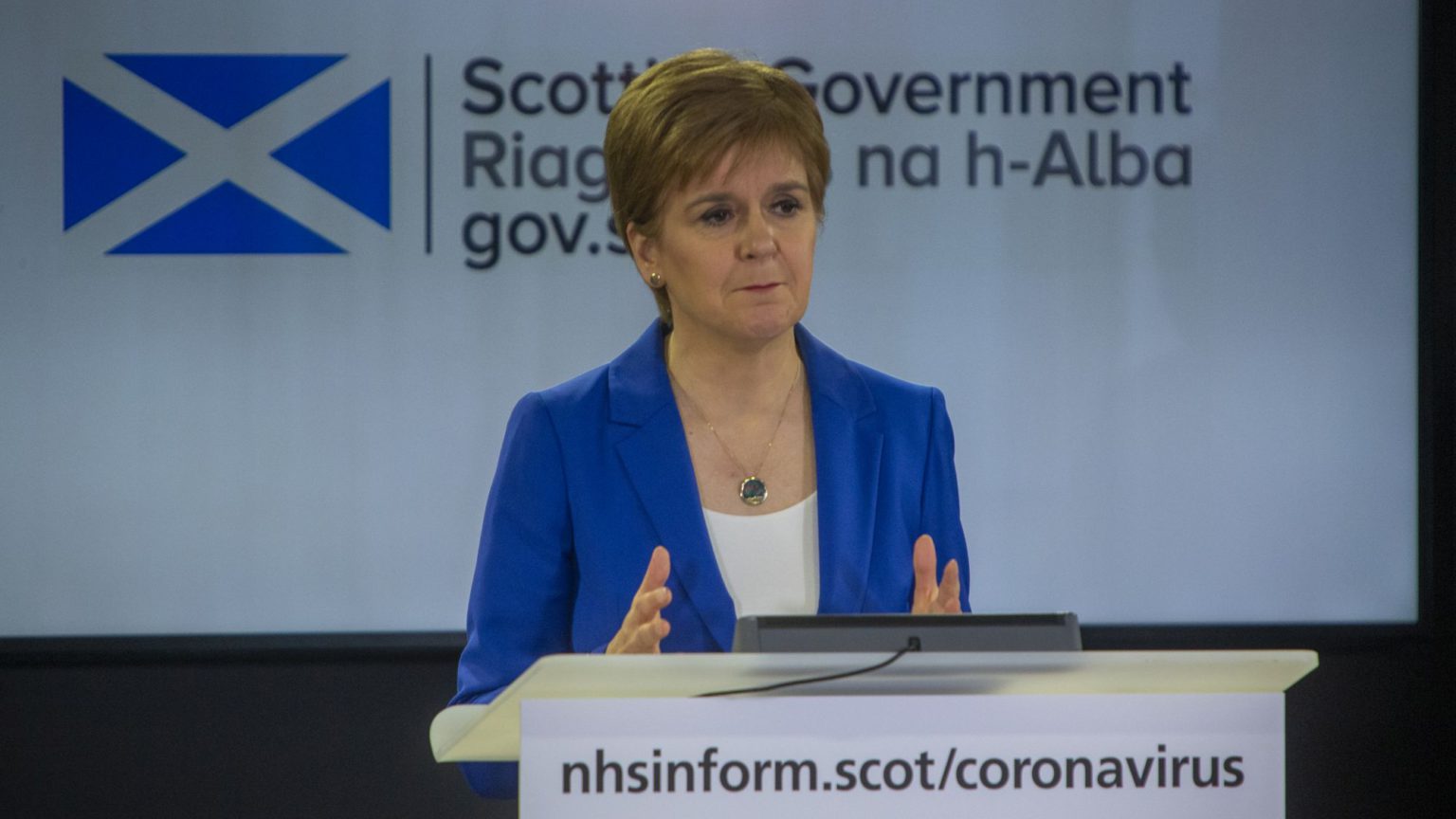

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.