A short step from contact-tracing to mass surveillance

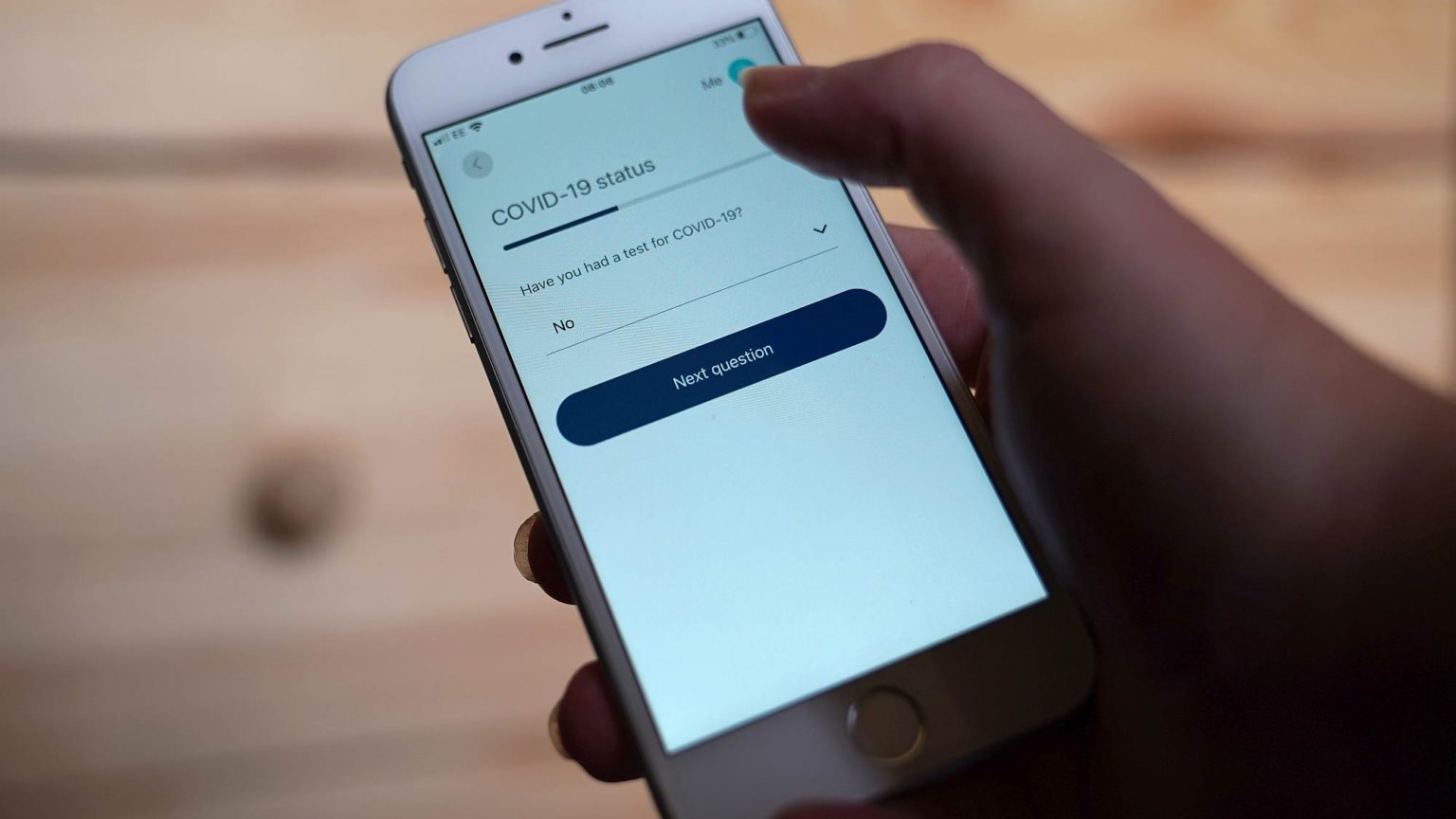

The NHS's promised contact-tracing app could easily pose a threat to our freedoms.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Whenever the dust settles on the corona era, and historians look back at what made it significant, there will be plenty to chew over. They will discuss the scientific models, government policies, the individual heroes, the economic fallout and the shift in the relationship between China and the West.

But, however seismic these phenomena are, historians have written about these types of things before. They have explored the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the Spanish Flu, the Cold War and the ‘Blitz spirit’.

What is potentially novel and unique about the happenings of the corona era is that Western states began to relate to their citizens through an app. This represents a social and administrative revolution between people and their governors, fuelled by the ostensibly admirable motivation to save lives and protect public health.

Yet where that revolution could lead can be glimpsed in China’s social-credit system, which ranks citizens according to such behavioural criteria as their trustworthiness.

That is because, used to their potential, apps can reveal almost every significant aspect of the lives of the people connected to them, from browsing history to romantic conversations and stress levels. State access to such personal data has the potential to benefit public health, which is why NHSX has developed its first ‘contact tracing’ app.

Appearing before the Joint Committee on Human Rights, Matthew Gould, the head of NHSX, was at pains to point out how limited the data collected will be, and that the app would only pass on information that is voluntarily given. The version of the app being trialled on the Isle of Wight, requires your postcode area and information about your symptoms and it generates a unique identifier number. This data is then used to alert your phone contacts to prevent the spread of a virus.

The current model sounds benign enough, and comparisons with China could seem alarmist. Still, it would only take one or two more data fields to enable the government to begin to identify individuals, given that some postcode areas contain fewer than 10,000 households. When asked about the possibility of the app requiring more data in the future, Gould could only offer assurances that when they do, such requests will be ‘voluntary’ and in ‘plain English’.

But just how voluntary is voluntary? There will inevitably be social pressure on individuals to download and use the app. Furthermore, many public-health regimes incentivise or penalise citizens for not ‘voluntarily’ participating. Israel, for instance, places citizens lower on waiting lists if they do not voluntarily donate their organs. It is not difficult to imagine how a voluntary system could become mandatory in practice if not in law, especially if it were to evolve into an immunity passport enabling essential work and travel.

Questions have been raised about where data is to be stored and who gets to see it. When quizzed about the latter, Gould could only say that there was ‘no definitive list’ regarding which government agencies would have access. Controversially, the UK is planning to operate a centralised data system rather than the de-centralised type most other countries are using. NHSX admits that centralised models are less data-secure, less private, and leave the app unable to inter-operate with those in other countries.

And here we get to the heart of the issue. De-centralised models are sufficient to enable contact tracing. The only reason Gould could give to justify a centralised model is the power such data gives to government agencies. However, such potential can only be realised if more information is required of users in the future. Thus, the government has intentionally chosen a model incentivised towards continually asking for increasing amounts of private information.

If the NHSX app is not to evolve into something like a Chinese-style social-credit score or health passport, bespoke legislation and regulation will be required to set hard boundaries. Legislation requires a formal assessment of how proportionate government use of personal information will be, balanced against the legitimate aims of the project. The proportionality bar is likely to be high, given that personal information is afforded special protection under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Such rights assessments cannot be properly conducted by the Information Commissioner, the only body with sanctioning power currently overseeing the project.

Worryingly, UK health secretary Matt Hancock denies the need for new safeguards or scrutiny around a project that has the potential radically and permanently to transform the way citizens relate to their governments. This ought to concern everyone who cares for the future of our freedoms in the corona era.

Ryan Christopher leads the work of ADF International in the UK.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.