Long-read

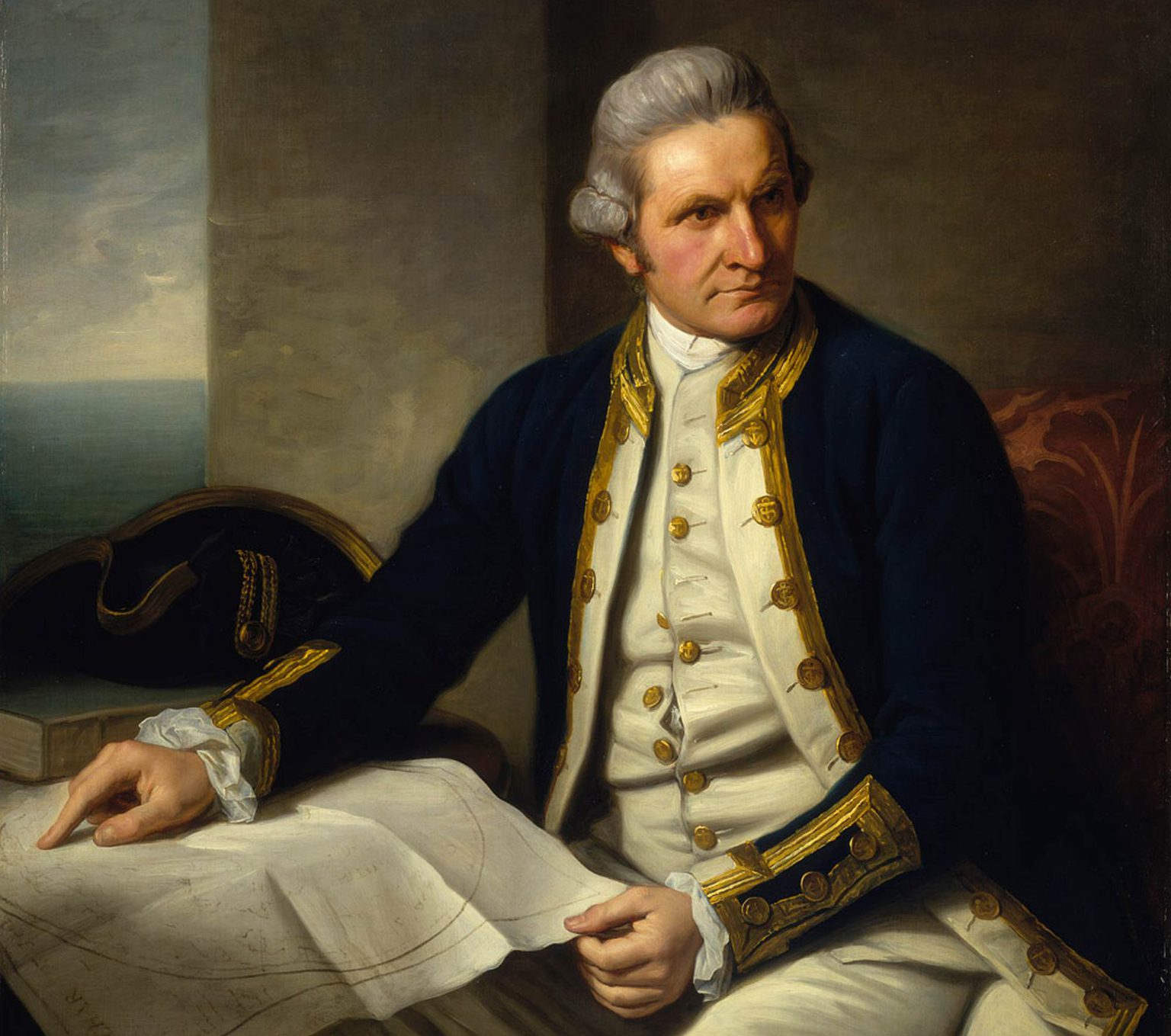

Captain Cook and the heroism of the Enlightenment

250 years on, the Endeavour’s voyage to Australia remains an inspiring testament to the human spirit.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The three voyages of James Cook, between 1768 and 1780, substantially increased humanity’s knowledge of the globe.

Prior to his odysseys, the Earth was divided into two separated hemispheres: the northern, which was largely but not entirely charted; and the southern, which was largely uncharted, and yet to be fully discovered by the more technologically developed world north of the equator. Cook’s voyages, his achievements in seamanship, in navigation and cartography, his relentless will to explore both hemispheres, opened the way for contact between different regions and different peoples of the world, which had hitherto been impossible.

Cook’s achievements ought to speak for themselves. He mapped more of the globe and sailed further south than anyone before him. When other mariners perished in the abyss of oceans, Cook could pinpoint his location to within a mile. He even pioneered a cure for scurvy that saved countless lives and increased the longevity of voyages.

He was also one of the very few men from the lower classes to rise to senior rank in the Royal Navy. Men followed Cook to the ends of the Earth and beyond, and his attitude to the indigenous peoples he encountered was enlightened and compassionate.

This month marks the 250th anniversary of Cook charting the east coast of Australia, then referred to as Terra Australis Incognita – the unknown land of the south. He accomplished it during the three-year voyage of the Endeavour, the first of his three great voyages that marked him out as the mariner of the Enlightenment, if not all time.

Cook was born in 1728 in north Yorkshire, the son of a farm labourer. His father’s employer paid for Cook to undergo five years of schooling until, at the age of 16, he was sent to Staithes to work in a grocer’s shop where he slept each night under the counter. Eighteen months later he moved to Whitby to be apprenticed into the merchant navy, working on coal ships between the Tyne and London. At the end of his apprenticeship he worked on trading ships in the Baltic, progressing through the ranks. Then, at 23, he enlisted in the Royal Navy at the very bottom of the hierarchy.

He was relatively old for such a move, but was soon promoted. During the Seven Years War, he served in North America, mapping the entrance to the Saint Lawrence river as well as the coast of Newfoundland. The latter expedition resulted in a map so accurate it was still in use in the 20th century. The key to his accuracy was the astronomical observations he conducted to calculate longitude. This enabled him to use precise triangulation to establish land outlines. Cook’s cartography brought him to the attention of the Royal Society and the Admiralty, who jointly arranged the voyage of the Endeavour. It was to be an expedition of scientific discovery, departing England in August 1768.

The initial purpose of the expedition was to observe and record the transit of Venus across the Sun – to help determine the distance of the Earth from the Sun. This would be done at the Pacific island of Tahiti. Cook was 39 and promoted to lieutenant in order that he could command the ship. Endeavour was a bark, which is a sailing ship with three or more masts. It had been built for moving coal, and it was a type of vessel Cook knew extremely well.

There were 94 on board, including a scientific team led by Joseph Banks, an independently wealthy naturalist who had been through Eton, Harrow and Oxford. Banks was an aristocrat, and brought with him the eccentricities of his class as well as some of his own. Alongside him were the naturalist Daniel Solander, the astronomer Charles Green, the artists Sydney Parkinson and Andrew Buchan. Banks also brought along two negro servants – Thomas Richmond and George Dillon – which was apparently the fashionable thing to do among his class at the time. The scientific team collected and recorded samples throughout the journey at sea and on land.

At Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago at the southernmost tip of South America, Banks’ servants died of exposure in a snow storm. As the ship rounded Cape Horn, Banks shot an albatross. He intended initially to treat it as a scientific specimen, but then decided he would eat the animal in a stew, recording the recipe in his journal.

In sailing mythology, the albatross embodied the souls of dead sailors. It was a creature to be revered, not stewed and eaten. Given Endeavour was about to sail west into the uncharted Pacific, from where other vessels had failed to re-emerge, mutiny was a possibility for Cook even without Banks’ blasphemy. It would be three months before they would see land again. Some must have wondered if they ever would, and one of Cook’s crew threw himself overboard.

But Cook could lead. He used the lash on sailors more than Captain Bligh, who famously provoked a mutiny on the HMS Bounty in 1789. But somehow sailors trusted Cook. He once wrote: ‘The man who wants to lead the orchestra must turn his back on the crowd.’ Leadership was about doing what was necessary, not what was popular.

For example, Cook knew that, when no fresh fruit was available, it was going to be difficult to ward off scurvy. The answer lay in ensuring his crew ate the less palatable pickled cabbage. Cook didn’t understand how it worked, but he knew that it did and ordered his crew to eat it; when some didn’t, he gave them a dozen lashes. Later he resorted to the reverse psychology of only serving sauerkraut at the captain’s table – and one way or another not a single member of his crew died of scurvy. This was unheard of on such a voyage.

Having rounded Cape Horn at the end of January 1769, the Endeavour reached Tahiti on 13 April. The island had been chosen because a British expedition led by Samuel Wallis had landed there the previous year. Several of Cook’s crew had sailed with Wallis and good relations were more easily established with leading Tahitians, including Tuteha, the chief of the area around the landing site. Cook was well aware that the people of the Pacific Islands were vulnerable to exploitation, and he set out very specific rules that his crew should abide by. It began: ‘To endeavour by every fair means to cultivate a friendship with the Natives and to treat them with all imaginable humanity.’

Cook was the mariner of the Enlightenment, if not all time

Permission was given for the visitors to build a fort, which became a trading post. During the stay, the British became acquainted with Tupaia, a Tahitian priest and navigator. Tupaia joined the Endeavour, sailing on to New Zealand and Australia. Cook and his astronomer observed the transit of Venus on 3 June 1769. He then opened a second packet of sealed orders from the Admiralty. These instructed him to search for new lands, in particular the great southern continent which would, ‘redound greatly to the Honour of this Nation as a Maritime Power, as well as to the Dignity of the Crown of Great Britain, and may tend greatly to the advancement of the Trade and Navigation thereof’.

When land was found his orders were to ‘observe the Nature of the Soil, and the Products thereof; the Beasts and Fowls that inhabit or frequent it, the fishes that are to be found’.

The artist Alexander Buchan died of epilepsy in Tahiti, but Banks and Solander continued to collect and collate samples at a relentless rate for Sydney Parkinson’s quick hand. During the entire voyage, Parkinson made nearly a thousand artworks – of plants and animals, and of lands and their peoples – working in difficult circumstances. At one point his cabin was plagued by flies that fed on his paints. Banks subsequently had 738 copper plates engraved with Parkinson’s work so his drawings and water colours could be published, but never completed the project. It wasn’t until 1988 that the great Florilegium was published. In all Banks and Solander collected nearly 30,000 dried specimens, increasing the known flora of the world by a quarter. Parkinson was to die from dysentery later on in the voyage at Java. And Banks’ own journal of the Endeavour voyage was not published until 1962.

Cook was the second known European to land on New Zealand. His circumnavigation of both islands disproved the theory in Europe that it was part of the great southern landmass, as the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman had surmised a century before. Endeavour then made its way north east until, on 19 April 1770, Lieutenant Zachery Hicks called land from a masthead. They were looking at a coastline that no European had ever seen before, and it wasn’t where Tasman recorded Van Diemen’s Land (known today as Tasmania) as being. As if to welcome them to Australis Incognita, the wind raised three water spouts, snaking up from the sea. Two died away quickly but the third hung in the air for some time, with Banks describing it in his journal thus:

‘It was a column which appeared to be about the thickness of a mast or a midling (sic) tree, and reachd down from a smoak colurd cloud about two thirds of the way to the surface of the sea…When it was at its greatest distance from the water the pipe itself was perfectly transparent and much resembled a tube of glass.’

Cook named the headland Point Hicks and continued heading north. They landed on 29 April, with Cook asking 18-year-old Isaac Smith, cousin to his wife Elizabeth, to be the first ashore. Banks and Solander wasted no time spreading out a sail on the beach and covering it with 200 quires of drying paper for botanical specimens. Endeavour stayed in the harbour for a week, and Cook named it Botany Bay on his departure.

His journals of the voyage were published on his return and established him as a world figure among the scientific community. He was, like the First Fleet that came to Australia after him, stunned by the vividness and abundance of bird life.

‘Two sorts of beautiful perroquets’, he told Parkinson, ‘a very uncommon hawk, pied back and white… The iris or its every broad, of a rich scarlet colour inclining to orange, the beak was black, the cera dirty grey yellow, the feet were of a gold or deep buff colour like the king’s yellow.’

There were varying degrees of contact with Aboriginal people as Endeavour progressed up the coast. As Cook himself writes:

‘From what I have said of the Natives of New Holland they may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb’d by the Inequality of the Condition.’

On 11 June Endeavour ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef. The coral tore its timbers and it began to sink. There were life boats enough for fewer than half of crew members, and the three pumps could barely keep pace with the incoming water. Crew member Jonathan Monkhouse told Cook about a method that was used on a leaking ship he was once aboard in the Atlantic. It was called ‘fothering’, and involved knitting fistfuls of wool and oakum to a sail, tying ropes to each corner, and smearing animal dung over it, before then wrapping it under the ship. The pressure of water would then push the bolstered sail into the hole. In Endeavour’s case it worked, and her crew were saved. The Endeavour limped to shore for repairs.

She finally returned to England in July 1771, and Cook became a sailor of international repute. During the American War of Independence Benjamin Franklin ordered his navy not to interfere with Cook’s missions, for ‘he was a common friend to mankind’.

Cook’s achievements have lived on in the public memory for over two centuries. There are statues of him in Melbourne and Sydney. In 1934 the cottage where he was born was purchased and taken to Melbourne to be rebuilt brick by brick. The final space shuttle was called Endeavour, and Gene Rodenberry’s Star Trek surely alludes to Cook, in the shape of James T Kirk and his spaceship, the Enterprise, with its ‘five-year mission to seek out new life forms…to boldly go where no man has been before’.

Yet today things are different. On Australia Day in 2018, paint was thrown on Cook’s statue, and he stands charged with colonialism, and facilitating the dispossession of Aboriginal people. This year a planned circumnavigation of Australia in a replica of Endeavour was criticised by many as insensitive.

James Cook and his achievements have fallen foul of the inane culture wars, and he finds himself out of favour, traduced. It would not be done to be seen in Sydney’s best cafés reading a biography of the man. At a time when we find ourselves threatened by forces we do not fully comprehend, Cook and his crew can serve as an inspiration, a reminder of the resilience, of the insatiable curiosity of humanity. He embodies a spirit – beyond talk of colonialism and national pride – an indefatigable spirit of mankind that is fearless and optimistic, a belief that we can find answers and prevail.

Michael Crowley is a dramatist, and the author of The Stony Ground: The Remembered Life of Convict James Ruse and First Fleet.

Pictures by: Getty Images

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.