Fully Automated Vulgar Marxism

Aaron Bastani's much-hyped manifesto woefully misunderstands Marx, capitalism and class struggle.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

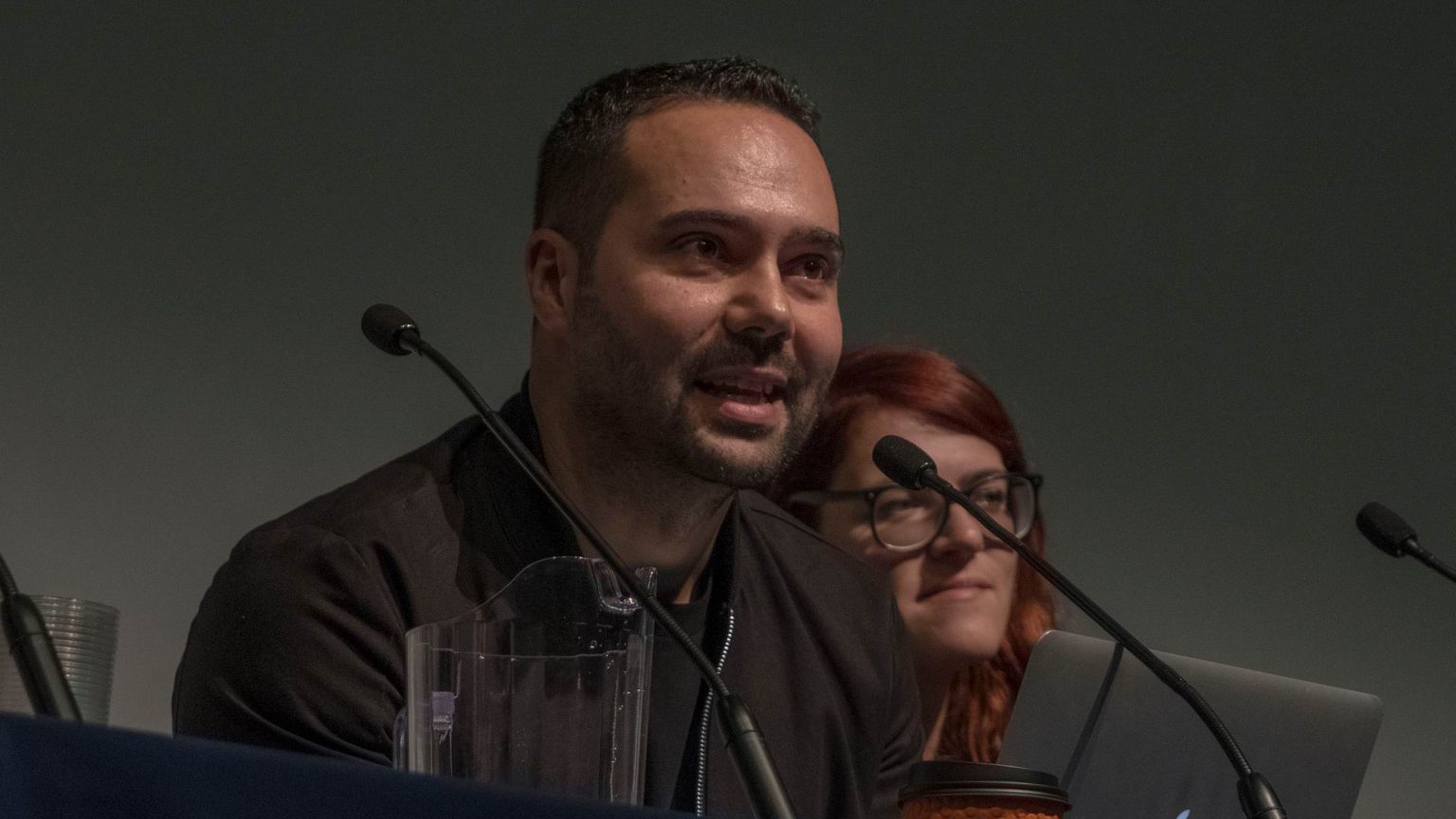

Corbynism, the ideology that had sustained the Labour Party since 2015, suffered a crushing defeat in last month’s General Election. But while Corbyn himself may be about to retire to the backbenches, his far younger outriders are likely to be around for a while yet. Chief among them is Aaron Bastani, the co-founder of the London-based alternative-media outlet Novara Media. His book, Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto (FALC), therefore provides a valuable window into some of the ideas that informed the broader Corbyn movement.

The immediate impression one is left with after reading FALC is that it appears to have had two authors. One is a techno-optimist; the other is autocratic, with firm views both about which technologies should be developed and which should be avoided – and also, more tellingly, about how people should live under them. Parts of the book anticipate a brave and exciting new world enabled by technological developments, while other parts are imbued with today’s illiberal and constraining zeitgeist. One author emphasises that the future is not determined, but can be shaped by politics, while the other sees capitalism as following a predetermined process of collapsing under its own contradictions. One pays homage to the ideas of the Enlightenment. The other’s prescriptions negate the Enlightenment ideals of liberty and risk-taking.

Parts of FALC exude excitement about the potential of renewable technologies, especially solar power. In support, Bastani references the pro-decarbonisation International Energy Agency. Elsewhere, though, Bastani rejects nuclear power and calls for state bans on shale-gas fracking. Yet no mention is made of the fact that the same International Energy Agency’s sustainable-development scenario endorses both nuclear and shale gas. It seems that FALC adopts a partial and predisposed approach to expert advice.

Again, one author sees technological progress as setting us all free, while the other recommends limiting our freedom. The potential of an epoch of luxury for all is an uplifting sentiment. Yet Bastani’s alter ego then smuggles in all-too-conventional ideas about restricting what we consume. FALC paints its readers a world of milk and honey, but it then regresses into one where considerations of animal welfare, environmental depletion and climate change dictate that we should only drink synthetic milk and eat artificial honey. This is presented as ‘freedom of choice’: we can all have the freedom to choose to consume milk, but only as long as it is produced by cellular technology machines, rather than by cows, goats, sheep or any other living thing. In reality, this denies genuine choice.

FALC’s dualism shows that taking a stand against fashionable techno-pessimism does not necessarily equate with politically progressive ideas. In this, it mirrors the way many Silicon Valley enthusiasts of new technologies have made their peace with the anti-democratic features of our era. Think of the Tesla, Space X and Hyperloop pioneer Elon Musk, who is rather disparaging about the general public: ‘[P]ublic transport is painful. It sucks. Why do you want to get on something with a lot of other people… there’s like a bunch of random strangers, one of whom might be a serial killer.’

Bastani and his Novara Media outfit are, of course, best known for the backing they gave to Corbyn and Labour. Labour gets just a single mention in its pages, but this manifesto does call to mind another one: Labour’s ill-fated 2019 General Election manifesto. That said, FALC does make the pre-election pledges of Corbyn and John McDonnell appear rather modest by comparison.

While Labour’s manifesto famously promised free broadband for all by 2030, Bastani goes much further and proposes five ‘universal basic services’ be made available to everyone for free: not just health, education and internet access, but also housing and transport. And there is even less pretence at ‘fully costing’ them than in Labour’s own manifesto. It remains an open question as to how Bastani and his colleagues ultimately assess Labour’s electoral collapse, but so far there has been a reluctance to interpret it as a rejection of their political approach.

The enormous praise offered to Bastani’s book by many on the old left tells us more about the desperate state of left-wing politics than it does about Bastani’s thesis. ‘Must-read’, ‘incredibly ambitious’, ‘absolutely critical’, ‘fascinating’, ‘genius’, are just some of the quotes on the dust jacket from the likes of Paul Mason, Grace Blakely and Owen Jones. But despite its provocative title, there is hardly anything original in FALC. And what is unconventional has little to do with classical notions of communism. It seems that in today’s turgid times, an optimistic eulogy to our technological potential is enough to qualify as pioneering.

Old-hat ideas

Bastani’s analysis of contemporary technological trends is not novel, even if his 20-page obsession with mining asteroids is a little unusual. Much of his description of a post-industrial, knowledge-based economy has been around since the 1970s (see Daniel Bell’s influential 1974 work The Coming of Post-Industrial Society). Bastani’s central theme of a ‘Third Disruption’ – following the first disruption of the Neolithic agricultural revolution, and the second disruption of the Industrial Revolution – directly recalls Heidi and Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave.

Published almost 40 years ago, The Third Wave was the second in the Tofflers’ futurist trilogy, between Future Shock in 1970 and Powershift in 1990 – two other texts that also contained many of the themes featured in Bastani’s manifesto. Since then, there have been decades of endless discussion of the supposedly transformative character of the ‘information age’. Bastani is excited in writing about all this now, but it is not breaking new ground.

Nor is Bastani’s belief in the coming end of capitalism original. For well over a hundred years Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalism’s dynamics has been vulgarised into a crude determinism by one left-wing grouping after another. Marx’s understanding has been distorted to express these groups’ craving for an imminent collapse of capitalism. The genuine difficulty of winning mass political support for the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist system has always attracted leftists to the hope of an inevitable breakdown of capitalism.

Yet the notion of a ‘coming collapse’ was alien to Marx’s entire method of thinking. He illustrated this in Capital, Volume III, where he spent more pages explaining how capitalism survived by compensating for its fall in the rate of profit than he did in demonstrating the tendency for the rate of profit to fall. For Marx, the capitalist crisis did not indicate that capitalism would eventually give way. Rather, the resolution of each crisis would always be a matter of political contestation.

Bastani’s specific contribution to this tradition of left-wing ‘breakdown’ thinking is to fuse technological determinism with the old idea of a ‘crisis of overproduction’. ‘Capitalism, at least as we know it, is about to end’, he writes. He suggests that the consequences of technological advances are the ‘exponential’ reduction in costs, and the prices of things, ever closer to zero.

This applies not just to information goods, but also to other commodities, including minerals and energy, and, also, to labour. In parallel, continued technological development brings about an excess of production leading to a condition Bastani calls ‘extreme supply’. This supposedly cripples capitalism’s market mechanism, and becomes an existential threat to capitalism. He claims capital just cannot accept ‘abundance’, but instead is forced to create ‘artificial scarcities’.

This is a one-sided and misleading view of how capitalism operates. It is even contradicted by historical appearances, as for most of the 19th and 20th centuries capitalism has been reducing prices and increasing supply. Over the years, most goods and services have cheapened. Compare the cost today with that in the past of phone calls and other communications services, or of clothing, air travel, electronic goods, never mind computing power. The prices of all these have fallen dramatically over the decades.

So how does FALC substantiate the claim that these ever-present features of capitalism will bring about its dissolution now? Why do almost 200 years of technological change only now precipitate the end of the market economy? Bastani’s core assertion is that technology-driven ‘extreme supply’ causes the profit motive to fail: its ‘internal logic starts to break down’. However, there is little in the way of explanation of this supposedly terminal condition.

In fact, historically, capitalism has always expanded alongside abundance. The capitalist tendency has been to produce more volume, reducing the value of each unit, with businesses adapting to these changing circumstances. Bastani fails to account for how the market system has adjusted, generally successfully, to a whole range of ‘extreme’ supplies and falling prices. Indeed, what is striking over the past couple of decades has not been the accelerating pace of falling prices, but the opposite: the flatlining of the productive investment and productivity growth that is required to reduce prices and boost supply continually. That contemporary shift towards stagnation would have been a more fruitful area for Bastani to explore to uncover capitalism’s limitations.

Instead, consistent with Bastani’s support for today’s empty socialist parties, his technologically driven ‘extreme supply’ idea evokes an old notion associated with early social-democratic thinking: capitalism’s supposed crisis of ‘overproduction’. This debased Marx’s exposition of the tendential overaccumulation of capital into one of its appearances: an overproduction of commodities. A supply of too many goods and services relative to the demand for them was believed by many leftists to result in ruinous, crisis-precipitating gluts.

This ignores how the semi-spontaneous character of the market mechanism means that a mismatch of the over-supply of commodities has always accompanied capitalist production. Such a perennial feature cannot explain the intermittent recurrences of economic crisis in the 20th century. Nevertheless, many socialist theoreticians stuck to their obsession with the overproduction of things. Bastani’s pronouncements about ‘extreme supply’ echo this approach. His version no better justifies the common yearning for an approaching demise of capitalism.

The end of work?

Bastani does sometimes sense that this faith in the progress of technology bringing about the end of capitalism is sidestepping something important. This is the matter of agency that used to figure rather prominently within the communist tradition. Which social force can act to lead society towards communism?

Here, Bastani proclaims the need to build a workers’ organisation to achieve his vision of luxury communism. Fair enough, though his suggestion for a ‘workers’ party against work’ (my emphasis) does draw out his peculiar view of communism as a world without work. This again is not a new opinion. It follows the thinking of the French New Left writer André Gorz, who in 1980 declared that due to automation, ‘the abolition of work is a process already underway’. The suggestion is that robots will eventually do everything now done by people, and none of us will have any work to do.

For Bastani, conventional anxieties about automation creating a jobless society morph into a ‘post-work’ nirvana of all play and leisure. Paralleling his wish for capitalism to disappear of its own accord because of modern technologies, he anticipates the arrival of a post-work world determined by the same forces. As a result, technological development can eliminate the necessity for political action – both to take society beyond capitalism, and also to abolish labour exploitation. Technological determinism substitutes for social struggle. Having brought up the vital matter of agency, Bastani allows it quickly to recede again.

The idea of communism as the end of work is where Bastani most distorts the writings of Marx. Bastani reads him as saying that under communism work is akin to play. It is well known that Marx identified the working class as the only social force that had the power and interest to overthrow capitalist social relations. Bastani, though, interprets Marx’s elevation of the working class as being ‘key to a future society… only because its revolution was uniquely able to eliminate work and thereby end all class distinctions’. Marx argued no such thing.

For Marx, communism would be a classless society, not a workless one. In the Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875), he explained that with the much greater development of the productive forces than was possible under capitalism, a communist society could ‘inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.’ This is a stirring ambition. It is also the opposite of a belief in the death of productive work.

Earlier, in a response to criticisms that he had not ‘proved’ the concept of value in the first volume of Capital, Marx famously wrote to Ludwig Kugelmann, a social-democratic confidant in Hanover, that:

‘Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish. Every child knows, too, that the masses of products corresponding to the different needs require different and quantitatively determined masses of the total labour of society. That this necessity of the distribution of social labour in definite proportions cannot possibly be done away with by a particular form of social production but can only change the mode of its appearance, is self-evident. No natural laws can be done away with. What can change in historically different circumstances is only the form in which these laws assert themselves [my emphasis].’

Here, Marx was illustrating his historically and socially specific method. While the social form that work takes changes in different production modes – slave-based production, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and communism – in all types of society people have to work. Without work any society would soon perish. But what ‘every child knows’ seems not to be known by Bastani.

Marx’s vision of a communist society was not one without work, but one where no particular type of work is forced upon people. As he, with Friedrich Engels, wrote in The German Ideology (1845-6), under capitalism a man is:

‘[A] hunter, a fisherman, a shepherd, or a critical critic and must remain so if he does not wish to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity, but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic’

However, when we reach Bastani’s luxury communism, it seems people will no longer need to work at all – as hunters, fishermen, shepherds or critics, or as anything else. Instead, these activities (or at least the ones that continue after we all become vegetarians – no hunting, fishing or shepherding required) will be done by unsupervised, self-determining robots.

Real freedom

In contrast, Marx saw the enduring attraction of communism as the possibility of real freedom, which included labour being ‘not only a means of life but life’s prime want’. Yes, developing the material conditions sufficiently could create luxuries for everyone and less time in work, but the deeper gain for humanity was about extending freedom, choice and control. People would for the first time enjoy a genuine flexibility of work (very distinct from today’s rendering of work ‘flexibility’ as meaning flexi-hours, occasional working-from-home and having your work phone on 24/7). It would also bring a meaningful choice over what people did. For Marx, the ‘springs of co-operative wealth’ would flow more abundantly, enabling the ‘all-around development of the individual’.

Bastani has displaced a communism where we come together to create a better world for everyone with one of endless leisure. Permanent leisure can sound appealing, but this would soon wear off. As many retired people today find, even for those lucky enough to have a good income, full-time leisure can soon become a tedious and sterile existence. Humanity surrenders something essential to it when it is deprived of creative purpose.

Bastani’s insensitivity to the possibilities of the full development of the individual under communism is consistent with his top-down view of how we should live now in preparing for it. Marx’s vision of ‘losing our chains’ is shelved in favour of a manifesto where ‘enlightened’ folk like himself can decide what chains are good for us in our daily lives – what we should consume and not consume; how we should travel and not travel; how we should power our societies and how we should not.

It is a shame that Bastani’s fascination with technology has diverted him from the urgency of promoting, more strongly than his techno-optimism, the non-material values of autonomy and liberty. Perhaps it is the glare of limitless solar power and other technological possibilities that blinds him to seeing that it is only the pursuit and attainment of these freedoms that make communism a worthy goal.

Phil Mullan’s latest book, Creative Destruction: How to Start an Economic Renaissance, is published by Policy Press.

Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto, by Aaron Bastani, is published by Verso Books. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Wikimedia Commons, published under a creative commons license.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.