The key to contentment? Embrace strife and woe

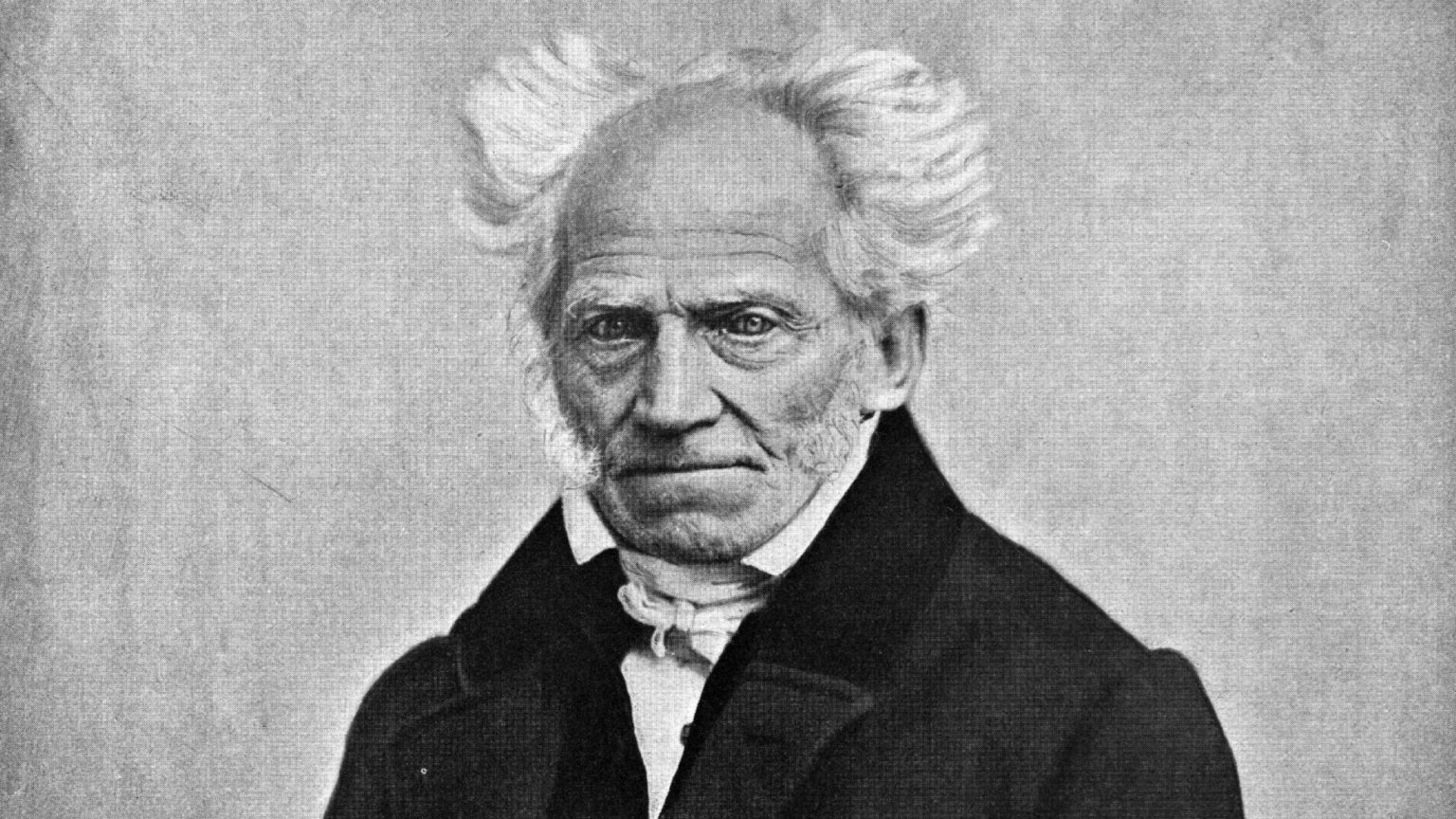

Today’s overly emotional young people should read some Schopenhauer.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Children today are suffering from ’emotional obesity’ because they are encouraged to talk about their feelings too much, according to a behaviour expert.

In her new book, Sweet Distress, the teacher and therapist Gillian Bridge says that allowing children to wallow in their emotions is akin to giving them sugary treats: it makes them feel better in the short term, but it’s bad for long-term mental health. She argues that instead of teaching pupils introspection, they should be given a sense of being part of history, to be taken outside of themselves.

This is not merely a matter for teachers, she says. It is part of a wider problem, concerning the way society deals with feelings. ‘What we’re doing a lot of the time – getting people to focus on their emotional wellbeing – is making things worse, not better’, she told The Times recently. ‘It’s taking people who are vulnerable to begin with and asking them to focus inwards. This focus on “I, myself and me” is the problem.’

Introspection can indeed be a pointless and perilous pursuit. It can lead to worry or finding faults with oneself – faults that can never truly be repaired. If it really worked, the self-help industry would no longer exist, having solved the eternal problem of mankind’s unhappiness and woe.

Contrary to a myth that has been with us since the 18th century, and propagated by the wilder elements among the Enlightenment movement, by political utopians, the advertising industry, psychotherapists and the pharmaceutical industry, mankind, and men, can never attain a utopia or utopian state of mind.

If you believe happiness to be the norm, or live in expectation of its arrival, you are, paradoxically, only going to end up more unhappy. This is what the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer believed.

Widely caricatured as the philosopher of misery, Schopenhauer wasn’t trying to make us feel depressed by his ostensibly gloomy writings; rather, he was trying to liberate us from false expectations. As he wrote in his most influential work, the two-volume The World as Will and Representation (1819, 1844): ‘There is only one inborn error, and that is the notion that we exist in order to be happy… So long as we persist in this inborn error… the world seems to us full of contradictions.’

He would have wise counsel for today’s youth, who have been taught to focus on their feelings. He wrote in his final work, Parerga and Paralipomena (1851): ‘What disturbs and renders unhappy… the age of youth… is the hunt for happiness on the firm assumption that it must be met with in life. From this arises the constantly deluded hope and so also dissatisfaction. Deceptive images of a vague happiness of our dreams hover before us in capriciously selected shapes and we search in vain for their original.’

The ultimate lesson to be drawn from Schopenhauer is that the key to happiness is not to seek it. As one of his disciples, a certain Friedrich Nietzsche, put it: ‘The right way of life does not want happiness, turns away from happiness.’ Nietzsche concluded that life was primarily about struggle. To embrace strife and woe: this is the emancipatory war that lets us finally become content and complete.

Defining sexist language

There is currently a petition calling upon Oxford University Press to change the ‘sexist’ definitions of the word ‘woman’ in some of its dictionaries. It has been signed by 30,000 people.

It was launched by the PR consultant Maria Beatrice Giovanardi, who found that some OUP dictionaries contain such synonyms to this word as bitch, piece, bit, mare, wench, bird, bint, biddy and filly. Sentences to show use of the word include ‘Ms September will embody the professional, intelligent yet sexy career woman’ and ‘I told you to be home when I get home, little woman’.

The petition says that the sentences depict ‘women as sex objects, subordinate, and/or an irritation to men’ and calls on OUP to ‘eliminate all phrases and definitions that discriminate against and patronise women and/or connote men’s ownership of women’.

The petition misses the point on two counts. First, it is the duty of a dictionary to describe what a word means and how it is used, not as you or the editors wish it to be. Most dictionaries have sexist words in them for the same reason they have racist and rude words in them: because people use them that way.

Secondly, if there is sexism in the world, isn’t it better that a dictionary, in alluding to reality, draw attention to that fact by explaining how it is expressed in language? Or do we pretend it doesn’t exist, and erase expressions of sexism from the lexicon?

Shakespeare in German

It was recently revealed that the late Michael Redgrave, one of the great Shakespearean actors of the 20th century, preferred reading the works of the Bard in German translation. Vanessa Redgrave told a Financial Times event last month that her father, who had studied at Heidelberg University, ‘knew German very, very well’, and he ‘claimed King Lear in German was better than Shakespeare’s English’.

This makes sense. Not only were the Germans, particularly Goethe, responsible for launching the cult of Shakespeare in the 18th century, but Germans have persistently claimed that he sounds better in their language.

There is a good linguistic reason for this. The English used by Shakespeare is closer to German than today’s English is. Most famously, Shakespeare used the now archaic second-person familiar singular version of you, ‘thou’, which still today has its equivalent in ‘du’. The two are even conjugated similarly in both languages. ‘Du kannst’ is German for ‘thou canst’, as in ‘I do protest I never injured thee, But love thee better than thou canst devise.’ (Romeo and Juliet, Act 3, Scene 1)

Shakespeare also rarely uses the verb ‘to do’ in an auxiliary manner. Instead of ‘did you see him today?’, the Bard reverses the subject and verb to make a question, as in German: ‘Where is Romeo? Saw you him today?’ Nor does Shakespeare use the progressive construction (‘I am going; look how I’m going’), a construction that doesn’t exist in German. He employs only the Germanic plain present tense: ‘I go; look how I go.’ Negation in Elizabethan English also follows a German pattern. Rather than ‘I don’t know him’, it is ‘I know him not.’

The idea that Shakespeare’s work sounds better in German is not outlandish, because it kind of is in German already.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, is published by Societas.

Picture by: Getty.

Rod Liddle and Brendan O'Neill

– live in London

Podcast Live, Friends House, London, NW1 2BJ – 5 October 2019, 2.30pm-3.30pm

To get tickets, click the button below, then scroll down to The Brendan O'Neill Show logo on the Podcast Live page.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.