‘If the state had treated people equally, none of this would have happened’

Eamon Melaugh on the Battle of the Bogside and the birth of the Troubles.

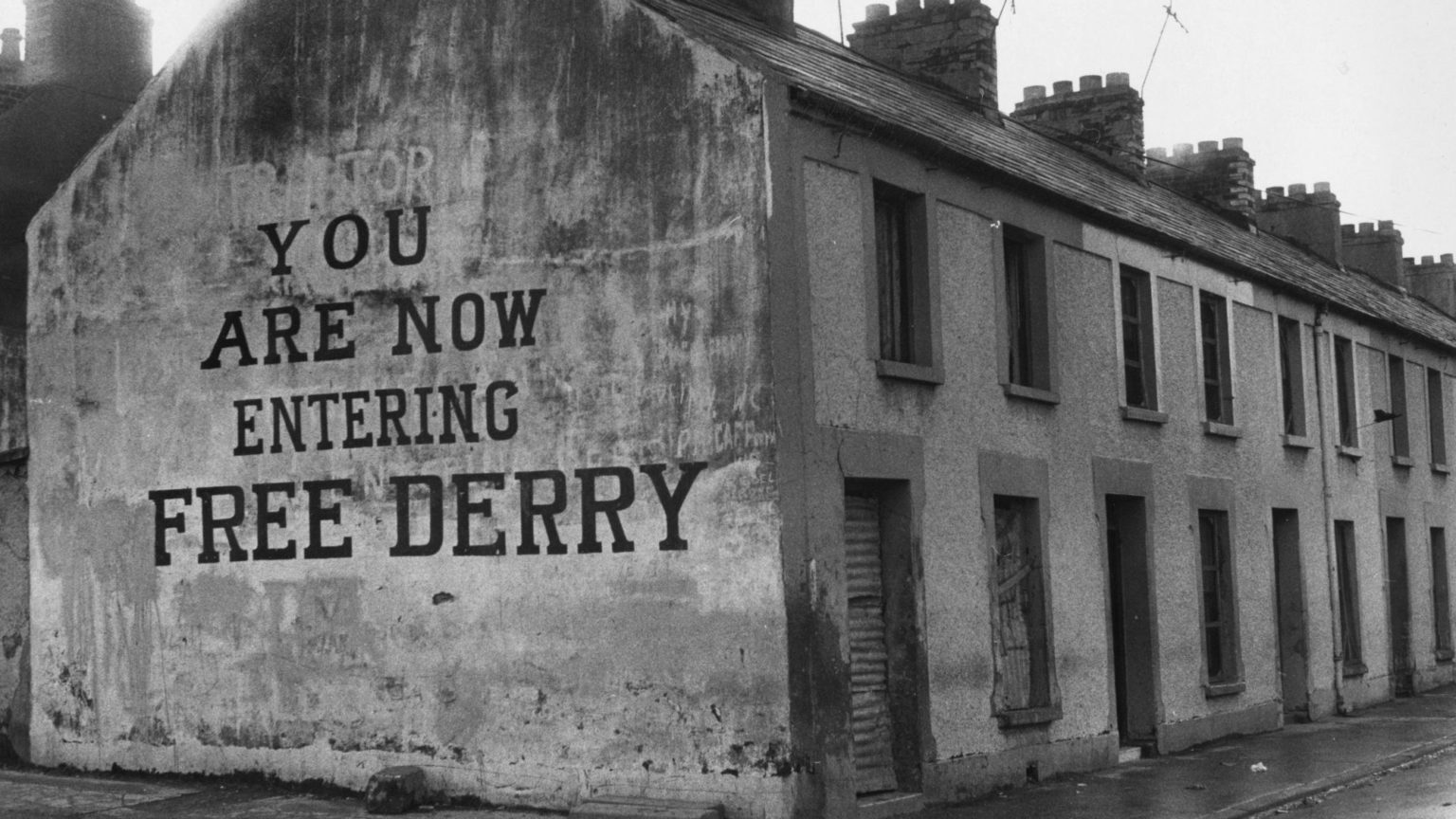

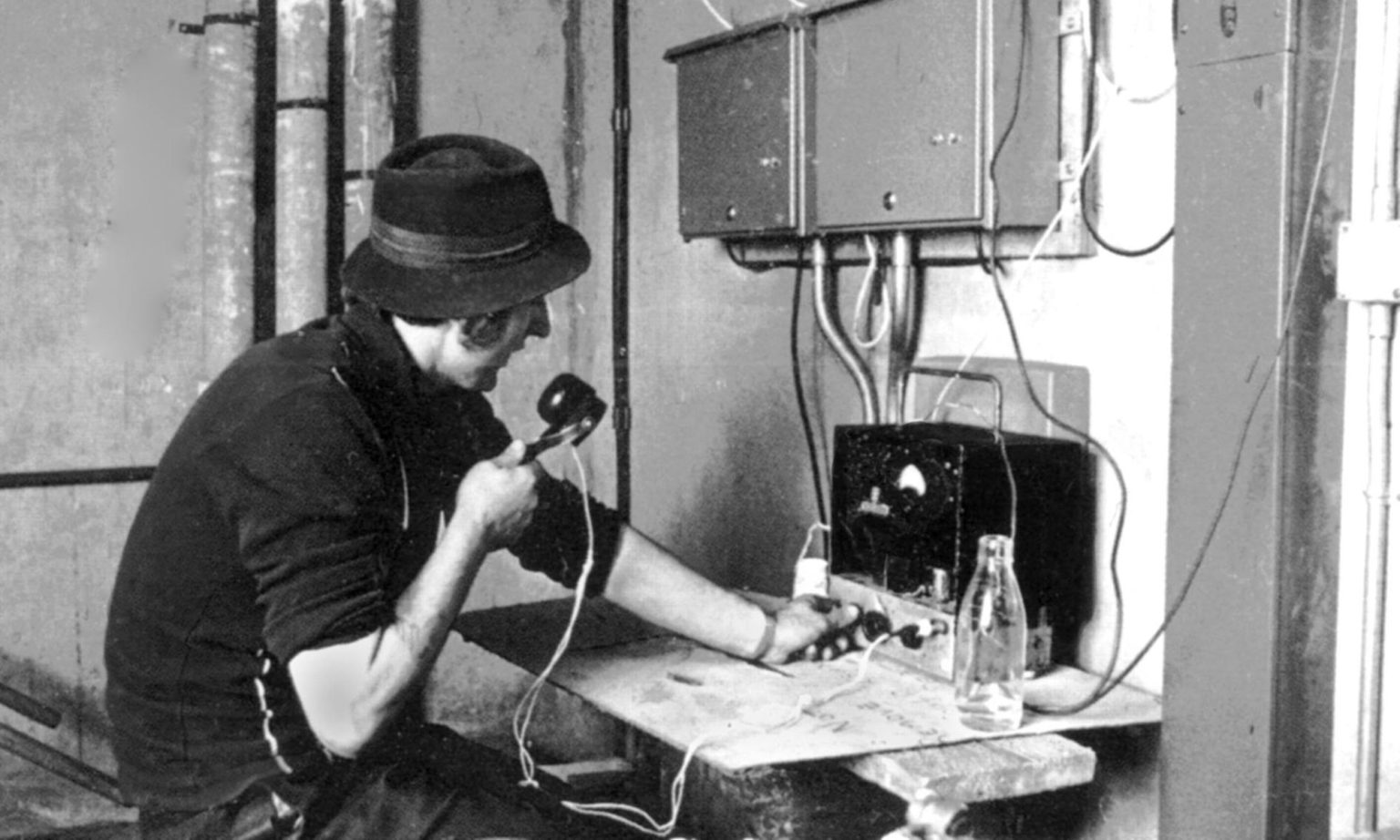

Fifty years ago to the day, Eamon Melaugh was in a small annex at the top of the Rossville Flats in the Bogside, a deprived Catholic area in the Northern Irish city of Derry (or Londonderry, as it is known to many Protestants), broadcasting on a pirate radio station as a battle raged beneath. The Catholic residents were defending their territory from the police by throwing stones and petrol bombs from behind makeshift barricades. ‘It was utter chaos’, Eamon tells me. ‘There was nothing planned. There was nothing provided for. People were rioting day and night.’

I’ve spoken to Eamon on many occasions about his key role as a civil-rights activist in the early days of the Troubles. (He’s my uncle.) He has been a lifelong socialist and an advocate of non-violent direct action, and has been present for most of the major events in Derry’s recent history. His impromptu radio broadcasts took place during the three days of riots which became known as the ‘Battle of the Bogside’, culminating in the first deployment of British troops in Northern Ireland. Fifty years on from this momentous act of resistance against state oppression, I meet with Eamon, now 86, at his home in Derry to hear his account of how these events came to pass.

‘I grew up amid bigotry and hatred’, he says. ‘I was born in Bridge Street, just outside the Derry walls. But in 1948 we moved to the prefabs in the Brandywell area. And there was hatred on both sides, I have to tell you. It was sort of justified on the Catholic side, if it can ever be justified, because they were the innocent victims of a ruthless oligarchy of Unionist politicians.’ Eamon, who is of Catholic background, wanted to help break this stronghold. ‘Quite frankly, I was determined that I was going to get the system by the scruff of the neck and give it a good shaking. I was not going to hand on to my children the legacy that my parents had handed on to me.’

‘When the state was formed in 1921’, he explains, ‘James Craig [Northern Ireland’s first prime minister] declared it “a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people”. We didn’t have normal politics then. We’ve never had normal politics in the north. The political system was controlled by the landed gentry. Catholics were systematically discriminated against in all aspects of life. They were trying to starve the Catholics on to the immigrant boat for England.’

Derry was the most egregious example of gerrymandering in the province. Electoral wards had been drawn in such a way as to ensure Protestant dominance. ‘We had a Unionist controlled Corporation’, says Eamon. ‘One third of the population were Unionists, but they could elect 12 councillors. The Catholics who had a two-thirds majority could only elect eight.’ The situation was made worse due to the lack of universal suffrage; only ratepayers were entitled to vote, meaning that those who were not tenants or did not own property were excluded. It was in the interests of those in power, therefore, to ensure that housing for Catholics was limited. Many were left living in squalid conditions in the Bogside, the Brandywell and the Creggan estate.

‘The Bogside was the most densely populated area of its size in the whole of Europe’, Eamon tells me. ‘Most of the houses would have had dual occupation. Some of them had triple occupation.’ Eamon joined Sinn Fein in the early Sixties, but soon grew frustrated with its lack of interest in these kinds of social issues. ‘I wanted to talk about housing and unemployment, but I was told quite ferociously that we were here to achieve a United Ireland. I was told that the politicians could deal with the social problems.’

But this was clearly not the case. Eamon organised regular protests at the council meetings at Derry’s Guildhall. ‘I would start speaking and the Unionists would walk out’, Eamon recalls. ‘On one occasion I got out of the public gallery, walked the length of the hall, got up into the mayor’s chair and banged down the gavel. I called for an emergency people’s resolution to build 2,000 new houses. And the nationalists didn’t say a word.’ With such a corrupt political system, it was always going to be up to local radicals like Eamon to effect any kind of change.

The lack of resolve from republicans led Eamon to co-found the Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC) with Bridget Bond and Matt O’Leary in February 1968. ‘We were fighting against Neanderthal politicians’, says Eamon. ‘I used to watch them going into the cathedral every Sunday, with their prayer books under their arms, praying to God on a Sunday but preying on the Catholics in the town.’ The DHAC was to become instrumental in the civil-rights march in Derry on 5 October 1968, the event that Eamon co-organised which most historians cite as the beginning of the Troubles.

Eamon had invited the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) to Derry at the end of August, but he understood that the march could never go ahead were it not for its support. ‘I’d promised the NICRA there would be thousands on the march, but I knew there wouldn’t be’, he admits. In his book, War and an Irish Town, Eamonn McCann (co-organiser of the march) recalls the moment a delegation from the NICRA executive visited Derry to discuss Eamon’s plan: ‘We met in a room above the Grandstand Bar in William Street. Melaugh, as the man who had thought of the idea, delivered a pep-talk before we went in to meet the delegation: “Remember, our main purpose here is to keep our grubby proletarian grip on this jamboree.” It was good advice. It was immediately clear that the NICRA knew nothing of Derry.’

According to McCann, this was the reason the NICRA accepted Eamon’s proposed route into the Diamond (the square within the city walls) without question. ‘This was holy sanctified Unionist territory’, Eamon tells me, ‘and there was no way the police were going to allow it to be desecrated. So I knew full well that the march would be banned.’ A few days before the event, Eamon met with a prominent journalist who told him there was ‘bad news’: William Craig, the minister for home affairs, had indeed banned the march and instructed the police to ‘wipe the Derry streets clear of demonstrators’. ‘That’s not bad news’, Eamon replied.

I ask Eamon whether he was worried about the violence that might ensue. ‘When I went out on the Saturday to march, I knew what was coming. I had six white hankies in my pockets to act as bandages, and that’s exactly what they were used for. The police were all waiting for us with drawn batons. I selected that route to provoke them into violence. And I told the marchers: when our blood flows, Stormont goes.’

For this strategy to work, the DHAC had to make sure that there was wide coverage of the event in the media. Eamon had already contacted the Irish television channel Telefís Éireann, and had met with a reporter for the Observer, Mary Holland, in the City Hotel in Derry a week before the march. ‘I said, “Look, Mary, we’re going to get savagely beaten. There’s going to be blood on the ground. You should be there.” And she came on the march with us.’

As anticipated, the protesters were attacked as they attempted to march into Unionist territory, and the sheer brutality of the televised images caused international outrage. Eamon was arrested the next morning and put on trial for organising the banned parade along with Eamonn McCann and Finbar O’Doherty. But by that point, as he puts it, ‘the genie was out of the bottle’. He recalls being bundled into a police car and witnessing scenes of ‘ransacking’ in the town. ‘After that we had riots on the streets almost on a daily basis. All hell had broken loose. But my argument was always to organise ourselves into a peaceful political working-class group which would bring down the Unionist government. But nobody was listening. There was a lot of anger. And, quite frankly, some of the young boys were enjoying the violence. They had a ball.’

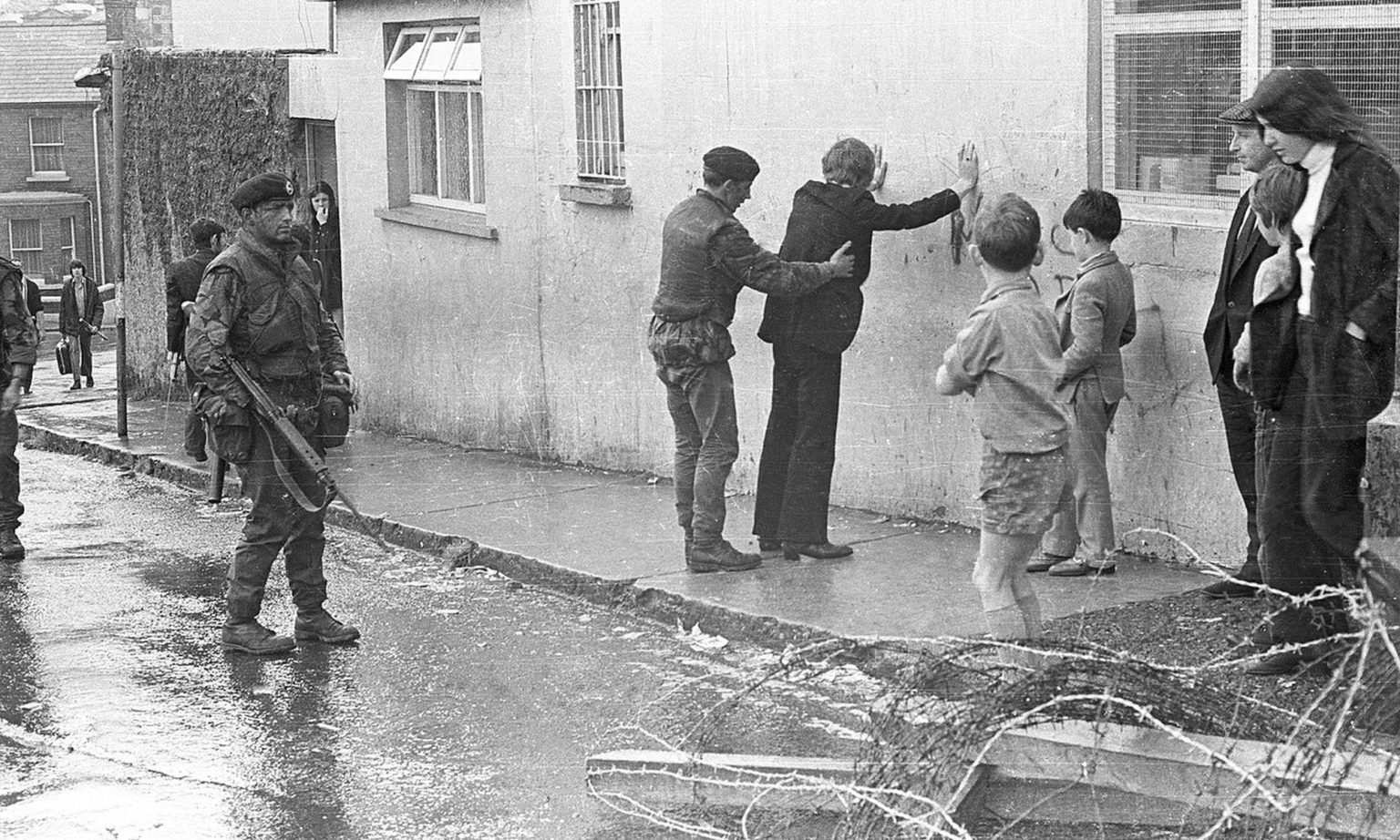

The year that followed was fraught with regular rioting and rising tensions between the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the Catholic population. ‘The RUC were the armed wing of the Unionist party’, says Eamon, and their actions were often flagrantly sectarian. The activist and journalist Nell McCafferty recalls a time when the RUC ‘went on a midnight rampage’ through the Bogside, ‘breaking doors and windows’. Such illegal activities by the police, combined with an opportunistic IRA which depended on local grievances for the purposes of recruitment, meant that conflict became inevitable.

The catalyst was the Apprentice Boys march, which takes place in Derry every year on 12 August to commemorate the 1689 Siege of Derry, in which the Protestants within the city walls successfully held out against the Catholic forces of King James II. Fifteen-thousand Orangemen would be marching past the Bogside, just a month after the 12 July parades, at which members of the RUC joined in with sectarian rioting by throwing stones. After almost a year of continual civil disruption since the NICRA march on 5 October, the atmosphere had most definitely soured.

‘What you’ve got to understand about the Orange Order’, says Eamon, ‘is that some of these marches were manifestations of triumphalism. And they were going to be protected. The police sealed off the Bogside to protect the Orangemen. The flash point was at the end of William Street. Had the Apprentice Boys changed the route, the mayhem may not have happened.’

There is a fascinating booklet of photographs created by the Bogside Republican Appeal Fund, available online at Ulster University’s CAIN website, which records the dramatic events that unfolded at the Battle of the Bogside, interspersed with captions that show the characteristic gallows humour of those who lived through the worst of the Troubles. One image shows members of the RUC charging into the Bogside with local Protestants in civilian clothes. There can be little doubt that a sectarian alliance was taking place. ‘On the 12th the RUC attacked the Bogside’, says Eamon. ‘They had the B-Specials as a backup [a reserve force which was finally dispatched on the third day]. They were all in masks and had batons. A number of people in civilian clothes attacked the Bogside and none of them was arrested. I thought to myself, we’re going to have fatalities.’

By this point, Eamon had already been running his pirate ‘Radio Free Derry’ from his house in the Creggan, but as the trouble in the Bogside escalated he decided to temporarily relocate to the top of the Rossville Flats at the heart of the disturbances. ‘It was to try to get people to erect barricades and defend them and stay on their own side’, he says. ‘I didn’t have much hope of it working, but I felt obliged to try.’

‘The fighting went on through the day and night’, he adds. ‘Some were throwing petrol bombs from the top of the Rossville Flats at the end facing William Street. I was based at the other end. I remember two guys bursting into the wee room, breathless, saying that the city engineer had threatened to turn off the water to the Bogside. So I went on the radio and said to the city engineer that if he turned the water off we would turn off the gas supply to the whole of Derry. The gasworks were on our side of the barricades, you see.’

I mention to Eamon a prominent mural on one of the gables in the Bogside, which to this day depicts a young Bernadette Devlin (a civil-rights activist who was to become an MP) rallying the residents through a loudspeaker. She was later convicted for inciting violence and served a prison sentence. Was she or anyone else co-ordinating the defence of the Bogside against the RUC? ‘No’, says Eamon. ‘It was mayhem. There were no strings being pulled. The only people who were in any way organised on the day were the IRA, but they were there to increase their membership. No one could control it.’

Eamon is doubtless referring to the IRA men, led by veteran Sean Keenan, who had set up the Derry Citizens Defence Association and encouraged the local population to prepare by gathering materials for barricades and petrol bombs. According to journalist Peter Taylor, there had been very few empty milk bottles returned to the dairy in the days leading up to the conflict. When the police stormed into the Bogside, the locals were ready to take them on. The fighting became so intense that, for the first time in the United Kingdom, CS gas was used for the purposes of riot control.

‘After 48 hours I was convinced that the police would lose patience and kill a number of Catholics’, Eamon tells me. ‘And I had heard a rumour that a number of senior officers in the Irish army wanted to bring troops to the north, with or without authorisation.’ Loyalists also believed that there was to be an imminent invasion by the Irish army. The taoiseach, Jack Lynch, had made an inflammatory statement on television, claiming that ‘the reunification of the national territory can provide the only permanent solution for the problem’, and that army field hospitals had been established in Donegal, just over the border. If anything was going to provoke the kind of disproportionate reaction from the police that Eamon feared, this was it.

‘So, on Radio Free Derry, I called for the British troops to be put on the streets’, Eamon says. ‘I had suggested it before at a public meeting and lost some of my friends because of that. But I realised that if the British troops came on the streets, Britain would have to assume responsibility. They’d realise that the system was so bad and so corrupt and so evil that it would have to be replaced.’

It would be almost 38 years before the British army finally left Northern Ireland. Many of Eamon’s photographs of the period, often taken at great personal risk, are collected in his book, Derry: The Troubled Years, and on the CAIN website. They include a number of images taken during the massacre on Bloody Sunday on 30 January 1972, when British paratroopers shot 28 unarmed civilians, killing 14. As a man who has had 11 children and fostered a further 15, Eamon clearly has an investment in the future, but is dismayed by the idea that so many should think that violence is the most effective route to progress. Although a fervent supporter of a United Ireland, Eamon has always promoted the ballot box over the Armalite. He describes the Provisional IRA as those ‘whose hands are dyed indelibly with the blood of innocent people’.

Last year, Eamon joined a ‘walk of atonement’ with others who had attended the march he had organised with Eamonn McCann on 5 October 1968. They retraced the original route as a memorial to the 3,500 people who died in the Troubles that followed. ‘The price we paid was horrendous’, Eamon said to the Irish News last year. ‘It’s a price that never should have had to be paid.’ Although he now believes that events such as the Battle of the Bogside were necessary to bring about the collapse of Stormont, he still maintains that the people of Derry should never have been compelled to resort to violence. ‘If the state had treated all of its citizens equally’, he insists, ‘none of this would have happened’.

Andrew Doyle is a stand-up comedian and spiked columnist. His book Woke: A Guide to Social Justice (written by his alter-ego Titania McGrath) is available on Amazon.

Header picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.