The labour movement has turned against the working class

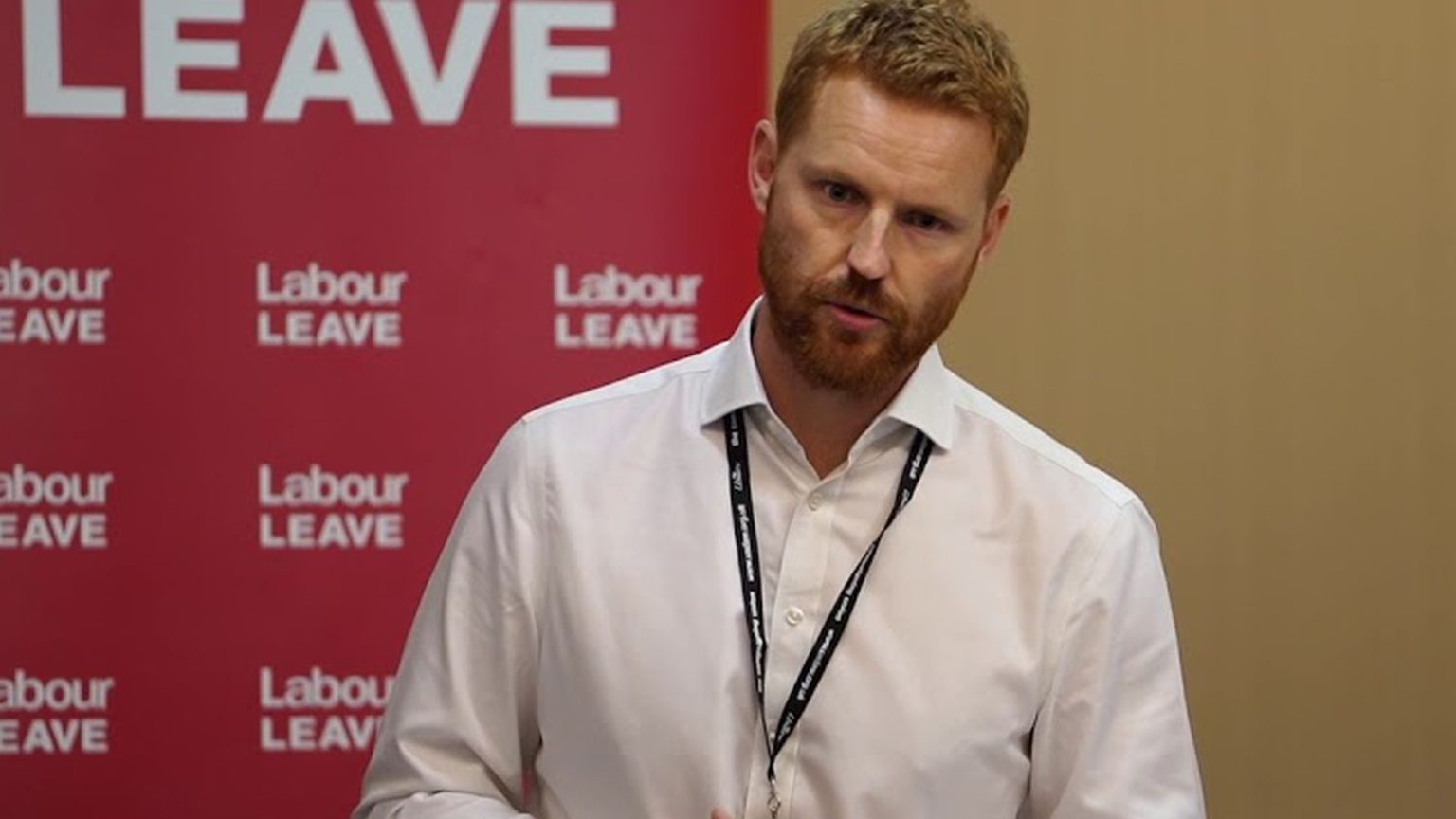

Paul Embery on Brexit and the cultural chasm between the left and the working classes.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Trade unionist and vocal Brexit supporter Paul Embery has been asked to cease using social media by his union, the Fire Brigades Union, after making comments which described Britain’s pro-Remain middle classes as ‘rootless’ and ‘cosmopolitan’. He was accused of referencing an anti-Semitic trope by prominent figures on the left, including Labour MPs Clive Lewis, Paul Sweeney and Alex Sobel. Embery was also attacked for speaking in favour of Brexit at the recent March to Leave in Parliament Square. Around the same time, many on the left were viciously denouncing RMT trade unionist Eddie Dempsey for his Brexit stance.

These rows seem to encapsulate a sharp divide within the Labour Party: between working-class, pro-Leave trade unionists and many of the party’s liberal, metropolitan, pro-Remain activists. spiked caught up with an unrepentant Paul Embery to talk about his remarks, the trade-union movement, and the future of Labour.

spiked: What were you trying to get across with your comments about a ‘rootless’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ middle class?

Paul Embery: It all started with a tweet from Gary Lineker. He said that he found it ‘baffling’ that people could see any benefit in ending freedom of movement post-Brexit. I then responded by asking, does he share his house keys with everyone on the street, or does he only ever enter other people’s homes when invited? That then stimulated a bit of online discussion. Mike Harding, the folk singer, who I remember watching on TV when I was a kid, came back and said ‘a nation is not a home’. This struck me as something that he and others might believe, but millions of ordinary people don’t.

This really captures the divide in our society, as I tweeted, between ‘a rootless, cosmopolitan, bohemian middle class’ and a ‘rooted, communitarian, patriotic working class’. In my view, it was very clear that this was aimed at a particular set of middle-class liberals and how they view the idea of a nation, in comparison with working-class people, who do see their nation as a home. I thought this was a pretty straightforward point to make, even if people disagreed with it.

Some of my opponents then pointed out that Stalin had once referred to Jewish intellectuals as ‘rootless cosmopolitans’ back in the 1940s. You would have to be something of an expert on communist history to know that. I didn’t know that. Lots of politically active and knowledgeable people have got in contact with me to say they didn’t know it. I’ve even had Jewish people contact me to say they didn’t know it. Whatever Stalin might have said, the discussion itself had nothing to do with Jews or Jewishness, and so it was clearly not an attack on Jewish people in any way, shape or form.

It was Twitter at its pitchfork-wielding worst – a classic example of people going out of their way to be offended by something that wasn’t offensive. The people attacking me were looking to take a free kick over things they disagree with me over anyway, whether it’s Brexit, my Blue Labour politics or my stance on free movement. And I have no desire to apologise. First, because I’ve done nothing wrong. Second, because an apology is never enough for these self-appointed censors. They will always demand more. You should only apologise if you are at fault for something, not because someone has decided to take offence at an innocent use of words. These scarlet-faced witch-finders are a threat to free speech, and they need to be faced down remorselessly.

spiked: You were also attacked for speaking at the March to Leave. Why was that?

Embery: The March to Leave was a cross-party rally, with speakers from left and right, that attracted thousands of people, many of them ordinary working-class people, even some trade unionists. It was a pro-democracy rally. My view is that the principle of democracy is under threat. If you look at the way the establishment has tried to obstruct the biggest democratic mandate in our history, then you cannot but come to the conclusion that democracy itself is under pressure in a way we haven’t seen before.

I don’t by any stretch agree with all of the people speaking at the rally. But I wanted to take the opportunity, as someone from the left and the trade-union movement, to speak to thousands of ordinary working-class voters, many of whom had never been on a demo before, to talk about defending democracy and Brexit from a left perspective. If that meant breathing the same air as people I disagree with on some issues, then that was something I was willing to do.

Interestingly, the People’s Vote campaign had a rally earlier this week and people from the Labour movement shared the stage with right-wing Tories. With Vince Cable… a collaborator with the Tory government who helped to push through austerity. It was telling that the same people who attacked me for speaking at the March to Leave were silent about this.

The working-class people at the pro-democracy March to Leave should be the target audience for the trade-union movement. Sadly, the left and the trade-union movement are siding with the establishment against the majority, when those people used their Leave vote to hit back at the establishment. The left has to start asking itself some serious questions as to why so many working-class people feel alienated from them. But it’s not hard to work out the answer.

spiked: How has this distance come about?

Embery: There is a chasm between the leadership of the trade-union movement and working-class people. The trade unions have effectively retreated to their public-sector comfort zone. They have very little influence in the private sector. Once upon a time, the unions were very strong in the car industry, manufacturing and heavy industry; they are almost absent now.

Of course, that’s partly down to de-industrialisation. But there has also been a political shift within the leadership of the unions. It’s more London-centric. It’s much more a part of that liberal, middle-class club that is obsessed with identity politics but less interested in the bread-and-butter issues, like pay, that affect millions of union members up and down the country.

We live in a time when unions are needed more than ever. We have zero-hours contracts, the gig economy, transient employment, sweatshop warehouses with the kind of abuses you would get in the Victorian days. But the trade unions are just not there. I think the leadership of the trade-union movement – as exemplified in the Brexit debate – is in a completely different place to ordinary working-class people.

spiked: Have there been similar trends in the Labour Party?

Embery: The Labour Party now is increasingly a bourgeois, metropolitan, liberal party. It is obsessed with students and youth. It’s very London-centric – removed almost completely from parts of this country, such as the northern industrial heartlands, where the Labour Party was once a strong presence.

Over the past 30 years, Labour has shed the pretence of being an avowedly working-class party and has become this middle-class liberal party. It thought that because working-class people wouldn’t have anywhere else to go, that they would always keep those voters on board. But I think recently – and Brexit has contributed to this – those voters no longer feel the tribal loyalty to Labour that they once did.

In the 2017 election, we saw a swing from Labour to the Tories in some of those old, working-class heartlands. We lost seats like Mansfield, Walsall North, Stoke-on-Trent South and Derbyshire North East – an old mining constituency. The polling since the election has shown that the Tories won more support among C2DEs, the occupational working class. These are really scary statistics for a party that claims to be on the side of the working class. But Labour is not asking itself why so many people feel no sense of belonging within the party. Some people feel that Labour doesn’t even want their vote anymore. Whether it is Gillian Duffy or the white-van man in Rochester with the England flag, who Emily Thornberry thought was some sort of museum piece, unless we start making those people welcome in the party or treat them as people we are proud to represent rather than as embarrassing elderly relatives, then we’re not going to win them back.

Paul Embery was speaking to Fraser Myers.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.