We need a new bohemianism

Sexuality and rebellion have been co-opted by capitalists.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Bohemianism, though hard to define, can at least partly be characterised as the fusion of radical creativity and sexual emancipation. Throughout history, it has been an engine for social progress, as artists and free thinkers sought to challenge the petty orthodoxies of their times.

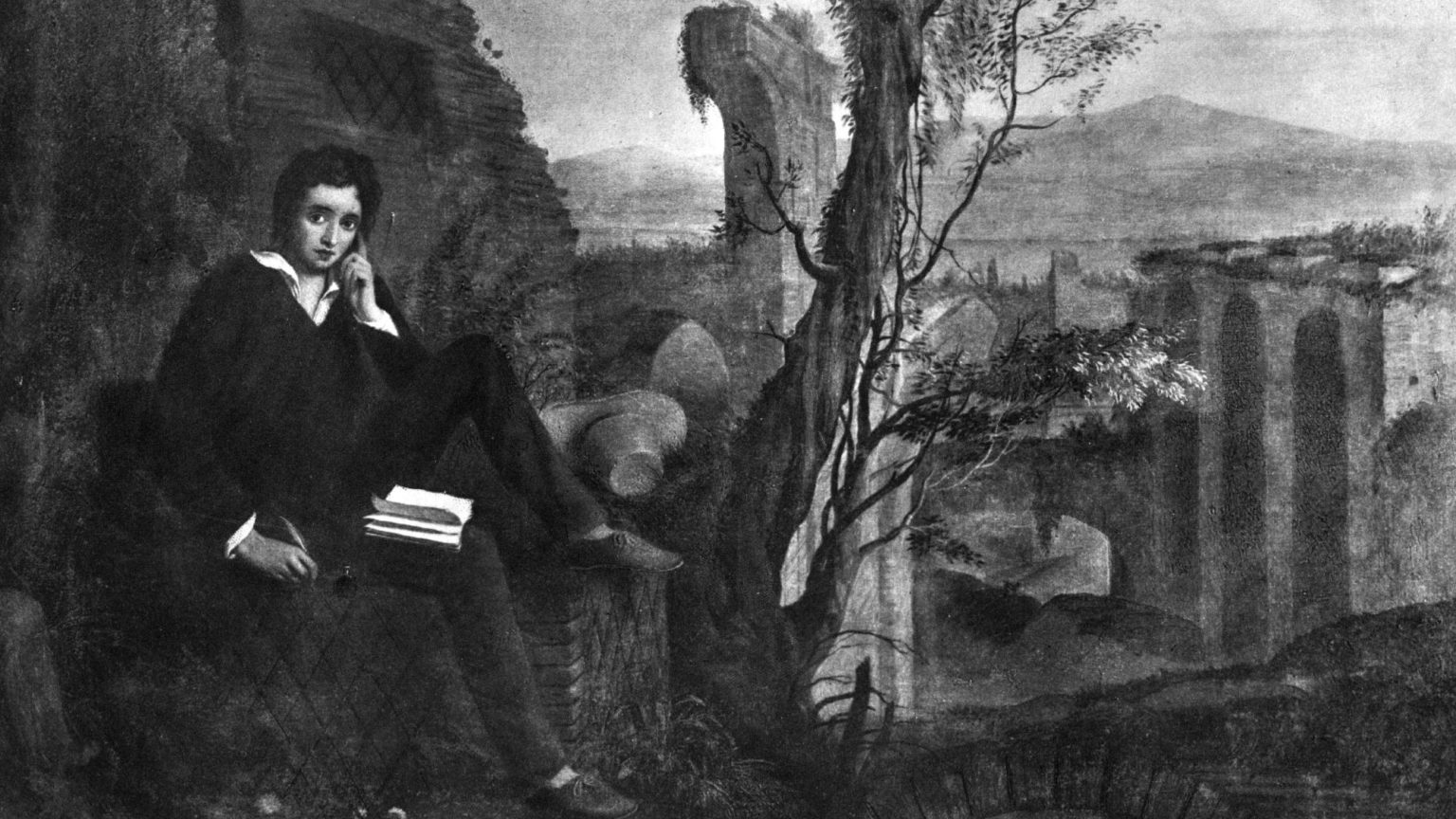

In the early 19th century, Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was a pioneer of sexual freedom. He opposed what were then the stale, misogynistic rituals of marriage. He pursued a life of pagan spirituality, vegetarianism and free love. He travelled across Europe with his soulmate, novelist Mary Shelley. Percy Shelley led the way for countless rebels and free spirits to come.

In Britain in the early 20th century, the Bloomsbury Group pursued a life devoted to sensual freedom, challenging the gender roles that stifled sexual politics. Radical pleasure-seeking was also at the heart of the Beat Generation, a group of writers in mid-20th century America, who created a new literature based on wild, ecstatic experiences and the unshackled pursuit of sensual liberation. The closest thing this movement had to a manifesto was Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, which deploys imagery of gay sex and drug-taking to articulate the flight of the modern soul from America’s suburban decay. Drawing from William Blake’s visionary credo, that ‘the path of excess leads to the palace of wisdom’, the counterculture of the Sixties followed on from the Romantics, Bloomsbury bohemians and the Beats, using sexual license and hedonistic joy as a spur for political and cultural change. We still live in the shadow of these bohemian breakthroughs.

But something has gone badly wrong since. Today the pursuit of pleasure all too often becomes a form of addiction and self-enslavement, whether it is to brand consumerism, social media or online porn. We are perpetually bombarded with temptations to follow through on our bodily desires. Sex is relentlessly foisted on us by the media and advertisers, who seek nothing but our captive attention and the secrets of our purchasing habits. Images of beautiful hipsters and curved-bottomed celebrities cajole us into giving up our personal agency for the promise of pleasure and satisfaction.

Even rebellion itself is now a Trojan horse for corporate marketing. Think of Pepsi’s ill-judged Kendall Jenner advert, which sought to piggy-back on social-justice protest culture. Or more recently, Smirnoff’s bid to sell drinks on the back of International Women’s Day. Perhaps the starkest example of this corporate co-option of radicalism dates back to Apple’s Superbowl advert in 1984. A youthful, sportswear-clad model smashes the image of George Orwell’s Big Brother in order to advertise the new Macintosh computer.

People often compare George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and ask which writer’s dystopian vision was the most prophetic. Journalist Thomas E Ricks says that this question is based on a false antithesis. He argues that both writers understood the perilous way that pleasure could be used to manipulate people into compliance and standardised behaviour. As Orwell wrote in Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness. And for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better’.

The response to Orwell’s worrying suggestion should not be a reactionary puritanism. This is one potential danger of the movement around Jordan Peterson and the rise of YouTube conservatism. While today’s cultural consensus is worthy of critique, there is little positive about returning to either a knee-jerk Victorianism or a 1950s culture of routine and stifled obedience.

Instead, we need to reclaim a more creative, self-reflective and discerning relationship with our senses and desires. Shelley’s belief in the transformative power of sexual freedom and pleasure almost certainly came from his understanding of Plato’s Symposium, a dialogue which venerated sex, beauty and homosexuality as being paths to spiritual knowledge.

Today’s drab identitarians, on the other hand, believe that by expressing themselves with new genders, sexualities and victim identities, they are challenging dominant power structures. But more often than not, these activists are merely conforming with the times.

The missing ingredient here is the soul. The genuine sexual revolutionaries of old were driven not by a vision of political power, but by an ideal of human transcendence. The significance of pleasure was not that it made politicians and conservatives feel squeamish, but that it emancipated individuals from routine and guided them towards truth and the fulfilment of their potential.

James Black is a writer and folk singer based in London.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.