The digital communism of Mark Fisher

His up-to-now unpublished writings reveal a thinker clinging to the political potential of the internet.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

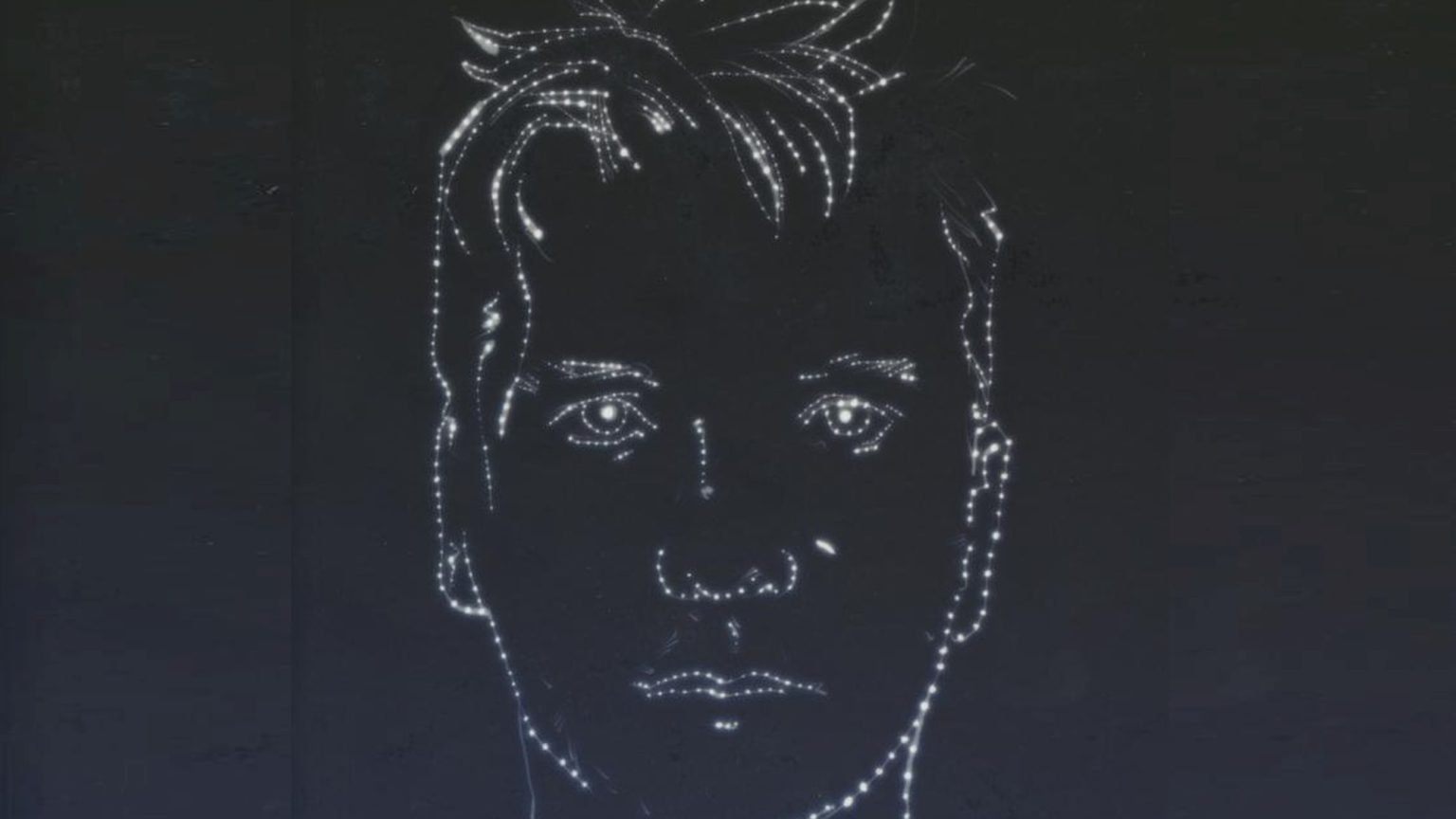

For a generation of British leftists, the ‘weirding’ of global politics was ushered in not so much by Trump’s inauguration, but by the suicide two years ago of one of the figures to whom we would otherwise look to help us make sense of it: Mark Fisher. Today, the work of this English cultural critic, musicologist and activist is posthumously sought out and pored over by new generations – both younger millennials and those in ‘Generation Z’ – for the sense, or solace, it might offer.

As such, a posthumous compendium of Fisher’s work, K-Punk: the Collected and Unpublished Writing of Mark Fisher, has a responsibility to explain not only how things once were – in the early days of internet blogging, when the internet as medium created a sense of immense hope – but how things are, and will be. Not so much because Fisher had the answers (and his modesty certainly prohibited him from ever claiming so), but because he was instrumental in the cause of an internet-fuelled redistribution of power that led the theory-blogging community of which he was part. Accordingly, it is natural that people look to Fisher to help answer the question of where to go from here – of whether to press on and see where the internet leads us, or to tame it, following its facilitation of social-media celebrity, ‘selfie dimorphism’ and the alt-right memester.

Fisher’s book is divided into seven chapters: on books, film and television, music, interviews, commentaries, and ‘acid communism’ – his last unfinished project. Across this nearly 800-page volume, a central contradiction in Fisher’s thought stands out. Namely, that while the left rightfully feels itself to be almost completely hopeless, Fisher carried on in the belief that something in society might one day yield to socialism. Arguably, it is the potential of the internet that underpins this faint positivity, leaving us to battle for its freedom, not least in light of the EU’s proposed new copyright laws, which would heavily restrict the sharing and creative appropriation of information.

Fisher was among a generation of activists who, while being aware of the limitations of the internet, saw it as somehow fundamental to the future of political discourse. In his essay ‘Aesthetic Poverty’, Fisher drew upon the London riots of August 2011 to point both to the controlling effect and emancipating potential of online communication. The riots, involving looting, vandalism and arson, were initially a response to the police killing of 29-year-old Mark Duggan, of Irish and West Indian descent. But then UK prime minister David Cameron was quick to denounce the unrest as apolitical ‘thuggery’. The mainstream media concurred, pointing to the rioters’ possession of smartphones, which aided the organisation of their pillage, to reinforce Cameron’s assertion that the rioters were not impoverished opponents of the status quo.

However, as Fisher pointed out, smartphones and access to social media are less an expensive optional extra, than a necessary part of a modern individual’s way of life:

‘Paying for an interface into the communicative matrix is more like paying for one’s own tools at work than it is like buying a luxury good. The very distinction between work and nonwork, between entertainment and labour, erodes.’

As such, the rioter’s possession and use of smartphones was more a sign of their lack of agency than of their material wealth – a lack shared by most of society. Though beyond this, Fisher hinted at the capacity for smartphone and social-media technology to bring people together:

‘While the riots in England could hardly be said to be a coherent political statement, in this collective use of social media there was perhaps the beginnings of something like class consciousness. And in the destruction of the depressing facades of corporate retail, is it too fanciful to see a rejection of the aesthetic poverty that corporate capitalism imposes on so many of us?’

* * *

Fisher’s suicide took place a little over six months after the Brexit referendum and just one week before Trump’s inauguration, though the unfinished text ‘Mannequin Challenge’ captures perfectly the farcical aspect of today’s politics. The piece, ‘K-punk’s final unfinished and unpublished post’, takes its title from an online video of Hillary Clinton and her campaign team performing the ‘mannequin challenge’, a viral trend whereby groups of people filmed themselves in frozen poses, as the camera moves around them. As Fisher argued, it was not only Clinton’s smug grin that caused discomfort, but its closeness to reality:

‘This simulation of stasis – reminiscent of the eerie scenes in Westworld in which the android-hosts are temporarily put into sleep-mode – actually revealed what the Clinton campaign was composed of: decommissioned political robots playing out an exhausted programme one last time before being permanently taken offline.’

The problem with the centre-left, Fisher argued, was that its members fail to capitalise on discontent, while Trump and Brexit succeed in doing so, playing to the house: a fantastic absurdist theatre that spoke to people’s dissatisfaction with reality. The left has yet to match this act, or even to understand its mechanisms, preferring to admonish the recalcitrant working class for not voting as it apparently ought to. Above all, the left today fails to understand that movements are not made, formed, cajoled and patronised into action by politicians, but rather ridden bareback, and it is Trump’s and other populists’ ability to ride, rodeo-style, the discontent of the working class that has ensured their success. With European elections approaching in May, Brexit a parliamentary shambles and the Democratic caucuses opening this year, the left would do well to take the pulse of the disaffected working class, rather than trying to lead from the moral high ground.

Though perhaps all is not lost, and Fisher was fundamentally a believer in the power of collective action. This belief left him dismayed at the online left and its constant in-fighting. As such, though barely necessary given its diffusion online, the volume’s inclusion of his 2013 text, ‘Exiting the Vampire Castle’, serves to underscore a vital message for our time. It addresses the rise of the identitarian left, and ‘that moment when the struggle not to be defined by identitarian categories became the quest to have “identities” recognised by a bourgeois big Other’. Identity politics, Fisher argued, ended up doing the divisive work of capitalism on its behalf, as suddenly leftist kudos was to be gained not by one’s connection to – or resuscitation of – the community, but by one’s separation from it, as an individual with specific grievances (whether linked to race, gender, sexual orientation, etc). Accordingly, one could argue that the left has been co-opted by the individuating, atomising right, finally laying waste to the hope that a sense of community might emerge out of and in opposition to capital. Which it won’t, so long as the highest accolade of the left is that of a particular identity recognised.

It is for this reason that Fisher turned to his final and unfinished project, ‘Acid Communism’ – the introduction of which closes this volume of collected writings. As a sketch and indication of what he may have gone on to finish, it points to some small possibility that the left can regain hope by revisiting the wide-eyed dream states of its 1960s and 1970s forebears. Writing in the midst of the depression that scarred his life, Fisher drew strength from a nostalgia for an era when people experienced a love – channeled via music – that was both ‘collective and oriented towards the outside’. He felt that the only possible solution to our societal malaise resides in a fantasised new world that might one day spill over into reality. As Fisher points out at the end of his introduction, the material-communicative conditions necessary for community to flourish have never been more ripe than today (he was writing in 2016).

Upon reading this, I felt that ‘Acid Communism’ could have been called ‘Internet’ or ‘Digital Communism’, and that Fisher retained his hope for the potential of new media communications even in his last days. It seems the battle for the internet was as crucial for Fisher as it ought to be for us.

Mike Watson is an art theorist and curator. He is the author of Towards a Conceptual Militancy, published by Zero Books. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).) His new book, Can The Left Learn to Meme?: Adorno, Video Gaming, and Stranger Things, will be published later this year.

K-Punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher, by Mark Fisher, is published by Repeater. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.