Long-read

The chilling legacy of the Rushdie affair

The fatwa against The Satanic Verses author marked the beginning of an intolerant era.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

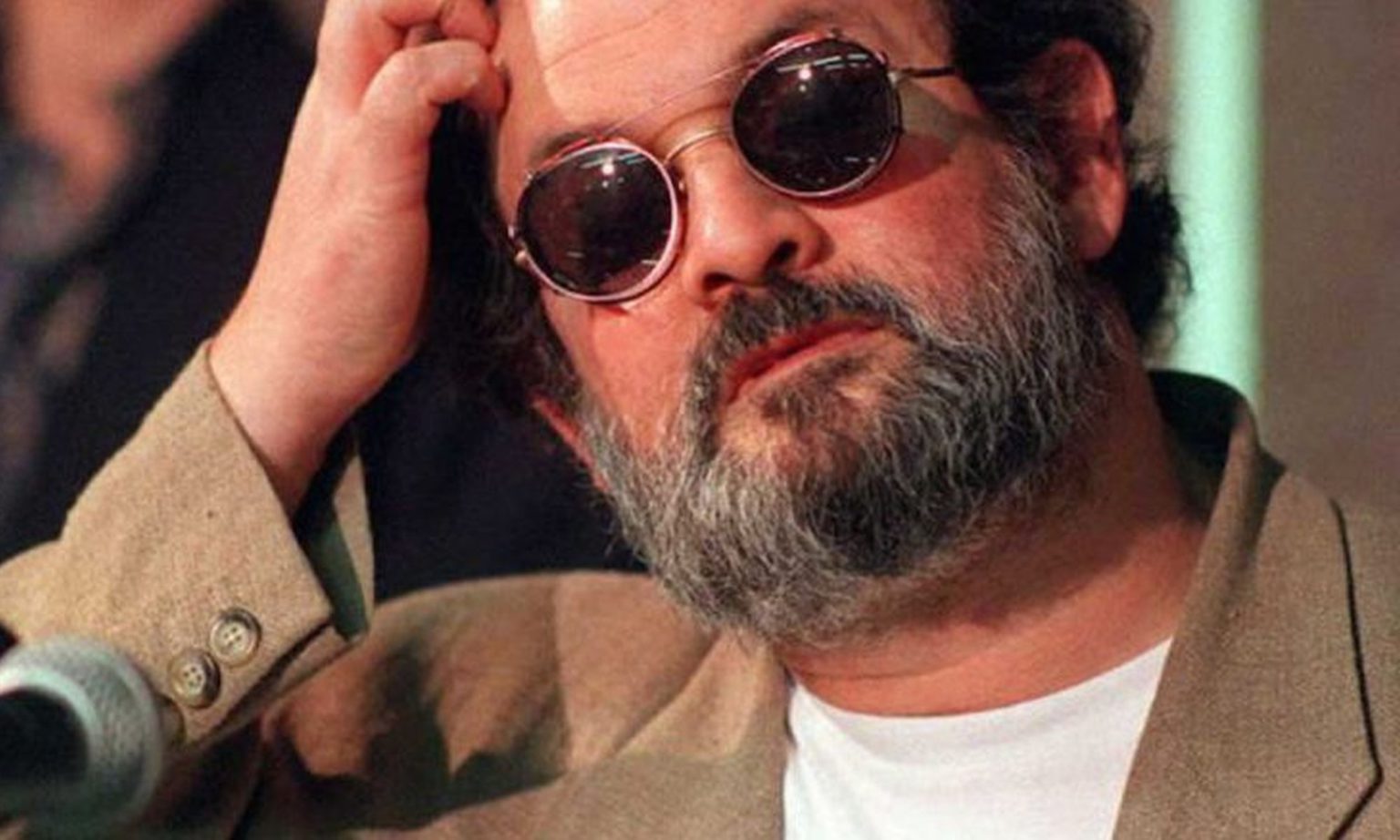

Today, 30 years after the infamous fatwa and 20 years after its de facto withdrawal, Salman Rushdie has moved on, or so he says. Asked, as he invariably is, about the episode that caused a global upheaval and sent him into hiding for a decade, he expresses resigned exasperation and changes the subject. ‘It feels like ancient history to me’, he told an interviewer in 2018, while promoting his latest novel, The Golden House. He expresses satisfaction in finding that at long last, a generation on, The Satanic Verses can be read as a novel, rather than as a controversy, a symbol, a casus belli. ‘Now, after all this time, it’s finally been able to have the ordinary life of a book’, he said in March of 2018.

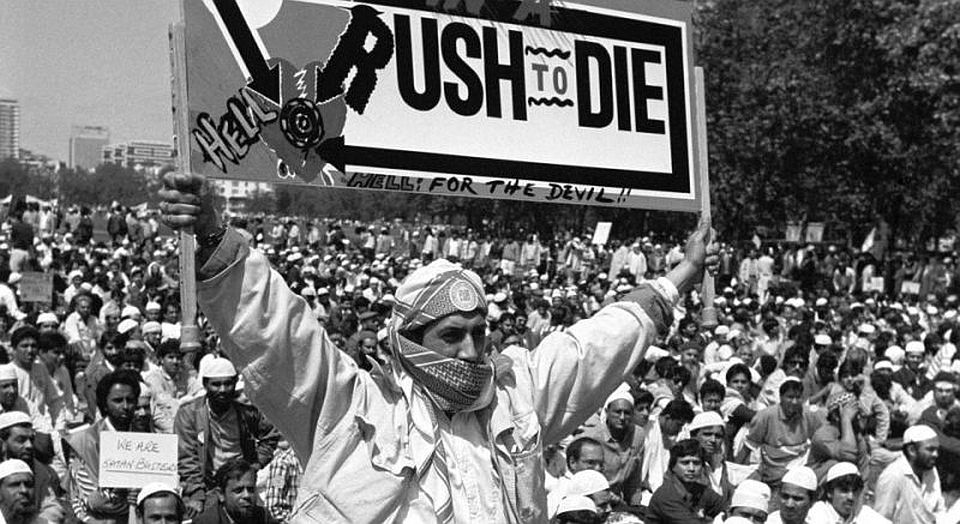

When he published The Satanic Verses in 1988, at the age of 41, he regarded it as among the least political of his works. Though he was a lauded figure in literary circles, he was not a celebrity. But in the weeks following the book’s publication, Muslim protests and threats swelled in Britain (Rushie’s home country) and abroad. On 14 February 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s supreme leader, saw a Pakistani protest on TV and issued an edict declaring the book to be against Islam and calling on Muslims everywhere to murder Rushdie and anyone who had assisted in the book’s publication.

In the nightmarish eruption that ensued, dozens of people were killed, including the book’s Japanese translator, and many more were threatened. With Iran’s multimillion-dollar bounty on his head, Rushdie was forced into hiding, under heavy guard, for nine years. In that time, his marriage failed and his output declined. Echoes still reverberate; just this past October, Norwegian police filed charges in the shooting of William Nygaard, the publisher of the Norwegian edition, who was left for dead outside his home (but survived).

At the time, many observers, myself included, believed the incident to be some kind of inflection point – a view which proved correct. But what sort of inflection point? Thirty years have brought additional clarity, and an ominous development. Today, mob demands for censorship and censure are so common they have acquired a new name: call-out culture. Contra Rushdie, the episode is not ancient history, not at all.

Mini-Rushdie affairs – ritualised denunciations that have more to do with the mob’s display of tribal solidarity than with anything the target said or did – now happen in academia and on social media every day

The Rushdie affair was hardly the first incident of terrorism committed against Western targets by Islamists, or in the name of Islam or of associated political causes. Not four years prior, Leon Klinghoffer, a wheelchair-bound American Jew aboard the cruise ship Achille Lauro, had been shot and thrown overboard by Palestinian hijackers, an atrocity that shocked the world. Even so, in 1989 the Rushdie edict was rightly understood as a paradigm shift. For one thing, it was state-sponsored. Khomeini not only called for multiple assassinations, he put his government’s imprimatur and treasury behind his decree.

Further, the attack was global in scope and ambition. By seeking to mobilise Islamist sympathisers everywhere, and by declaring publishers and editors and translators and bookstores to be targets, Khomeini declared borders to be of no consequence. Henceforth, the battlefield had no boundaries. In 1996 and 1998, when Osama bin Laden declared a global war on the United States, Israel, the West and their allies, he was following the path Khomeini had blazed.

If those aspects of the conflict were extraordinary, another aspect has become, in the intervening years, quite common. The Rushdie affair debuted what has become known as call-out culture. Anyone can at any time become the target of mass denunciation and ad hominem harassment for saying, well, almost anything.

In declaring blasphemy to be a capital offence, punishable everywhere, Khomeini’s fatwa harkened back to religious medievalism. Even at its most abusive, however, the Inquisition took ideas seriously. It scrutinised heresies and interrogated heretics, and it offered its victims the opportunity to repent and retract. But Rushdie’s antagonists did nothing of the kind. To the contrary, they showed little if any interest in what Rushdie had actually written, or in what he believed. Hardly any had read the book, a challenging novel about immigration and identity. ‘Precious few… even bothered to read extracts’, wrote Daniel Pipes, in his 1990 book about the incident. Many bragged about not reading it. ‘I do not have to wade through a filthy drain to know what filth is’, a Muslim member of India’s parliament said, supporting a ban on the book. In some sense, the book was beside the point. Purity was the point.

In his 2012 book The Righteous Mind, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt identifies sanctity as being among five moral ‘tastes’ that are fundamental to human relations. Making common cause around sacred beliefs bonds humans into tribes, which further cement their solidarity by rallying against outsiders and impurities. Millions of the fatwa’s supporters were acting not in the capacity of critics or ideologues, but in the capacity of tribe members, seeking to outdo each other in their displays of loyalty to the group. Once they had identified Rushdie as a profanation, his book might as well have been the Boston telephone directory, for all anyone cared.

The Rushdie incident was a beginning, not an end. In much the same way that the Columbine High School massacre of 1999 became a template for subsequent school shootings, the Rushdie affair became a template for global intellectual terrorism. In 2005, an eruption over cartoons of Muhammad in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten left hundreds dead. In 2010, in response to threats after she launched an ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad Day’ in support of artists menaced by Islamist violence, the American cartoonist Molly Norris was threatened with death and driven into hiding, where she remained for years. In 2011 and again in 2015, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo was attacked by terrorists in response to Muhammad cartoons; in the second attack, 12 were killed (including the publisher) and 11 more injured.

The broader, less spectacular result of the Rushdie affair has been to chill thought and expression everywhere. ‘For every exercise in free speech since 1989, such as the Danish Muhammad cartoons or the no-holds-barred studies of Islam published by Prometheus Books’, Pipes wrote in 2010, ‘uncountable legions of writers, publishers, and illustrators have shied away from expressing themselves’. Today, we know that the Rushdie affair, though unique, debuted a quite successful business model. Rushdie may be free, but the shadow of the fatwa lingers.

In a notorious incident in 2017, students at Middlebury College shouted down a talk by the conservative scholar Charles Murray, and then a group of protesters (which included both outsiders and students) physically attacked him and a faculty member, giving her a concussion. The ostensible reason for the protests was Murray’s controversial 1994 book The Bell Curve, but few if any of the students had read the book, and their ritualistic denunciation and expulsion of Murray had elements of a religious revival and exorcism. Observers such as Haidt and the commentator Andrew Sullivan have pointed out the religious overtones of politically correct displays of outrage and demands for purity. Solidarity and sanctity, not inquiry and argument, are the point.

On campuses and online, variants of the ‘calling out’ phenomenon – ritualised mass denunciations of supposedly intolerable offenders – have become routine. In 2017, when Rebecca Tuvel, a philosopher at Rhodes College, published an academic article comparing transgenderism and transracialism, she was denounced by over 800 academics in an open letter. Writing in New York Magazine, Jesse Singal found that the letter had blatantly mischaracterised Tuvel’s article. ‘Either the authors simply lied about the article’s contents, or they didn’t read it at all.’ In January, Singal reports, a first-time novelist named Amélie Wen Zhao withdrew her book before publication under pressure from an angry online mob of self-appointed social-justice monitors, most of whom had not read the (still unpublished) book they were censuring. Mini-Rushdie affairs – ritualised, often randomly triggered denunciations that have more to do with the mob’s display of tribal solidarity than with anything the target actually said or did – now happen in academia and on social media every day.

I am not suggesting that politically correct pile-ons are the same as state-sponsored death threats. Nor am I claiming any causal connection between the Rushdie affair and, say, the Middlebury affair or the Tuvel call-out. My claim is only this: that the impulse to rally against blasphemy and to drive out impurity is a human impulse, not a radical or Islamist or specifically religious impulse; and that lots of sophisticated people in places like America and the UK are yielding to it; and the ultimate consequences are barbaric and oppressive, because of the victims they destroy and the conversations they squelch.

Writing in the New York Times, Laura Gianino recalled approaching Rushdie at a social function. ‘The Satanic Verses changed my life’, she told him. ‘Well, that’s good’, Rushdie replied, ‘because it ruined mine’

No one can begrudge Rushdie his desire to move on. He set out to be an author, not a hero. Writing in the New York Times, Laura Gianino related how, as an awestruck editorial assistant, she approached Rushdie at a social function. ‘The Satanic Verses changed my life’, she told him. ‘Well, that’s good’, Rushdie replied, ‘because it ruined mine’.

So let us grant Rushdie the right to his bygones. Yet let us also recognise that he is, in actual fact, a hero. With the exception of one brief and desperate faltering, Rushdie understood the principle he had been conscripted to represent, and he stood firm for it. ‘What is freedom of expression?’, he famously said. ‘Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.’ In 1995, still in hiding and under 24-hour guard, he surfaced to say this: ‘If someone is trying to silence me, then I should find a way of speaking back with increased force. If someone is trying to subject me to an attack of what you might call hatred, then I should not return hatred for that hatred. I should try to return instead all the generosity and openness of heart that is possible through literature and art.’ These are the words I hope – but do not expect – I might have the courage to say if I were ever tested.

Though Rushdie now lives openly and without armed guards, he remains under threat. In 2005 Iran’s supreme leader said that the fatwa remained valid, and in 2016 a group of hardline Iranian news organisations topped up his bounty. In 2015, Iran responded with an angry boycott when the Frankfurt book fair engaged Rushdie for a keynote speech. Yet there he was, saying that ‘limiting freedom of expression is not just censorship, it is also an assault on human nature’, and that ‘without that freedom of expression, all other freedoms fail’. Rushdie, under unimaginable pressure, rose to the defence of his craft and his principles. In doing so, he showed us the stakes and clarified the choices, and he put his detractors to shame.

In my 1993 book Kindly Inquisitors, I likened the Rushdie affair to a lightning strike which illuminated a darkened landscape and revealed a defining question. Do we, as individuals, and as a society, stand with Rushdie and the right to offend? Or are we finding exceptions, making excuses, calling out, piling on? Thirty years on, the question remains open.

Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, a contributing editor of the Atlantic, and the author of six books including: Kindly Inquisitors: The New Attacks on Free Thought; and, most recently, The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50.

Picture by: Getty Images

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.