Why we mourn Albert Finney

His death reminds us of the failure of Britain’s progressive promise.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

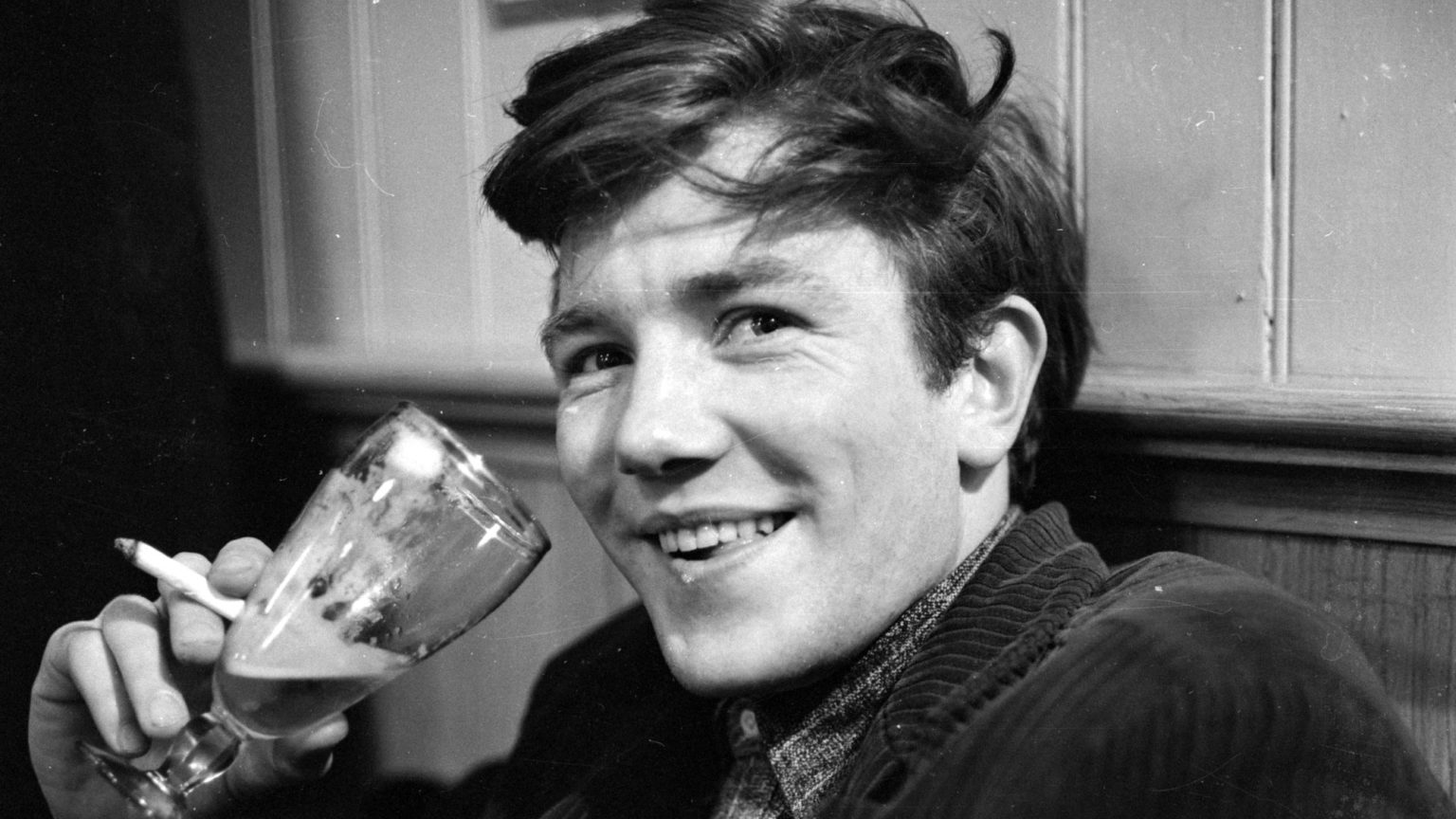

The national sorrow over the death of Albert Finney – ‘Saturday night and Sunday mourning’, as the Sun described it – is about more than the passing of a great actor and celluloid icon. People also seem to be lamenting the passing of an era. We seem not only moved by the end of Finney’s rich and colourful life, but also reminded of a time when people like him, pretty ordinary people, could rise to great cultural heights. Finney’s death has struck a chord because the promise he so brilliantly represented – the promise of egalitarianism, the promise of talent, the promise of people from the lower classes using their swagger and skill to take their place alongside anyone from the silver-spoon set – has faded. And faded badly.

Witness the somewhat guilt-infused nostalgia in many of the broadsheet lamentations for Finney. Images from his breakthrough, and arguably most famous, role – in Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) – adorn newspaper spreads. Finney played Arthur Seaton, a hard-working, hard-drinking, hard-screwing factoryhand and angry young man, in this adaptation of Alan Sillitoe’s explosive 1958 novel. As many observers have noted, his turn as Seaton heralded the arrival not only of honest depictions of working-class life in British cinema, and not only of this young muscular actor from Salford, but also of a new cultural age. One in which a confident, educated working class might finally do what once only the moneyed or middle classes had done: star in movies, write novels, do Shakespeare, go to RADA, make music. And in much of the Finney commentary there has been a muted recognition that this doesn’t happen that much anymore; that maybe even Finney himself wouldn’t have made it today.

Of course, much of the focus is on Finney’s cultural achievements, and rightly so. His Seaton was a finer and more intellectual distillation of the rebellious spirit of the late 1950s and early 1960s then anything James Dean or Marlon Brando managed. And he was justly proud of the edginess of this first major role, often boasting that he was the first actor in British cinema to play a character who was shown kissing another man’s wife. Later there was Tom Jones, for which he received his first of five Oscar nominations; Annie; Scrooge; the Coen brothers’ brilliant Miller’s Crossing; Dennis Potter’s disturbing Cold Lazarus (in which Finney played the cryogenically stored head of his character who died at the end of an earlier Potter drama); and a superb turn as the grouchy but warmhearted lawyer Ed Masry in Erin Brokovich. He could have been Lawrence of Arabia, too, but he turned it down.

Yet alongside what Finney did, there is also, undeniably, what he represented, what he spoke to in early 1960s Britain. He was the Salford-born son of a bookmaker. Obits describe him as working class, though he preferred to describe his background as lower middle class. Like his contemporary Tom Courtenay – star of another Sillitoe adaptation, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (1962) – Finney benefited from the old grammar-school system that allowed some members of the working and lower middle classes to get a top-notch education. Grammar school was ‘all about going up in the world’, as Courtenay once put it (while also lamenting the fact that the other 49 pupils in his class of 50 didn’t make it and were left behind. A class of 50 – ‘that shows how poor the area was’, Courtenay said.) For Finney, grammar school was also about moving up, but in a different way. He failed all of his O Levels but one – geography. Yet rather than writing young Albert off, his headmaster suggested he give RADA a whirl.

Finney, Courtenay and others were beneficiaries of a time when some sections of society had high expectations of the working class, and when they had high expectations of themselves. Of course it was a far from perfect time. The grammar-school system selected the best of the lower classes – or more accurately, those who were best at passing an exam, in this case the 11-plus – and in doing so it implicitly discarded the rest, leaving them to a less-than-admirable comp system. Indeed, the author of Finney’s most famous role – Alan Sillitoe – had a dramatically different experience to Finney. Sillitoe was raised in grinding poverty and yet he was well-read and bright. Still he failed the 11-plus. Twice. So it was the rundown comp for him, which of course he left at the age of 14, to work in a factory. Like so many others before and after him.

And yet, the imperfect egalitarian ideals of the 1950s and 1960s were at least based on a belief that the lower sections of society were as capable of intellectual focus and understanding and maybe even greatness as were the upper, entitled sections of society. Indeed, Finney’s emergence embodied the dual, conflicting feelings the postwar elite had towards the working classes. On one hand, they had a fairly new appreciation for the talent and capacity for greatness of the working classes. Witness Finney’s head pushing him to go to RADA, that poshest of acting schools, or the opening up of universities to the non-upper classes. But at the same time the postwar elites still feared the working classes and their anger and power. Especially the kind embodied by Finney in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning – a drinker and fighter and philanderer who fantasises about blowing up his factory. ‘I’m me and nobody else; and whatever people say I am, that’s what I’m not, because they don’t know a bloody thing about me’, as Finney’s Seaton says, setting the tone for the next two decades of youthful cultural rebellion.

Fast forward to 2019 and the world could not be more different. Anger, especially among young working-class males, is no longer culturally celebrated – it is treated, extinguished, referred for anger-management therapy. White working-class men are the bête noire of the liberal elite. Respectable society looks upon modern-day Arthur Seatons – cocky young blokes with ill-advised vices – as the scourge of the nation. Poorer kids are no longer challenged in schools – they’re bombarded with ideological guff about respect and diversity and lowering your own expectations in order to avoid ‘stress’. As for culture: it has been colonised, or re-colonised, rather, by the well-connected, the well-off, the pampered, the privileged. Pop music, acting, TV writing, literature, journalism – all are dominated by plummy people. Even the Labour Party has fallen to trustafarians and youthful agitators from detached houses: studies show that Labour’s membership under Jeremy Corbyn is even more ABC and bourgeois than it was under Tony Blair. If a Momentum member were to meet someone like Arthur Seaton, or even a young Albert Finney, they’d report them to officialdom for sexist behaviour and un-PC speech.

As Michael Gove said a few years ago, public-school alumni have a ‘stranglehold’ on politics, media, sport, art and much of pop. Some on the left put this down to cuts – cuts to university grants, cuts to youth clubs, cuts to libraries, etc. No doubt all of that played a role in the depressing vacation of working people from the spheres of culture and knowledge. But there is something more profound, and less tangible, at work too. Modern society’s loss of belief in ordinary people; its conviction that they aren’t really cut out for tough exams or Latin or cultural experimentation; its pitying view of these people as ill-suited to the dreaming spires of Oxford or the plummy surrounds of RADA (they’ll feel ‘left out’); its instinct to clamp down on the lower orders’ strong feelings, particularly their anger or their demand for change, as can be seen in the increasingly unhinged response of the cultural elites to the vote for Brexit – these cultural turns play a far greater role in erecting a STOP sign to ambitious working-class youths than the closure of their local am-dram club does.

Finney turned down a CBE in 1980 and a knighthood in 2000. ‘The Sir thing’, he said, ‘perpetuates one of our diseases in England, which is snobbery’. ‘I think we should all be Misters together’, he said. These fine words were an echo of the open cultural era in which he emerged, and a rebuke to the society that failed to make good on that era’s promise. Alarmingly, things have got worse. Snobbery has intensified, though it now comes in PC garb. The section of society Finney hailed from is now looked upon largely with contempt, which of course is far worse than the combination of selective patronage and political fear it was treated to when Finney was coming up. The grief over Albert Finney contains within it a bitter, unspoken recognition that Albert Finney the cultural phenomenon would not be possible today.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked and host of the spiked podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show. Subscribe to the podcast here. And find Brendan on Instagram: @burntoakboy

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.