The Euro: a mindless idea

Ashoka Mody on the arrogant delusion of the architects of the EU.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

‘It has been a little bit of a lonely effort.’ Ashoka Mody, an economics professor at Princeton University, and the former deputy director of the International Monetary Fund’s European department, is talking about EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts, his brilliant, magisterial history of the EU and the development of the Eurozone. ‘The vast majority of the European establishment’, Mody continues, ‘has either tried to ignore or to contest what it seems to me are very basic economic principles and facts’.

One can see why the European establishment might be inclined to do so. EuroTragedy is an indictment of the whole postwar European project, a meticulous, excoriating takedown of that which the European establishment holds dear. And it is also an attack on the European establishment itself, on its members’ groupthink, their delusion, their technocratic arrogance. What’s more, it comes from the IMF’s chief representative to Ireland during its bailout from the post-2008 banking crisis – someone, that is, with an inside track on the EU’s fiscal workings.

spiked spoke to Mody to find out more about his critical overview of the European project, the fatal flaws of the Eurozone, and why integration is driving European peoples apart.

spiked: Do you think you found working on EuroTragedy a lonely effort because, after Brexit and the other populist movements, the EU establishment is very defensive at the moment?

Ashoka Mody: I’m sure it plays a role. But I think that the nature of the entire project is very defensive. Think back to Robert Schuman’s declaration on 9 May 1950, which laid the ground for the European Coal and Steel Community two years later – he said that a common source of economic development must become the foundation of a European federation. This idea of the European federation was discredited very quickly, but European leaders have continued to flirt with it in different guises – ‘ever-closer union’; ‘unity in diversity’; and this particularly meaningless phrase that French president Emmanuel Macron uses called ‘European sovereignty’. The whole language is problematic and mystifying.

But most serious of all is the notion of common economic development as a basis for Europe. It was briefly true after the Treaty of Rome in 1957, which opened up the borders, but the momentum ran out within two decades. You open borders, but once they’re open, there’s not a lot more you can do. Even the gains from the so-called Single Market are very limited beyond a certain point. Every economist understands that.

On the Euro, there was never any question that it was a bad idea. Nicholas Kaldor, an economist at Cambridge University, wrote in March 1971 that a single currency was a terrible idea, both as economics and as politics. And Kaldor has been proven right time and again.

But the entire European establishment just ignores every subsequent warning from well-regarded economists, and produces defensive counternarratives. For example, I often hear that Europe needs fixed exchange rates in order to have a Single Market. Why? Germany is trading a lot with Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, which are in the Single Market, but have different currencies. These fluctuate, but the trade continues apace. You don’t need a single currency for a Single Market.

spiked: When did your critique of the European project emerge? Was it during your involvement in the Irish bailout?

Mody: When I finished at the IMF I planned to write a book on the Euro crisis. And I began writing it as an IMF economist would – what happened before the crash, the bubble, the bubble bursting, the panic, the fact it wasn’t well managed, and so on. But I soon realised that something wasn’t right here.

And so I spent two years tracing the history of the Euro, and asking the question: what brought the Euro into existence in its current form? You see, it is not just that there is a Euro. There is a Euro, which is a single currency in an incomplete monetary union, with a set of fiscal rules that are evidently economically illiterate – and nobody questions the fact that they are economically illiterate, that they lack a necessary fiscal backstop and the necessary fiscal union. So why does it exist?

That is when I started writing what is, in effect, a postwar European history, a companion, if you will, to Tony Judt’s Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. That is when I realised the Euro was not only a bad economic idea, it was also a bad political idea. Not only was it clear it would cause political divisions, there was also no plan on how to heal those divisions, to counteract them. So these mythologies grew around the Euro, transfiguring it as an instrument for peace, a means to bring Europeans together, a necessity for the Single Market. All these strands of mythology grew up and around the European project to sustain what is, effectively, a mindless idea.

spiked: You talk about it almost as a triumph of political delusion. What drove its architects on? What allowed them to push forward with a project that many economists deemed a folly?

Mody: I learnt two things about history from doing the book. One, that there are critical moments in history when an individual becomes unusually powerful, and acquires an executive power disproportionate to his or her abilities. And two, such an individual has within his or her power an ability to create a narrative, a story, a mythology. And it is the combination of the two that created the Euro. This is why Helmut Kohl is so important, not only because he shepherded this project to the end, [but also because] he left us with a legacy of language that justifies it even to this day. I think if Kohl hadn’t existed, or hadn’t survived as chancellor in the 1990s, it wouldn’t have happened – there would have been no Euro.

spiked: What’s striking is that rarely during this decades-long process of integration did those leading the charge engage with national electorates. If they did engage, they would just ignore the answer given, as they did as far back as 1992, with the Danish and French referenda on the Maastricht Treaty. Do you think that this is one of the fatal flaws of European project – that it goes onwards, in spite of citizens?

Mody: It is absolutely a fatal flaw. Up until 1992 and the Maastricht Treaty, there was this concept of permissive consensus. This idea said that European leaders were to take benign decisions on behalf of the peoples of Europe, who cannot possibly understand the complexities of governing. They trust the leaders, because they know the right way to move forward. And ultimately they will be validated and legitimised by the fruits they will deliver.

Yet this permissive consensus was breaking down even as the Maastricht Treaty was being signed. As you say, we had the Danish referendum, and especially the French referendum in 1992. The French referendum, in particular, is an historically important one because the people (49 per cent) who voted against Maastricht are the same as those protesting in the yellow vest movement today. Just think about it. For a period of about 30 years, a consistent group of people have been calling out, saying there is a problem over here. They are saying that the real problems lie at home, that we are being left behind, and you, the government, seem to have no clue what we want.

The question of whether European citizens want more Europe has never been really deliberated in any meaningful way. It was never clear what the point of the Euro was. It certainly didn’t deliver more prosperity. And the lack of consultation with the people has created a simmering anxiety of opposing kinds in different nations. In Germany that anxiety plays on the possibility that Germans may have to pay the bills for other countries. In much of southern Europe, people are anxious that Germany has become too dominant, and that, in periods of crisis, the German chancellor may become de facto European chancellor.

There is no electoral mechanism for accountability and legitimacy. So the whole process is inherently undemocratic – the people who are affected by decisions cannot vote out those making the decisions.

spiked: There are some who claim the Eurozone has created a degree of prosperity, certainly from the late 1990s until the mid-2000s. Do you think this was an illusion of prosperity, sustained by, in Europe’s case, the banking bubble?

Mody: Yes, absolutely. It is very unfortunate because that whole decade was completely misinterpreted in two ways. One is that when the yields on government bonds came down, that was still celebrated as financial integration, whereas it was in fact a problem because the countries that were benefiting from these very low interest rates were allowing a debt bubble to form.

And, second, what also happened, especially from 2004 until 2007, was that world trade was booming. Firstly, because America was living beyond its means, and therefore importing a lot of goods from the rest of the world; and, secondly, because China was coming into the global trade market in a big way and, in becoming a major exporter, was also becoming a major importer. Therefore, the years 2004 until 2007 feature world-trade growth rates that are higher than any in recent memory. And when world trade grows, European trade grows rapidly.

So the combination of the convergence in interest rates, which gave the sense of financial integration, and the growth in world trade, which gave people the sense of prosperity, allowed some to conclude, yeah, this thing has worked. So, in June 2008, you have Jean-Claude Trichet, the then president of the European Central Bank, declaring the Eurozone a great success. This was the moment when the Eurozone crisis was actually hitting hard. It just wasn’t evident to the ECB.

George Orwell said of the reporting of the Spanish Civil War that history was being written as it is supposed to be rather than how it was. That is very much how the first decade or so of the Eurozone was reported.

spiked: The crisis starts to register in the Eurozone from 2009. Why were you so opposed to the the policy of austerity the Troika imposed on Greece and Ireland?

Mody: I understand that if a country has lived beyond its means it has to tighten its belt. I’m not contesting that. What people like me objected to, and continue to object to in the case of Italy, is the timing and the speed of fiscal consolidation. When an economy is going into a recession, fiscal austerity makes things worse. Government taxes increase as its spending decreases, and therefore the recession becomes deep. There is no mystery to this.

So my position is that, yes, Greece clearly needed some austerity, but it needed to go at a slower rate. If trauma patients come into surgery, you don’t tell them to run round the block a few times as a show of good faith before you treat them. It’s as basic as that. Austerity therefore made the Greek problem infinitely worse.

spiked: It’s striking that the EU seems so committed to strict fiscal and budgetary rules, certainly in the case of Greece. Why do you think that is?

Mody: I wish I could give you a simple answer. My historical answer is that the EU is not rule-bound. When the rules are not suitable to those who matter, those rules are violated, and for good reason. We saw that in 2002 and 2003 when Germany, in the midst of a recession, thumbed its nose at the fiscal rules to avoid making the recession worse. German finance minister Hans Eichel wrote an op-ed in the Financial Times justifying the decision, which Yanis Varoufakis should have had the good sense to recite when making his case for the relaxation of budgetary rules in relation to Greece.

The rules get trotted out only when the power balance goes in the opposite direction, and then they are used as an instrument to bring the so-called errant nations, be it Greece or Italy, in line.

spiked: You call Italy the ‘faultline’ in the European project. Why do you think it is so central?

Mody: There is no question that Italy is and remains the faultline of Europe for many reasons. First, it is large – its GDP is about eight or nine times the size of Greece; and its financial assets are of the same order of magnitude as Germany or France. Second, Italy has chronically low productivity growth – since it joined the Eurozone, productivity has fallen by something in the region of 10 to 15 per cent. Now, not all this is the Eurozone’s fault. Low productivity in Italy is, in large measure, an Italian problem, due to a severe lack of momentum within the Italian economy, and a series of governments unable to tackle the problem.

But a country that has low productivity growth needs the crutch of occasional exchange-rate depreciation. No one contests that. No one contests the fact that if you are not productive, you become less competitive, and, if you’re less competitive, you need to devalue your exchange rate. But Italy is in a trap. It cannot devalue its exchange rate against the Deutschmark because the two currencies are in parity within the Eurozone, and because the ECB monetary policy remains relatively tight, the Euro has not depreciated against the US dollar in the past 20 years. Therefore the Lire, such as it is embedded in the Euro, has not depreciated against the Deutschmark or against the US dollar over the course of 20 years, during which time productivity has continued to fall. So how can this country repay the large volume of debts it owes, without growing?

That is the core Italian problem. Italian productivity needs a generational investment in schools, in research, in bringing back people who have left, in order to build a new sense of self-confidence, which it utterly lacks right now.

spiked: When I’ve been to Italy recently I’m struck by the instances of anti-German grafitti. Do you think that one of the greatest ironies of this project of supposed economic and political integration is that it has actually fostered enmity among European nations, rather than unity?

Mody: As I said, Nicholas Kaldor predicted exactly that in 1971. He said that a single currency will amplify existing economic divergences, and, if it does that, it will deepen political divisions. He even quoted Abraham Lincoln: ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ Kaldor’s ghost is stalking the Eurozone.

spiked: Do you think that restoring a degree of national sovereignty to European nations would actually bring European people closer together again?

Mody: Yes, I do. I ask myself the question, what is it that brings Europeans together? What is the foundational reason for Europeans thinking of themselves as European? Nearly 70 years ago, Schuman called for a common foundation for economic development to create a federation. The idea of a federation has gone, as has the belief in a common foundation for economic development. Therefore, you have to go back to Schuman’s other proposition: that Europeans need to hold together in the interests of peace. In the modern sense, that can be extended to the protection and preservation of democracy, and the furtherance of human rights. Europeans need to ask themselves if they still believe in those values – the values of an open society – and are they willing to work towards the creation of an open society in which peace, democracy and human rights are fostered. If that is not the purpose of Europe today, then it is not clear to me what is the purpose of Europe.

Ashoka Mody is a visiting professor in international economic policy and lecturer in public and international affairs at Princeton University. He is the author of EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts, published by OUP. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

He was talking to Tim Black.

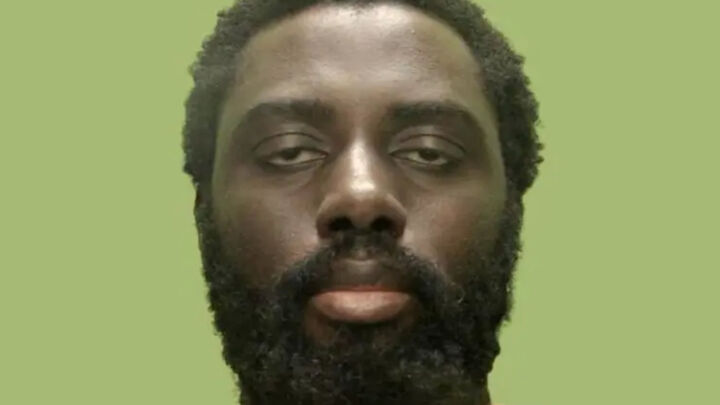

Picture by: Getty.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.