How Mervyn Peake was almost forgotten

His work could so easily have slipped from the public consciousness.

Shortly after the author Angus Wilson turned 70, he took the then 35-year-old Salman Rushdie to lunch at the Athenaeum Club in London. Rushdie was the new doyen of the literary scene, lately the recipient of the Booker Prize for his breakthrough novel Midnight’s Children. During the course of the meal, the tone turned wistful. ‘I used to be a fashionable writer’, said Wilson, who in 1958 had won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Middle Age of Mrs Eliot. Rushdie later wrote of the encounter in his memoir, summarising Wilson’s message as ‘the wind always changes; yesterday’s hot young kid is tomorrow’s melancholy, ignored senior citizen’.

Today is the 50th anniversary of the death of the novelist Mervyn Peake (1911-1968), and although he has a devoted following, the uniquely bizarre nature of his work has always kept him at the periphery of popular culture. Like Wilson, he fell out of favour with the general public, and for a while there was a risk that he might be forgotten. I once had a fascinating discussion on this subject with the late Sebastian Peake, Mervyn’s eldest son, who had worked tirelessly to ensure that his father’s legacy would be preserved. Sebastian clearly understood that quality and innovation are no guarantee of longevity when it comes to artistic trends. One need only consider the likes of Stella Benson or Forrest Reid to appreciate that even the most brilliant and acclaimed writers can fall into obscurity.

Peake is best known for his first three novels – Titus Groan (1946), Gormenghast (1950) and Titus Alone (1959) – which tell the story of Titus, the 77th earl of Gormenghast, an ancient decaying castle in an unknown world. The books were never intended to form a trilogy, but after Peake developed Parkinson’s disease, his powers quickly faded and further volumes became impossible. After his death, the prevailing wisdom was that writing such dark stories had sent him mad. But in reality Peake and his doctors were struggling with a condition they did not fully comprehend.

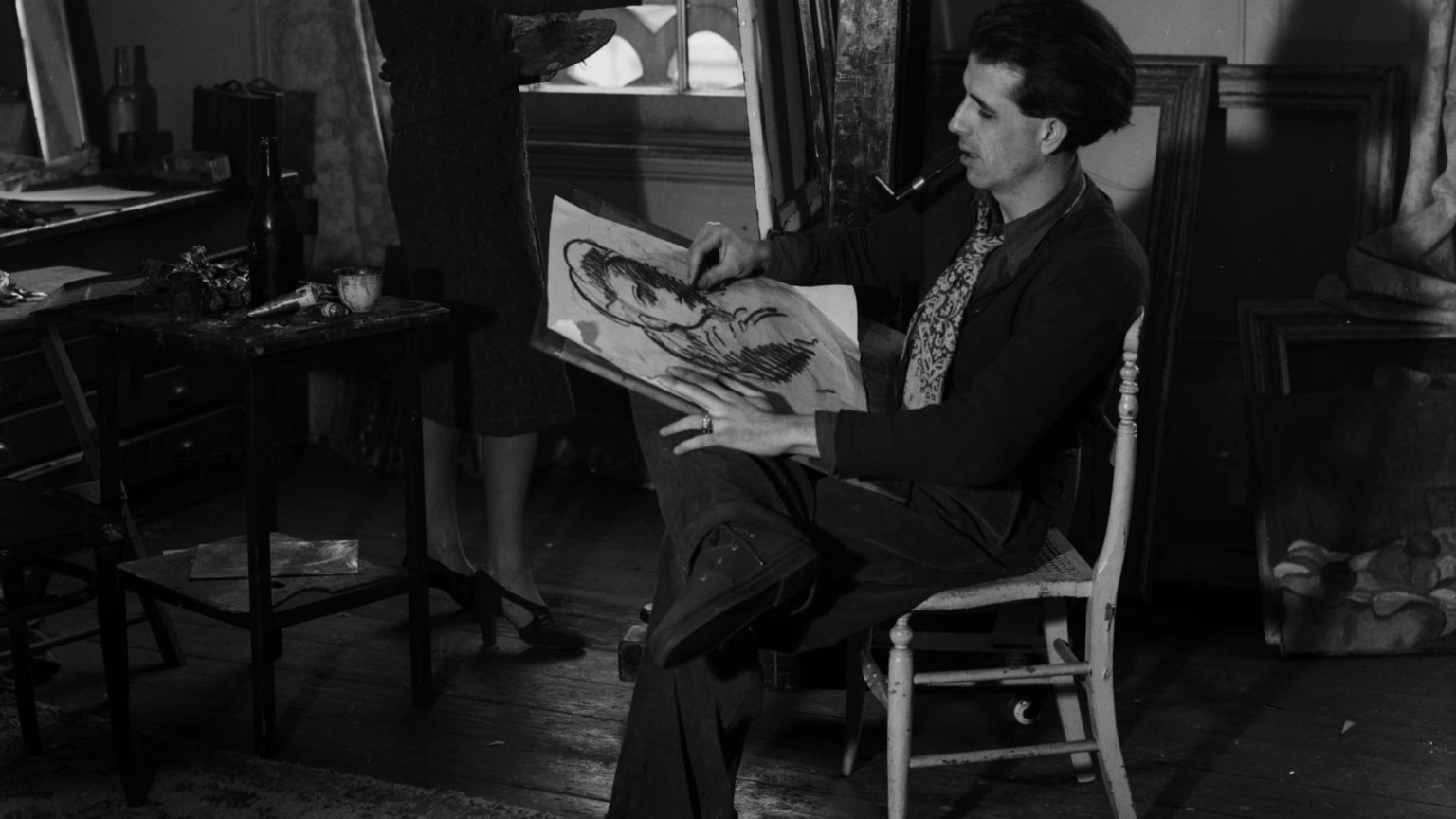

Peake was in vogue for a short while during his lifetime, but not really for his novels. As an illustrator he was, according to Quentin Crisp, ‘the most fashionable in England’. Peake is one of the few artists who have simultaneously excelled in prose, poetry and visual art. William Blake is the most obvious precedent, whose inimitable worldview was likewise reified through this combination of the verbal and the visual. Take, for instance, Peake’s illustration of a dying girl which he drew from life in his capacity as a war artist, and the poem he wrote about the experience, ‘The Consumptive. Belsen, 1945’.

The impact of this haunting picture is further heightened by the artist’s recognition, later expressed through verse, of his inability fully to capture her agony. It is a poem about the limitations of empathy; in spite of our need to find a human connection in the most devastating of circumstances, the artist is forced to acknowledge that we are ultimately alone.

Towards the end of Peake’s life, interest in his work was fading. The lukewarm reception for The Wit To Woo (1957), a play far too eccentric to be commercially viable, scuppered any hopes of a career as a dramatist. As his health further deteriorated through the 1960s, his books fell out of print, and there was a risk that he would be consigned to the growing list of undeservedly forgotten authors. Thankfully, his work was championed by Oliver Caldecott at Penguin, and the Gormenghast novels were reissued in the ‘Modern Classics’ series with illustrations from Peake’s notebooks. By this point, it was too late for Peake to enjoy the revival. The science-fiction writer Michael Moorcock visited him at The Priory to show him the artwork for the new editions. ‘He nodded blankly, mumbled something and lowered his eyes’, Moorcock recalled. ‘It was almost as if he could not himself bear the irony.’

Over the next few decades Peake’s reputation grew. He is now generally considered to be one of the most multi-talented and imaginative artists of the 20th century. In 2000, the BBC adapted Peake’s first two novels for television, but the interpretation failed to capture the darkness of his vision, favouring instead a kind of overwrought whimsy that veered into the outright cartoonish. It is to be hoped that the forthcoming television adaptation by Neil Gaiman will yield better results.

Peake’s work is often compared to JRR Tolkien, a comparison which makes little sense. Although the Gormenghast novels are generally classified as fantasy, the strange combination of brooding Gothicism and surreal comedy is almost a genre of its own. Unlike Tolkien, Peake’s characters are morally ambiguous. He has the Dickensian capability of infusing caricature with genuine humanity. Even Steerpike, the ruthless villain of the first two novels, has seen his conscience corroded by years of resentment and unfulfilled ambition. Peake allows us to follow his journey from a downtrodden kitchen lackey to the Master of Ritual, our sympathy dwindling as his sociopathic nature leads him to increasing acts of cruelty. ‘His face remained like a mask’, Peake writes, ‘but deep down in his stomach he grinned’.

Gormenghast itself is a satire of the rituals that govern our lives. Sepulchrave, the Earl of Groan and father to Titus, is forced to enact the decrees outlined in ancient tomes, ‘activities to be performed hour by hour during the day’, which specify ‘the garments to be worn for each occasion and the symbolic gestures to be used’. Any significance that such symbolic rituals might have once carried have long been forgotten, and in any case vary depending on the earl in question. If, for instance, Sepulchrave ‘had been three inches shorter’, an entirely different set of regulations would apply. His quotidian duties draw him into a spiralling melancholia, until he eventually goes mad and is eaten by owls.

This kind of attention to detail is reflected in Peake’s meticulous narrative style. Take, for instance, his description of the grotesquely corpulent chef Abiatha Swelter. In Peake’s mind, even a gesture as small as a smile can disclose an almost metaphysical significance. ‘[A]cross his face little billows of flesh ran swiftly here and there until, as though they had determined to adhere to the same impulse, they swept up into both oceans of soft cheek, leaving between them a vacuum, a gaping segment like a slice cut from a melon. It was horrible. It was as though nature had lost control. As though the smile, as a concept, as a manifestation of pleasure, had been a mistake, for here on the face of Swelter the idea had been abused.’ The moment is both baleful and absurd, a point only accentuated by the rhetorical excess.

For Anthony Burgess, author of A Clockwork Orange (1962) and Earthly Powers (1980), it is Peake’s boundless invention and his ‘aggressively three-dimensional’ prose that makes Titus Groan a masterpiece. ‘It remains essentially a work of the closed imagination’, Burgess writes, ‘in which a world parallel to our own is presented in almost paranoiac denseness of detail. But the madness is illusory, and control never falters. It is, if you like, a rich wine of fancy chilled by the intellect to just the right temperature. There is no really close relative to it in all our prose literature.’

It is far too easy to assume that the best artists are guaranteed a lasting place in the public’s affection. Without the persistence of the likes of Anthony Burgess, Oliver Caldecott and Michael Moorcock, Peake’s work might well have slipped into literary oblivion. The landscape of English literature is all the richer for their efforts.

Andrew Doyle is a stand-up comedian and spiked columnist. He is also the co-founder of Comedy Unleashed, London’s free-thinking comedy club. Follow Andrew on Twitter: @andrewdoyle_com

Watch Andrew Doyle in The Curious Case of the Nazi Pug below:

Picture by: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.