No more memes? The EU’s latest threat to the net

The EU’s new copyright laws will destroy the web as we know it.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It has been dubbed the end of the internet as we know it. Inventor of the world wide web Tim Berners-Lee, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales and 70 other tech figures have penned an open letter, warning of the ‘imminent threat’ to the internet’s future, which would turn it ‘from an open platform for sharing and innovation, into a tool for the automated surveillance and control of its users’.

This threat to the net comes from the EU’s new copyright directive, which was passed narrowly by its Legal Affairs Committee, with 13 votes in favour and 11 against in a secret ballot. (A great deal of EU law-making occurs in secret.) The law is intended to crack down on the streaming of pirated films and music. But the actual scope is so large that it covers all and any copyrightable material.

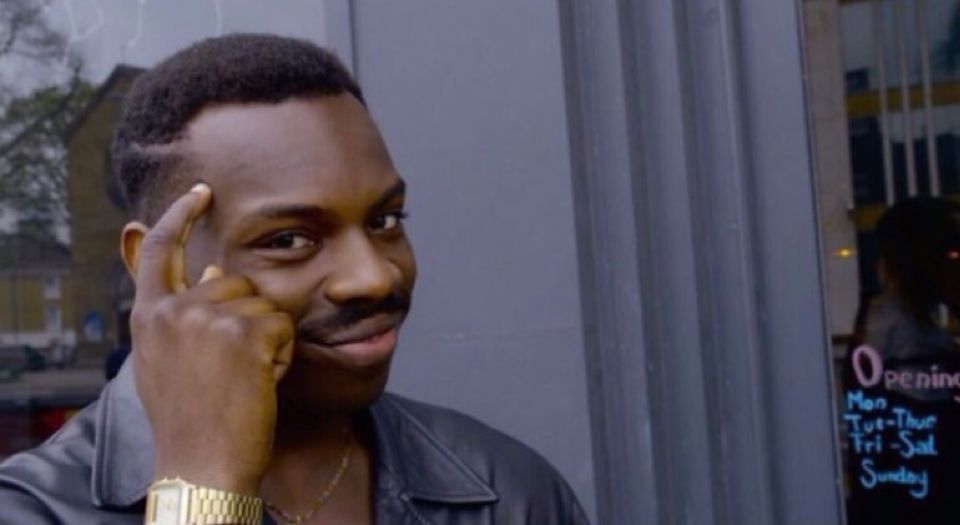

Of particular concern to campaigners is article 13 of the directive, which could outlaw the sharing of memes – a major aspect of today’s internet culture. The law shifts the burden of responsibility for copyright infringement from individual users to platforms. Platforms will be ordered to install ‘content recognition technologies’ to detect and delete copyrighted material. Jim Killock, executive director of the Open Rights Group, tells me that ‘anything that matches a copyright database’ would face deletion, ‘so memes and the reuse of popular culture would absolutely be in scope for removal’ – even if done legally.

Copyright laws are not inherently a threat to free expression. It is wrong fraudulently to take credit for other people’s work and it is important that artists and creators are paid for what they produce, unless they intend to share it for free. But we cannot reasonably expect copyright law to be enforced by algorithm. When copyright cases end up in court, the process is complex and lengthy. Recognition tools, on the other hand, would make judgements in split seconds. Arguments over the value of building on the work of others to create something new and original – the essence not only of meme culture, but of all artistic endeavour in human history – will be lost on the EU’s censorship machines. The European Commission has responded to complaints about the policy by saying that users will be able to appeal against deletion under a ‘parody exemption’. But this actually confirms campaigners’ worst fears – that platforms are expected to delete first, ask questions later.

What’s more, we clearly cannot rely on social-media companies to stand up for their users. Now that the platforms will be liable for their users’ posts, the rules will be enforced zealously. In Germany, for example, the NetzDG law against posting ‘unlawful’ content on social media has led to the censorship of artists, of satirists and even of the government minister who drew up the law. Facebook and Twitter have been desperate to avoid hefty fines and so err on the side of censorship.

Equally concerning in the EU’s copyright bill is article 11, which makes provisions for a so-called ‘link tax’. While some news publishers have lobbied hard for these changes, as they believe it will force Google and Facebook to fork out for hosting their material, Killock tells me they are ‘shooting themselves in the foot’. It could see previews of pages removed and search results suppressed, reducing traffic to news sites, he says. It would damage smaller, innovative websites while boosting the tech giants, ‘who may find ways to make arrangements with the news industry, whether that is paid for or free.’

All of this comes on top of existing laws like GDPR, which, a month after implementation, is blocking European users from accessing some US-based websites. The cost of complying with a fearsome 57,509 words of EU legalise is not worth it for many sites. Major news outlets like the LA Times, the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News are now inaccessible throughout the EU. Popular smartphone apps like Instapaper and Unroll.me are similarly blocked in Europe.

Since the EU referendum, Remainers have peddled a fantasy of an open, free and liberal EU. That fantasy is colliding with reality on a daily basis. The EU’s protectionist trade arrangements are a barrier to open trade and now its new copyright policies threaten the open internet and, by extension, the open society. Thanks in part to the illiberal EU, Europe’s status as a beacon of liberty is dimming considerably. Brexit cannot come soon enough.

Fraser Myers is a writer. Follow him on Twitter: @FraserMyers

Picture by: YouTube

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.