The ugliness of the ‘dead white male’ debate

Saying that black kids can’t relate to Shakespeare is deeply reactionary.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Pity the ex-students of Mary Bousted, former English teacher and currently joint head of the National Education Union. If you’d sat through her lessons when she taught in Harrow in the 1980s, you might have asked yourself why you were studying an obscure Chinese novel and not Hamlet or Julius Caesar like the kids do at the posh schools.

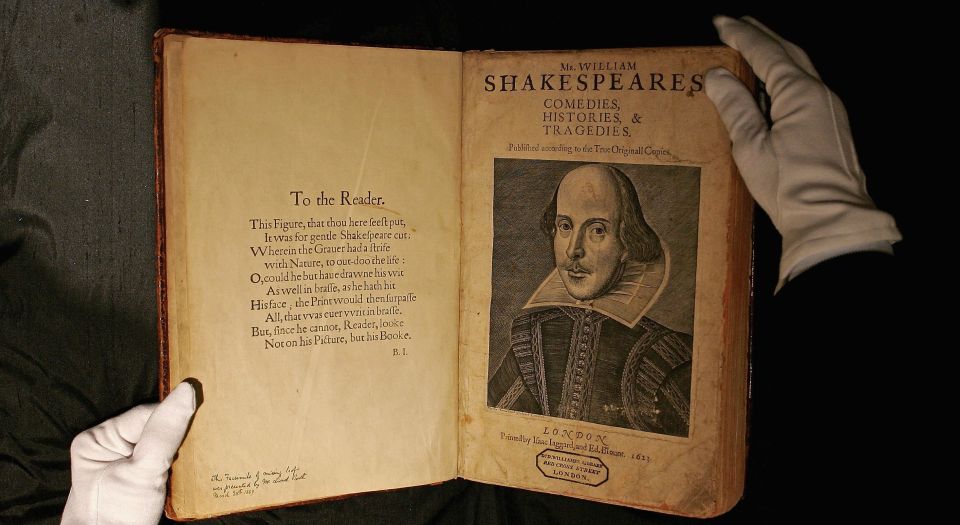

If what she told delegates at the Bryanston Educational Summit last week is anything to go by, she might have told you that, while she didn’t have a problem with Shakespeare, his work was ‘intensely conservative’ because he ‘wrote a lot of the time to bolster the divine right of kings’. This is why, while others might consider Shakespeare to be the greatest writer in the English language, she isn’t very keen on schools teaching him. And according to Bousted, Chinese, Indian or Afro-Caribbean pupils aren’t interested in him either – because Shakespeare is white and dead.

Upon reading ‘if you prick us do we not bleed?’ or ‘this above all: to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not be false to any man’, what kind of person – let alone teacher – thinks, ‘but you’re only saying that because you’re white’? The answer is: a philistine.

The term philistine’s current usage was coined by Matthew Arnold in his landmark 1869 book Culture and Anarchy. In it, he argues that the point of education is to pass on the best that has been thought and said to succeeding generations. It was precisely this attitude that Bousted was targeting in her Bryanston speech. ‘If a powerful knowledge curriculum means recreating the best that has been thought by dead white men – then I’m not very interested in it’, she said.

Although the complaints about dead white males appear distinctly modern, Bousted is actually restaging a battle fought over 150 years ago – between knowledge and skills. When Arnold writes of the ‘philistines’ in the 1860s, he has in mind the new class of industrialists who thought the ‘sweetness and light’ of classical learning was outdated and was holding England back from competing on the world stage. They wanted new, mechanistic approaches to education, which would help to grow the economy. When Bousted calls for a skills-based approach to education, as practised in countries like China, and decries England’s curriculum as ‘not fit for the world in 2018’, she echoes the Victorian philistines.

In her speech, she tried to present herself as not being against knowledge per se. She employed the edu-speak equivalent of ‘I’m not racist, some of my best friends are black’, name-dropping Pope, Dryden and Shelley as authors she has ‘no problem’ with. She said that it is important for students to know ‘some of the best that has been thought and said’, but that they should also know that putting Shakespeare on the curriculum ‘was a choice that was made and a choice made by the powerful’.

In this, she doesn’t seem to understand what the contemporary debate over the role of knowledge in the curriculum is all about. In raising the question of the ‘powerful’ when it comes to knowledge, Bousted is alluding to the work of sociologist Michael Young. In his 2007 book, Bringing Knowledge Back In, Young establishes two opposing types of knowledge: ‘powerful knowledge’ and ‘knowledge of the powerful’. For Young, the ‘knowledge of the powerful’ is exclusively owned by the elites and is the knowledge that helps to sustain their position in society. ‘Powerful knowledge’, on the other hand, is learning that can liberate students from their social, intellectual and economic constraints. It is the sink-estate kid’s knowledge of Shakespeare, he argues, that will one day enable him to beat an Etonian to a place at Oxford. Bousted ignores this distinction. Powerful knowledge is key to the kind of social mobility that Bousted is calling for. But she confuses it with white privilege and attacks it instead.

Knowledge itself cannot be tainted by power. Literature and mathematics were once the possession of the most elitist, insular and privileged castes that have ever existed in human history. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t teach these subjects. The baby and the bathwater are different things. The works of Shakespeare, Milton and Chaucer are sublime and universal. To judge their value on the basis of the colour of the skin of their author – or of the reader – is deeply reactionary.

Bousted’s speech might have excited a number of the new philistines for its attack on a knowledge-based curriculum and its seemingly progressive call for greater diversity. But for me at least, it was ‘a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’.

Gareth Sturdy is a science teacher in south London and an organiser of the Academy of Ideas Education Forum. Follow him on Twitter: @stickyphysics

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.