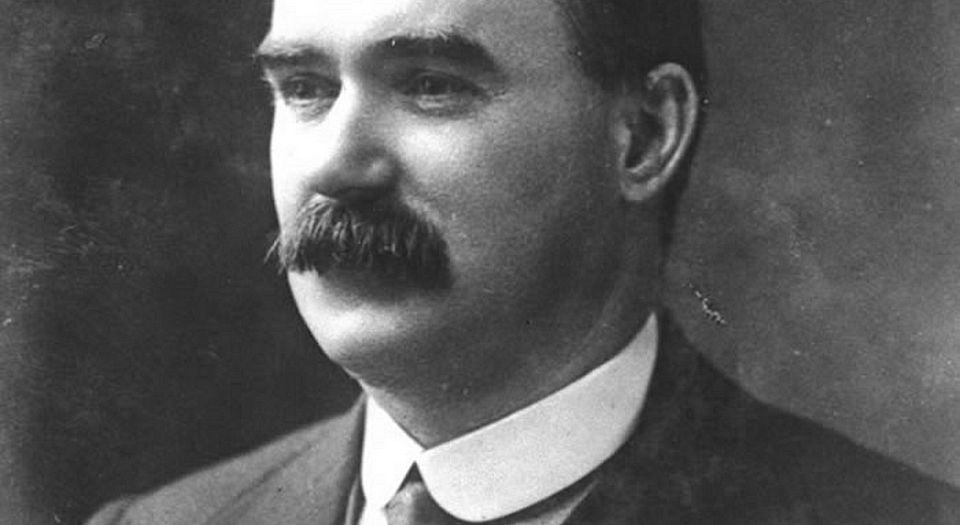

James Connolly: a full life

In praise of the hero of Easter 1916, on his 150th birthday.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘ Hasn’t it been a full life, Lillie, and isn’t this a good end?’ – James Connolly speaking to his wife on the eve of his execution.

Edinburgh’s Cowgate has changed much in the past 150 years. Once known with little affection as ‘Little Ireland’, it was populated primarily in the 1850s and subsequent decades by Irish migrants in single-room dwellings. Though the Irish community constituted a considerably smaller percentage of the population of Edinburgh than other British cities like Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow, it seemed they all lived on top of one another in the Cowgate. The area would produce Hibernian FC, founded by the congregants of St Patrick’s Church. With the exception of the church itself and a humble plaque to James Connolly, there is little trace of its migrant history today.

James Connolly, born 150 years ago this week, was perhaps unique among the leading socialist thinkers of his day, in that he did not merely write about the working class, but came from within it. The son of a Monaghan-born immigrant who shovelled animal excrement off the streets of the Scottish capital, poverty was not an abstract concept to Connolly, but something which shaped his political thinking and philosophy.

Even in comparison with the Cowgate, the poverty of the Dublin that Connolly inhabited from the time he was lured to the city by the fledging Dublin Socialist Society in 1896 was truly shocking. One 1918 Housing Report to the Dublin Corporation pondered if ‘the rebellion of 1916, with its results in loss of life… might possibly have been prevented if the people in Dublin had been better housed’. A woefully inadequate Corporation had played no small role in the rot of tenement Dublin, with one inquiry revealing that 16 members of the Corporation were themselves slum landlords. That some of these men were self-professed nationalists was an irony that was not lost on Connolly.

Of all the leaders of that 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, Connolly is the one who has undoubtedly held the most enduring appeal. Others have been denigrated with time, none more so than Patrick Henry Pearse, dismissed as a fanatic seeking ‘blood sacrifice’, though his language was very much of its time. It was not Pearse but constitutional nationalist leader John Redmond who championed Irish soldiers in the ranks of the British army on the battlefields of Europe, ‘offering up their supreme sacrifice of life with a smile on their lips because it was given for Ireland’.

Connolly’s continued relevance stems from what he wrote of, grappling with economic and social questions and maintaining that ‘Ireland, as distinct from her people, is nothing to me’. It was not the changing of flags that interested Connolly, but the overthrow of the existing social order.

Did Ireland offer a particularly unfruitful terrain for socialism? The dominance of Home Rule nationalism, which sought to unify social classes behind the idea of Irish national self-governance within the British Empire, was one obvious hindrance. But so too were sectarian tensions in the north-east of Ireland and the intense poverty of rural Ireland. Friedrich Engels took a dim view of Irish prospects, writing in September 1888 that ‘a purely socialist movement cannot be expected in Ireland for a considerable time. People there want first of all to become peasants owning a plot of land.’ With the exception of Belfast, where both the linen industry and shipbuilding employed very significant numbers of working-class people, much of Ireland was defined by its absence of industry. The 1901 and 1911 census returns make this perfectly clear in the Irish capital, where ‘General Labourers’ were in abundance within the Dublin workforce, doing whatever work was available when it was available.

In spite of these challenges, Connolly formulated a type of socialist thinking that was unique to the difficulties Ireland presented, and was rooted in the Irish historical experience. In Labour in Irish History, a groundbreaking Marxist survey history of Ireland published in 1910, Connolly proclaimed that ‘the Irish question is a social question, the whole age-long fight of the Irish people against their oppressors resolves itself, in the last analysis into a fight for the mastery of the means of life, the sources of production, in Ireland’. (The study is not without its faults, however, not least in its sometimes bewildering presentation of Gaelic Ireland as a sort of proto-socialist society.)

Greatly influenced by the radical trade unionism of the Industrial Workers of the World (the ‘Wobblies’) in the United States, where he spent several years as a union organiser and socialist activist, Connolly was central to the formative years of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, a union with strong syndicalist influence created by Jim Larkin in Dublin. Its headquarters, Liberty Hall, was denounced by the Irish Times as ‘the centre of social anarchy in Ireland, the brain of every riot and disturbance’, while the Manchester Guardian was moved to proclaim that ‘no Labour headquarters in Europe has contributed so valuably to the brightening of the lives of the hard-driven workers around it… it is a hive of social life’.

The vision of Larkin and Connolly was shaken to its very foundations in the Dublin Lockout of 1913, when a well-organised confederation of Dublin employers utilised their own form of combination (the thing they feared most from the union), collectively to lock out more than 20,000 Dublin workers who were members of the union. The effect was catastrophic, with the union greatly weakened in defeat and a broken Larkin departing for the US, leaving Liberty Hall in the hands of Connolly by 1914.

And yet, how quickly the Lockout was forgotten, as the drums of war on the continent were so clearly heard in Dublin that 25,000 young Dubliners marched to the trenches of Europe, including this writer’s young great-grandfather. Across the continent, the socialist Second International failed entirely in its promise to oppose the war between empires. At their 1912 conference in Basel, the Second International had boldly proclaimed that, ‘In case war should break out anyway it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination’. When the conflict came, however, many socialist parties rallied behind their respective national war efforts, to be denounced by Rosa Luxemburg as ‘the shield-bearers of imperialism in the present war’. It remains one of the greatest failures of the socialist left in its history.

Luxemburg, Connolly and others felt the great betrayal of the Second International keenly. Immediately, Connolly began calling for insurrection. In a furious speech in August 1914, he informed the gathered crowd that ‘you have been told you are not strong, that you have no rifles. Revolutions do not start with rifles; start first and get your rifles after. Our curse is our belief in our weakness. We are not weak, we are strong. Make up your mind to strike before your opportunity goes.’ It was uncharacteristically reckless language from Connolly, but indicative of great frustration.

Whether Connolly was correct to align with the nationalist Irish Volunteers in bringing about insurrection has been the subject of much debate. It was a former comrade, Seán O’Casey, who was among the first to criticse the alignment of the two, maintaining that ‘Labour had laid its precious gift of Independence on the altar of Irish nationalism’. Yet undoubtedly the vision of Connolly had remained social as well as national; only weeks before the insurrection, he wrote in The Workers’ Republic that ‘Ireland seeks freedom. Labour seeks that an Ireland free should be the sole mistress of her own destiny, supreme owner of all material things within and upon her soil.’

For the international socialist left, the Rising presented a conundrum of sorts. Yet Connolly made no apologies to socialists who questioned the wisdom of bringing his Irish Citizen Army into the fight, telling his daughter Nora: ‘They will never understand why I am here. They forget I am an Irishman.’ While condemned by some socialists on the continent as a mere ‘putsch’ of little importance, perhaps the finest defence of the Rising came from within the pages of The Woman’s Dreadnought, the newspaper of Sylvia Pankhurst. It noted that, ‘Poets and dreamers do not make revolution. There must be popular unrest behind even the smallest revolt. In Dublin it is impossible for men and women of the working class to live like human beings.’

There is little point in pondering what Connolly, Pearse or their generation would think of contemporary Ireland, though plenty across the political spectrum have been willing to speak for them in the decades since Ireland’s contested revolution, even utilising their images and words in the recent abortion referendum. What remains inspiring about James Connolly is that someone from such humble working-class beginnings could make such a significant impact on the course of Irish history and consciousness. From the Cowgate to the General Post Office, it was a full life.

Donal Fallon is is a historian, author and broadcaster based in Dublin. His most recent publication is Revolutionary Dublin: A Walking Guide (Collins Press, 2018, with John Gibney). Buy this book from Amazon (UK).

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.