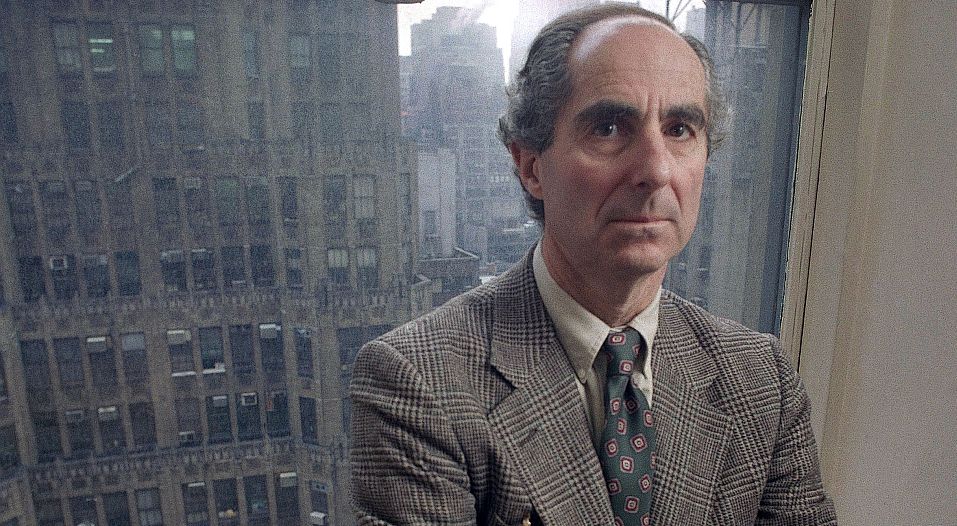

The Great American Novelist

Philip Roth’s American Pastoral is one of the finest novels of all time.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Philip Roth, the celebrated American novelist, died last week. On re-reading his American Pastoral recently, I was struck by how much more important it feels today than when it was first published 21 years ago. It is a, if not the, great American novel.

It is a profound examination of the human condition, and it is also, crucially in the modern context, a critique of the Sixties and of the rise of the Me generation. Roth should have won the Nobel Prize for Literature for this and the two other novels in his great trilogy about America: the Human Stain and I Married a Communist. He is head and shoulders above virtually all the winners of the past 30 years.

Set mainly in the late 1960s, American Pastoral charts the rise, decline and fall of Seymour Levov, a Jewish boy known as the Swede because of his blond hair, who aspires to live the American Dream. A football player, ex-marine and successful businessman, he is idolised by his peers. He marries a gentile beauty queen. The Swede is a man who, like the immigrant in The Godfather, ‘believes in America’. His ‘American Pastoral’ means raising his family in an idyllic country retreat. He gives up his Jewishness in order to assimilate into the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant ascendancy.

The Swede’s tragic decline stems from his troubled relationship with his daughter, Merry. Roth turns this family dysfunction into a study of the decline of America as a global power; the hollowness of the American Dream; the hypocrisies of the bourgeois family; the coming undone of the American immigrant melting pot; the decline of the US as a manufacturing nation; and the rise of narcissism.

The genius of the novel is that it brings all of these themes into focus through dissecting the central relationship between the Swede and Merry. And while it would be hard to call the book funny, it is full of ironic twists and turns. The last hundred pages are a dinner party from hell.

Roth tells us at the beginning that this is the story of a modern Job, and so it is. As tribulations and humiliations are heaped on the Swede, there is no redemption, only a stripping away of illusions. However, it is not God punishing him; rather, he is a victim of his own illusory belief in America as the Shining City on the Hill. His relentless decline and agonising fall are the result of profound changes in American society which he is both complicit in and also the victim of. The Swede’s own conclusion is bleak:

‘He had thought most of it was order and only a little of it was disorder. He’d had it backwards. He had made his fantasy and Merry had unmade it for him.’

Roth looks at the Sixties not as the period of liberation for women and gay people or of Third World liberation, ideas that formed Baby Boomers like me, but rather from the other side. He looks at it not as a decade of freedom, but as a time in which we witnessed the death of decency and of the American way, and the birth of a new narcissism.

He shows how the pre-Sixties parents, the Swede included, lost faith in their own beliefs and unwittingly encouraged the Sixties generation to rebel. The Swede’s pastoral idyll is exploded by the Vietnam War, the moment when the US lost its way, which fuels Merry’s rage against the whole of traditional America, and her own family. Merry sets off a lethal bomb and disappears into the underground subculture of the Weatherman. The Swede’s tribulations reflect the agony of American parents in the Sixties, when they discovered, in Dylan’s words, that their sons and their daughters were beyond their command.

This novel is both timeless and timely, Old Testament in scope yet also showing how we got from the Me generation to the You Must Not Offend Me generation. At the end, despite everything, Roth insists that the Swede was right to pursue the American Dream, of freedom, aspiration and integration. We can all agree with this, surely, because, in the words of the song: ‘You gotta have a dream, if you don’t have a dream, how you gonna have a dream come true?’

Rob Killick is CEO of Clerkswell. Read Rob’s blog, ‘UK After the Recession’.

Picture by: Joe Tabbacca/AP/Press Association Images

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.