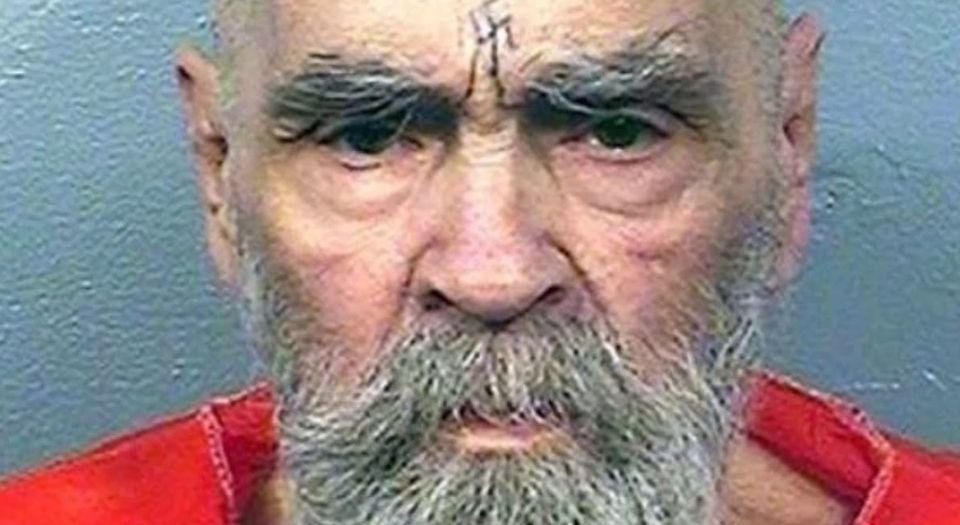

The meaninglessness of Charles Manson

Forget this fame-hungry psychopath. Remember his victims.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Charles Manson, who died this week aged 83, was a manipulative psychopath obsessed with achieving fame. In a different time, his malevolent and destructive energy might have found an outlet on reality television. But back in the late Sixties, he sought and gained notoriety by exploiting the mystique that surrounded the darkest sides of American culture.

The thoughtless, sadistic and entirely random nature of the murder spree that he inspired in 1969 caught America unaware. It was not simply the brutality of the murders committed by members of his cult – the Manson Family – that horrified the public, but also the casual and matter-of-fact way these killers revelled in their heinous acts. During their trial, Manson and his followers showed no regret for their crimes. On the contrary, Manson rejoiced in his growing reputation as the personification of evil. Unwittingly aided by the media’s fascination with his persona, he turned the trial into a performance of evil.

Manson often couched his performance in mystical babble, which attracted the attention of otherwise disoriented individuals looking for meaning in the incomprehensible violence perpetrated by his followers. A perverse attraction to the darkness of Manson’s behaviour meant that t-shirts bearing his face proved popular. For too many, he was more than just nasty, brutal scum. Rather, as Rolling Stone magazine depicted him on its front cover, he was a quasi-religious visionary, an unfathomable anti-hero. At times, underground newspapers treated Manson as if his incoherent narcissistic quest for fame actually meant something. The cumulative effect of this pop-culture fascination was that Manson became disneyfied.

Predictably, he also came to be caught up in the unfolding Culture Wars. Many critics of the Sixties counterculture seized upon Manson’s crimes as the inevitable outcome of the drug-fuelled hippy way of life. He became a major figure in the teleology of evil that opponents of Sixties radicalism constructed in order to argue that the counterculture was inherently immoral and destructive. A front cover of Life magazine declared the Manson cult ‘The dark edge of hippy life’. From this perspective, the flower-power children of the Sixties were potential serial killers, threatening American safety. The figure of the brainwashed cult member even became something of an archetype, featuring in countless dramas about cults and serial killers.

It was during the Sixties that the current Culture Wars over moral values began to influence public debate. For many traditionalists, the ‘anything goes’ rhetoric of the Sixties represented a fundamental threat to their way of life. In their eyes, Manson was not simply an evil individual – he was also the personification of a lifestyle that threatened the social fabric. The brutal violence inflicted on Manson’s victims served as a warning against the edgy, experimental practices associated with the alternative lifestyles of the Sixties. Many media outlets framed the fate of the Manson Family as a cautionary tale about a social and cultural experiment that had derailed America.

Despite their differences, however, the conflicting interpretations offered by popular culture and by anti-Sixties commentators were united on one point: the Manson Family’s crimes conveyed some important meaning. Hence both sides attempted to draw some important insights and lessons from the random and arbitrary violence of this unhinged group of attention-seeking killers. As a result, they gave Manson what he always wanted: recognition and fame.

Since the Sixties, every mass murder in the US is followed by a vain attempt to endow such horrific experiences with meaning. The question of ‘what lessons can be learned’ follows every major school shooting or killing rampage. Inadvertently, it was precisely this fixation with finding meaning in meaningless cruelty that created Manson’s reputation as something more than a pathetic psychopath. Manson effectively profited from this attempt to invest his cruel disregard for human life with meaning. Yet there is very little to be learned from his destructive and inhuman behaviour. Evil has a habit of striking humanity in a random and unexpected manner.

Today, acts of random brutal violence are attention-seeking exercises. That is why we should do our utmost to ignore them or at least downplay their significance. So let’s forget about Manson, the violent, obsessive wannabe celebrity, and instead remember his victims.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. His latest book, Populism And The Culture Wars In Europe: The Conflict Of Values Between Hungary and the EU, is published by Routledge. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: Youtube

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.