It isn’t only the Chinese who chill academic debate

British academics criticising foreign censorship should look in the mirror.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

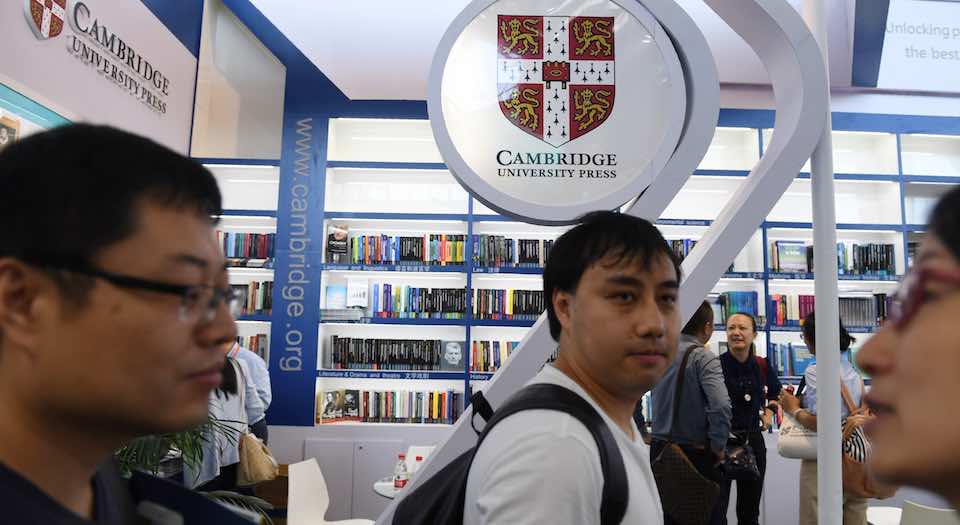

It seems academic freedom has not gone out of fashion after all. Following an international outcry from scholars and journalists, Cambridge University Press has this week reinstated over 300 articles it removed from its prestigious China Quarterly journal at the behest of the Chinese authorities.

Beijing officials had demanded not only that online access to politically sensitive articles be blocked in China, but that Cambridge University Press, the publisher, should take responsibility for the redaction. Articles considered offensive to the sensibilities of the Chinese government, on topics such as the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Cultural Revolution and President Xi Jinping, were to be taken down and Cambridge University Press, at first, cowardly acquiesced.

The response to this overt censorship, a very clear infringement of academic freedom by an oppressive and authoritarian regime was, rightly, loud and condemnatory. Over 1,000 academics from around the world signed a petition urging Cambridge University Press ‘to refuse the censorship request not just for the China Quarterly but on any other topics, journals or publications that have been requested by the Chinese government’. They denounced China’s bid to ‘export its censorship on topics that do not fit its preferred narrative’. The petition went on to threaten a boycott of the publishing company if the censorship continued.

Signatories added statements declaring their support for academic freedom and their opposition to state censorship and Chinese authoritarianism. BBC World Affairs Editor John Simpson Tweeted his support for the campaign: ‘I witnessed the Tiananmen massacre. China denies it happened. Now Cambridge Uni Press seems willing to go along with the Chinese approach.’

In response, Cambridge University Press announced on Monday that it would re-post all the redacted articles with immediate effect. Chastened, the publishing company agreed to reinstate the blocked content and ‘uphold the principle of academic freedom on which the university’s work is founded’. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Beijing has removed all mention of this climbdown from the Chinese internet.

It is shocking that a government should seek to control access to research and scholarship. No state should have the power to erase facts, rewrite the past and dictate only one approved account of events. That academic publishing companies from outside China appear prepared to accept such terms is truly appalling. The outcry that greeted Cambridge University Press is to be welcomed.

But unfortunately, threats to academic freedom today only rarely come from heavy-handed state bureaucrats or carry the reassuring stamp of being ‘foreign’. Opposing obvious state censorship – particularly when it comes from an authoritarian regime like China – allows campaigners and academics to take the moral high ground and act as valiant warriors for free speech. Yet these same people often fail to recognise the restrictions on free speech that occur closer to home.

Feted pseudo-radical Paul Mason argued in the pages of the Guardian that ‘there is no place in academia for craven submission to Chinese censorship demands’. Indeed. But this week it was announced that the British state, in the form of the police and the Crown Prosecution Service, will classify abusive and offensive messages on social media as a hate crime, with perpetrators now facing prosecution and harsher sentencing. I’ve searched high and low but I can’t find any statement from Mason criticising this expansion of state powers to restrict free speech. Criticism from academia collectively has also been deafening in its silence.

When the Chinese government bans articles it finds offensive, British academics and journalists are up in arms; but when the British government outlaws social-media comments people find offensive, the very same campaigners cheer the legislation on.

The campaign against Cambridge University Press also misses the more subtle way that academic freedom in the UK is restricted. Despite the 1,000+ petitioners arguing that, ‘as academics, we believe in the free and open exchange of ideas and information on all topics, not just those we agree with,’ many threats to free speech on campus today emerge from within universities themselves.

Earlier this month, Dr Judith Hawley, an academic from Royal Holloway, University of London, became the centre of a national news story for apparently ‘banning’ the first erotic novel in the English language, Fanny Hill, from her course on The Age of Oppositions. Hawley claims she has been misrepresented and she hasn’t banned the novel. But her suggestion that if she taught Fanny Hill her students would ‘slap me with a trigger warning’ is revealing about the way that academic freedom is curtailed today.

Hawley noted, in a radio documentary exploring free speech, that ‘in the 1980s I both protested against the opening of a sex shop in Cambridge and taught Fanny Hill. Nowadays I would be worried about causing offence to my students.’ Reasonably enough, commentators drew the conclusion that the novel had been dropped to protect sensitive students. Hawley, on the other hand, argued the book hadn’t been dropped because it was never on the syllabus.

She goes on to explain: ‘When I first taught this text in the 1980s, it seemed important to make sure that the issues raised by Fanny Hill, including desire, pornography and power, were discussed in an academic environment. That academic environment has changed: the student body is larger, more diverse, less privileged and more uncertain about the future, and the ubiquity of pornography has changed the terms of the debate.’

No university course can possibly cover everything that has ever been written and academics have to make decisions about what to teach. Leaving a book off a reading list is not censorship – it’s academic judgement. But academic judgement is now often exercised not with literary or intellectual merit in mind, but with a view to the assumed sensibilities of a larger, more diverse, less privileged student body. Despite criticism of ‘generation snowflake’, no students had been offended by Fanny Hill – they hadn’t been given the opportunity. Hawley might not have government officials dictating what should and should not be taught – but her assumptions about the vulnerability of students and her own desire to avoid being ‘slapped with a trigger warning’ meant she self-censored and decided to stop teaching the novel.

Threats to academic freedom need to be challenged wherever they appear and whatever form they take. There is indeed no place in academia for Chinese censorship, but at the same time we must not fool ourselves into thinking that Britain and America are bastions of academic freedom. It is great to kick off the new academic year with a positive assertion of the importance of academic freedom – but if it is to be more than moral posturing, then scholars and journalists alike need to be just as vocal in criticising threats to free speech that emanate closer to home.

Joanna Williams is the author of Women vs Feminism: Why We All Need Liberating from the Gender Wars.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.