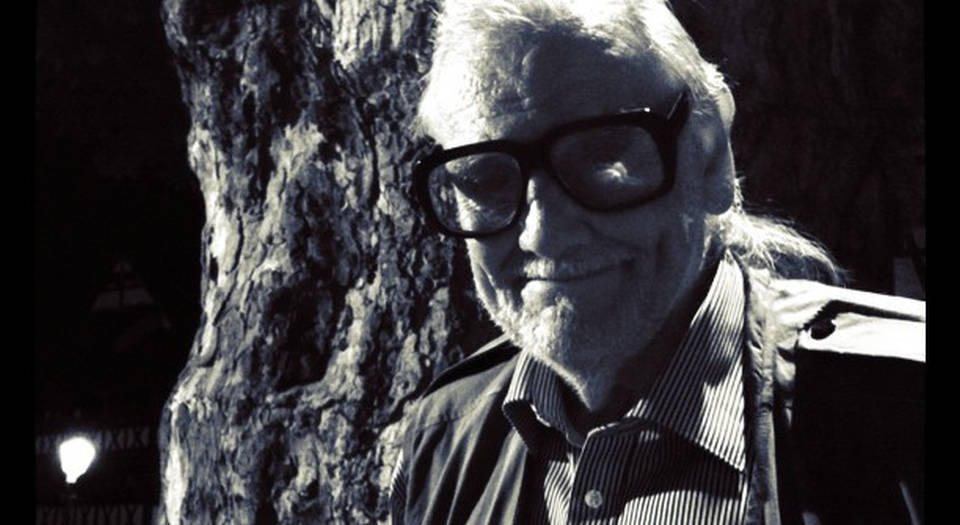

The undying legacy of George Romero

Few gave the idea of the zombie as much life as he did.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Film director George A Romero’s death this week, aged 77, marked the end of his ‘brief but aggressive battle with lung cancer’, as his producing partner, Peter Grunwald, said in a statement. It also marked the end of a directing career dominated by the undead.

Not that Romero, as he himself later admitted, ever intended to fill his work with zombies, or restrict himself to the horror genre. As this Bronx-born, University of Pittsburgh-educated child of the 1960s admitted in a 2008 interview: ‘You don’t grow up wanting to be a horror filmmaker, you grow up wanting to be a filmmaker. I wish that I had a wider range. I tried early on to do several films that were non-genre and nine people saw them, so I don’t have the credentials in that regard.’ Even Night of the Living Dead, the stark, monochrome, newsreel-effect film that catapulted Romero into the public consciousness in 1968, was inspired less by the zombie pulp fictions and films of the era, than by I Am Legend, a 1954 sci-fi horror novel by Richard Matheson, and its film adaptation released a decade later, The Last Man on Earth.

But, whether he wanted them to or not, zombies were forever to lumber into the foreground of Romero’s imaginative universe. And it is to all our benefit that they did. For Romero took this horrifying figure, which had began life as an undead wanderer as part of African slaves’ belief systems, before fearful colonialist writers added the spectre of cannibalism during the 19th century and turned it into the racially sublimated threat on Western societies’ margins, and revitalised it. The zombie became something other than a figure of colonial angst. It still ate flesh, and, in Romero at least, had the slow, exhausted gait of the San Domingo slave; but it expressed, served and addressed new anxieties, new fears.

This is clear right from the unsettling opening of Night of the Living Dead, in which brother and sister Johnny and Barbara pass a frayed US flag on their way to lay a wreath at their father’s grave. There is a sense that society is unravelling, that America is in decline, that something is rotting at society’s heart. Romero admitted last year that he felt at the time that ‘everything is falling apart’: ‘Back then, in 1968, everything was suspect – family, government…’ Despite Romero’s hippyish demeanour, there is nothing of the countercultural optimism that might have marked a film from earlier in that decade. Yes, Barbara and Johnny are young, and their faces are pressed determinedly against the window of the future – in a telling exchange at the beginning of the film, Johnny says he can’t even remember what their father looked like, and that the wreath-laying is an empty gesture. But in Night of the Living Dead, the past, America’s past, is not to be left behind. Too many wrongs have been committed, too much sin indulged. And now the past is literally rising up to claim and consume the tainted present.

This is a signal moment in the development of the zombie trope: it now becomes an amassed, society-wide figure of the apocalypse, the zombie as the grave-digger of a decaying, post-imperial West. In earlier zombie fictions, indeed Gothic fictions, dramatic tension is generated by the conflict between civilisation and barbarism – think of Van Helsing’s moth-eaten but still just-about-extant Christian faith in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But from Romero onwards, the tension between good and evil lessens, the line blurs. While the humans holed up in the Last Redoubt in Night of the Living Dead are bickering, petty and often unpleasant, the zombies are not so much evil as animal. You can hardly blame them for eating flesh – their nature compels them to. It’s the humans who are capable of behaving morally, and, in Romero’s vision, they often don’t. Civilisation is not counterposed to barbarism: it is treated as its document.

Romero’s achievement is to have transformed this nihilistic mood into a source of genuine horror. But then there was much from which he could draw sustenance. This, after all, was the moment of the Vietnam War, the moment when the prospect of an atomic End Times seemed imminent; the moment when the student counterculture of 1960s consummated itself in the terroristic Weathermen; the moment when the civil-rights movement ran up against lethal resistance – Martin Luther King was assassinated the same year Night of the Living Dead was made. If Night of the Living Dead wasn’t so frightening in its depiction of a humanity nearly beyond redemption, then it might have played simply as scathing satire. How else is one to understand the grim coda to the film in which the hero, Ben, played by black actor Duane Jones, survives the zombie attack on the Last Redoubt, only to be shot dead by a lynch mob of Good Ol’ Boys looking for more of ‘them’ to slaughter? If anyone was in any doubt as to Romero’s critique of humanity’s continued inhumanity to man, then the message is rammed home with the closing shots of grainy photographs of zombie kills invoking the pictures lynchers would take of their black victims.

Romero’s zombie films were always clever, but they weren’t subtle. His 1978 follow-up, Dawn of the Dead, turns the zombie into an all-too-literal metaphor for the stultified masses, their brains deadened by empty consumerism and babbling media (the radio and TV play a significant role in Night of the Living Dead, too, as a source of misinformation and un-enlightenment). Hence the most famous scene in Dawn of the Dead, a film in which survivors hole up in a shopping mall in post-industrial Pittsburgh, features zombies trundling around a department store to a muzak accompaniment.

The zombie here channels a fear of the levelling down, and devalorisation, of Western life, its abysmal emptiness come to consume what’s left of the citizenry. The barbarians are no longer to be found at the gates – they are undying in our nihilistic, consumerist midst. It is but one short step from fearing (and loathing) braindead Westerners caught in the vice of a seemingly soulless capitalism to sympathising with, and supporting, the vehicles of their comeuppance. Which Romero does in the Day of the Dead (1985), with its almost moving portrait of the zombie Bub, and Land of the Dead (2005), which pits a put-upon, but increasingly class-conscious zombie army against an evil high-living capitalistic elite.

But, as epochal as Romero’s cultural contribution was, transforming the zombie into one of the most potent symbols of the West’s loss of faith in itself, its self-induced descent, its self-loathing given a once-human form, he was never going to stop the zombie from undergoing further cultural mutations. It was almost as if the genre left him behind, as seen from his complaints about the incredibly popular TV series The Walking Dead. The metaphor moved on, and literally sped up, given the alacrity with which zombies were to move in the 2004 Zach Snyder remake of Dawn of the Dead, or the Brad Pitt-fronted zombie epic, World War Z. But Romero’s influence, his cultural achievement, is undeniable. Few before and since have infused the zombie with as much cultural and artistic vitality as Romero did. Thanks to him, the zombie lives on.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Ben Templesmith, published under a creative commons license.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.