When football clubs are more progressive than feminists

Sheffield United should be cheered for taking back Ched Evans.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

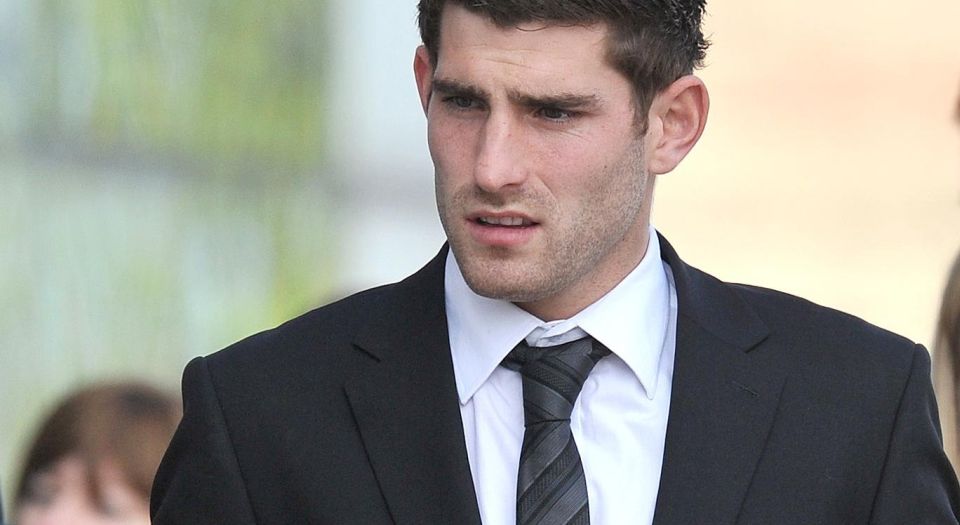

And, with a short statement on the Sheffield United website, in which he said he was ‘delighted’ to be back, that was that. Ched Evans, a name long sunk in mud, is now a United player again.

But this should have been allowed to happen three years ago, when he was first released from prison having served half of his five-year sentence for rape. That was what United wanted to happen, as did Evans himself. He was now an ex-con, of course, but he was also free — free to show that he’d changed, reformed, rehabilitated. But too many desired a different outcome. They didn’t want Evans to be able to restart his life. They didn’t think he ought to be free. They didn’t believe that he had been punished enough – perhaps they thought he could never be punished enough.

So they petitioned and they clamoured and they lobbied. Columnists said things like, ‘men who have raped… need to see their lives reduced to ash’, or ‘can we afford to reinstate Evans in his position of enormous privilege without a backward glance?‘. And sponsors and club patrons threatened to cut ties with any football team tainting themselves by association with Evans.

So, in 2014, United withdrew the contract offer to Evans, as did Oldham Athletic a few months later. No one would touch Evans such was their fear of the wrath of his persecutors. In fact, it would take another two years for Evans finally to find a club – League Division 2 side, Chesterfield Town – but even then that was only after Evans’ conviction had been quashed and a retrial ordered.

For too many, Evans just didn’t deserve a second chance. He was not seen as worthy of redemption, or deemed capable of rehabilitation. It was not enough to punish him for what he did. He needed to be punished for what he was — namely, a rapist. By having what was deemed non-consensual sex with a woman (and the case was always murky), he had broken the law, and, deeper still, in a moral climate oriented around protecting the vulnerable, be they woman or child, he had sinned. He had revealed himself under the feminist gaze as what he was and is, and, perhaps at some level, what all men potentially are. He was therefore evil. Satanic, almost. The very worst of human nature. And as such, no punishment could ever be enough. Except perhaps eternal damnation, which is effectively what his persecutors wanted.

Of course, some argued that Evans’ treatment would not have been as punitive if he had at least showed some contrition. But then he didn’t believe he was guilty. This was why, right from the moment he was first convicted, he and his legal team were trying to appeal the verdict. To have expressed contrition would have made this appeal impossible because it would have meant admitting his guilt. After all, you can’t be sorry for something you haven’t done. And last year vindication arrived. The Court of Appeal quashed the original conviction in April, and, following a retrial at Cardiff Crown Court, he was acquitted.

But the odour clings to his name. Last year, campaigners and officials acted as if the judges and jurors who cleared Evans had done something wrong. Vera Baird, the Northumbria police and crime commissioner, claimed the acquittal ‘set [the justice system] back 30 years’. Meanwhile, the charity Rape Crisis said the case would prevent complainants reporting to the police. It seems, Evans’ stigma, his shame, his disgrace, will outlast him. Which is hardly a surprise. The Evans case was never about justice. Rather, it was about a symbolic, extrajudicial punishment, a revenge upon Evans for the sins of man; a punishment not for his action, but for his being.

He turns 29 later this year. As United’s co-chairman Kevin McCabe admitted, his ‘best’ years as a professional footballer are nearly over. But, despite the whiff of sulphur that hangs around the name of Ched Evans, Sheffield United have at least shown themselves willing to treat him as a human being, not an avatar of evil, just as they did when the guilty verdict still stood. The cynic will say that they have always had considerable motivation for doing so, given his worth to them, both as a commodity to be sold, and a player who scored a lot of goals. All this is true. But in always being willing to give Evans a second chance, United have proved themselves far more progressive and humane than those who persistently, shrilly gave him no chance at all.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.