In defence of the Thirteenth Amendment

It’s a lie to say it didn’t really abolish slavery.

On the first day of February, which is National Freedom Day and the start of Black History Month in the US, vice president Mike Pence tweeted that he was commemorating Abraham Lincoln and the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. He received a flurry of criticism.

To many, the Thirteenth Amendment is not worthy of celebration because of its clause saying the ban on involuntary servitude does not apply in prisons. Involuntary servitude is outlawed, it says, ‘except as a punishment for crime’. Some, like Vibe magazine, argue that the Thirteenth Amendment contributed to the mass incarceration of black men in America today. This is why, Vibe says, Pence’s tweet ‘rubbed many online the wrong way’.

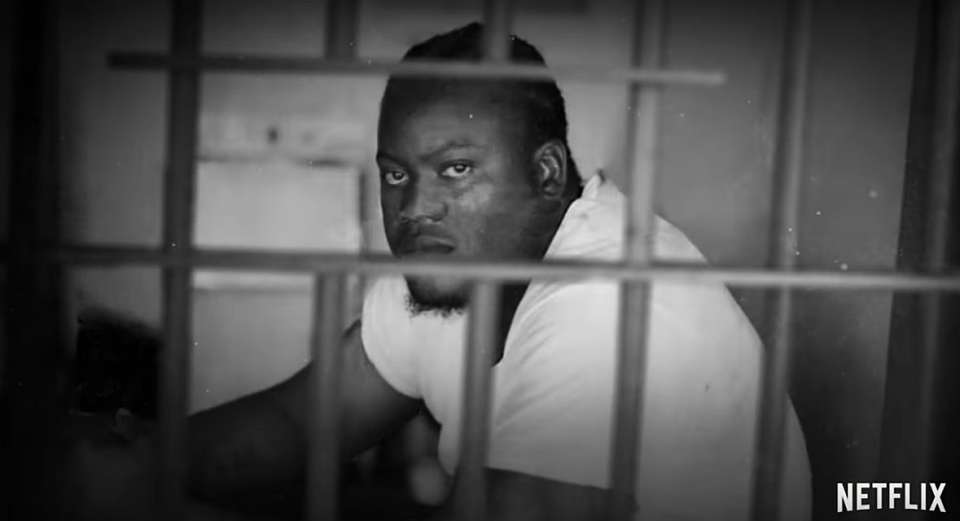

This is all part of an increasingly popular reinterpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment. Thanks in large part to Ava DuVernay’s recent Netflix documentary, The Thirteenth, the idea that this amendment stored up huge problems for the future has been gaining ground. DuVernay herself replied to Pence’s tweet, informing him that she had shown through her film that the importance of the Thirteenth Amendment is largely bunk.

DuVernay’s documentary says the Thirteenth Amendment didn’t actually abolish slavery in America. Through its clause allowing for penal servitude, blacks remained enslaved – first through unfair arrests and convictions in the South in the late 19th century, and then nationwide as a result of the war on drugs in the late 20th century. This view of the Thirteenth Amendment is now widely accepted among activists. As the anti-police brutality activist Shaun King says, the amendment’s wording is one of ‘the greatest conspiracies in American history’.

Rather than abolishing slavery, the Thirteenth Amendment gave slavery ‘constitutional protection’, which has ‘maintained the practice of American slavery in various forms to this very day’, says King. ‘Those words aren’t about ending slavery, but are shockingly about how and when slavery could receive a wink and a nod to continue’, he claims.

This new interpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment needs to be challenged. Because it completely ignores the motivations behind the amendment’s passing, and why that particular wording was chosen.

It’s true that African-Americans faced racial oppression for a long time after the passing of Thirteenth Amendment, including from law enforcement. However, despite the fashionable new view of the Thirteenth Amendment, the fact is that it was created with the explicit intention of not allowing slavery to continue after the end of the Civil War and never allowing it to return in the future.

In 1864, with the Civil War turning in the Union’s favour, James F Wilson, a congressman from Iowa, asked: ‘Is it not madness to act upon the idea that slavery is dead?’ Thousands still remained in bondage in the Border States. There was still a strong prospect of Southern states reviving slavery. Worst of all, would those freed through the Emancipation Proclamation be returned to property status?

This fear of slavery’s revival consumed abolitionists and Republicans as the war was coming to a close. Lyman Trumbull, an Illinois senator and one of the key partisans for the Thirteenth Amendment, expressed this fear: ‘There is nothing in the Constitution to prevent any State from re-establishing [slavery].’

The institution of slavery had always been sanctioned at local, state level. Prior to the Civil War, abolitionists had accepted that the constitution, in its current form, did not give them license to abolish slavery – much as they wished it did. While the constitution did not recognise slavery as an institution at a national level – the category of ‘slave’ is not mentioned in the document – slavery could nonetheless exist as a result of ‘positive’ laws created at state level.

And the constitution did not allow for national government to meddle in such state law. So the fear was that the same constitutional protection of the right of states to enact laws would return once the war was over. Slavery would return in the South.

Wilson concluded that slavery had been condemned but not executed. ‘Why should we not recognise the fact and provide for the execution?’, he asked. Republicans drafted a flurry of proposals in an attempt to carry out this execution. Some proposed criminalising re-enslavement. Others suggested reducing the defeated South to ‘territory status’, which would have given the federal government the right to override certain laws and abolish the institution of slavery.

Eventually, a consensus emerged that the surest way to defeat slavery was to amend the constitution itself. A constitutional amendment would, in Trumbull’s view, ensure that ‘not only does slavery cease’, but that ‘it can never be re-established by State authority’. These aren’t the words of a man hoping to reintroduce slavery by the backdoor, or offering a wink to anyone who wished to do so.

And so an amendment was made to the US Constitution: ‘Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.’

Even the wording of the clause that has become the subject of so much controversy – ‘except as punishment for crime’ – was chosen with the express intention of preventing slavery’s return. The text of the amendment is lifted from a portion of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance. This was no coincidence. This ordinance successfully prevented slavery from taking root in the lands west of the Appalachian mountains and north of the Ohio River. The ordinance, with its simple and clear language, was credited with preventing slavery from ever becoming established in these states. As a result, it held a special place in the hearts of abolitionists, and so they adopted it.

As the historian James Oakes points out in his book Freedom National, ‘Among political abolitionists and anti-slavery politicians, particularly in the Midwest, the ordinance of 1787 was the touchstone of anti-slavery constitutionalism. It was widely believed that thanks to the ordinance there was no slavery in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, or Wisconsin.’

Rather than the wording of the Thirteenth Amendment being cynically and carefully chosen to allow for the perpetuation of slavery, in fact it was copied from a law whose successful application acted as a block on slavery.

None of this, of course, is to deny the continued oppression blacks faced after the war. Betrayal by the northern elites meant blacks suffered under lynch mobs and Jim Crow laws for at least another century. Yet even as we recognise this, we can surely still celebrate the noble and humanist sentiments behind the Thirteenth Amendment.

Many take a misanthropic view of history today, always seeking out the hidden agendas or secret lack of principle among those we consider great men. But the truth is that the Thirteenth Amendment was a great moment in American history, and it meant that blacks could never again be the legal property of whites. The very reason the US government has a day committed to celebrating the amendment – National Freedom Day, when Pence tweeted – is down to the advocacy of one Richard R Wright, who was born a slave in 1855 and given legal freedom by the Thirteenth Amendment.

Tom Bailey is a spiked columnist.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.