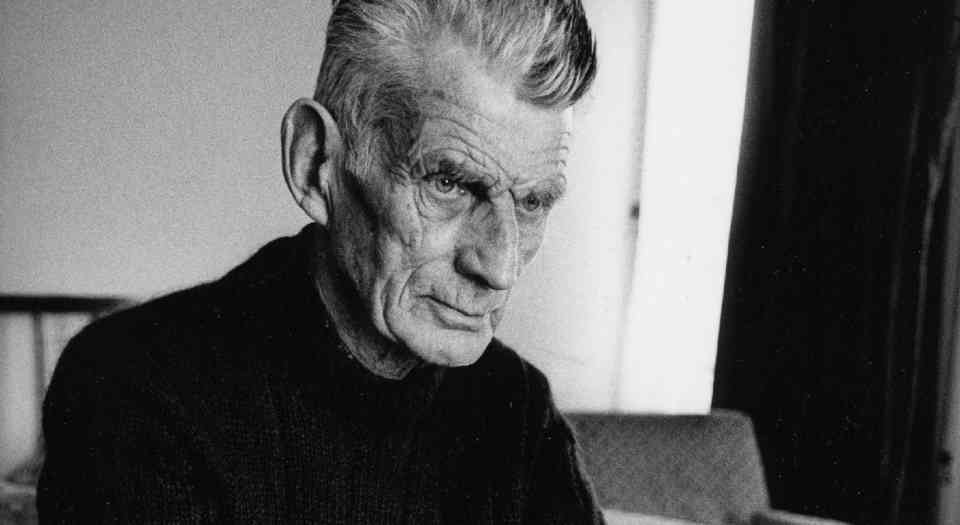

Samuel Beckett: a man of letters

Beckett’s letters reveal a personality inseparable from the act of writing.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

There are few figures in modern literature as enigmatic as Samuel Beckett (1906-1989). His dramas Waiting for Godot and Happy Days present characters in predicaments equally pitiful and grotesque. His novels such as Murphy, Watt and Malone Dies give internal monologues of characters trapped in webs of memory and doubt. These works are quintessential examples of existential literature, though they have been described as absurdist. He was famously resistant to exegesis and refused to explain what his writings ‘meant’, a stance which generated exasperation and admiration in equal measure from detractors and supporters. ‘I know no more of the characters than what they say, what they do and what happens to them.’

A collection of approximately 2,500 letters, postcards and telegrams fills the 3,500 pages of the recently completed four-volume set, The Letters of Samuel Beckett. Beckett, and later his estate, stipulated that the only letters to be published should be those directly addressing his work. Yet it would be incorrect to say the selection neglects the personal because writing described and defined Beckett’s outlook on life. As readers of his novels notice, there is often an overlap between the fiction and the events in Beckett’s own life.

After studying in Dublin and Paris, in the winter of 1936-7, Beckett toured the museums of Germany. ‘The trip is a failure. Germany is horrible. Money is scarce. I am tired all the time. All the modern pictures are in the cellars.’ He had introductions to artists who, having been forbidden by Nazi authorities to exhibit or publish their work, were living under conditions of living death. A close friend was the poet Tom MacGreevy, later director of the National Gallery in Dublin, and art is a constant subject throughout Beckett’s correspondence. Beckett’s enthusiasm for art meant that he came into contact with many artists and formed strong friendships with some, including Jack B Yeats. He bought art and also wrote brief catalogue essays to support his favourite artists.

The development of literature might have been different had Beckett’s application for a place at the Moscow state school of cinematography been accepted. His rather casual letter to Sergei Eisenstein is printed here. Instead of pursuing a career in cinema, teaching or academia, Beckett published fiction before the Second World War. Beckett’s first published novel, Murphy, almost became a posthumous publication. In January 1938, while the book was in the proofing stage, Beckett was stabbed in a Paris street by a drunk. He made a full recovery and in letters to friends he downplayed the risk his life had been in.

During the war Beckett was part of the French resistance. There are no letters between the German invasion in 1940 and the liberation of 1944. Again, Beckett downplayed his wartime activity. The fear of wartime France and shortages in power and food mark the immediate postwar years, a time when Beckett was at his most productive.

Like Joyce (whom Beckett knew), Beckett had deep roots in Ireland and his language is rich in Irish inflections, but he disliked the insular nature of Irish society. Beckett commented on a Modernist painting being ‘attacked with spits and sticks’ in a Dublin gallery. He was indignant when the Catholic Church added his books to the list of banned books, and when his plays were deemed too blasphemous and vulgar to be performed in his native country. He was also disgusted to have to bowdlerise his plays to get them approved by the Lord Chamberlain for stage performance in London.

The award of the Nobel Prize to Beckett in 1969 was called by Suzanne, Beckett’s wife, ‘a catastrophe’. She gave Beckett’s view of prizes. ‘What he dreads above all, in the very unlikely event of his receiving a prize, is the publicity which would then be directed, not only at his name and his work, but at the man himself.’ He himself mentioned ‘the threat of this prize’, which he said beforehand that he did not want but would not refuse. When the flood of congratulations arrived, the author felt compelled to answer the 500 messages personally.

The demands of fame intensified Beckett’s proclivity for silence and privacy. He divided his time between an apartment in Paris and a country cottage in the dank cheerless village of Ussy-sur-Marne. He wrote less, wrote shorter, published more infrequently. Characters lose names; speech dries up; the simplest of gestures become all that is left. The final plays are short and formidably austere. While painters rarely run out of material, writers often do, especially if they are engaged by themes more than plots. Beckett’s mature work is essentially plotless and describes conditions and states rather than any evolving story. His last plays become closer to performance art or dance than they do to drama. Then there was the tedious and taxing translation of his own texts to and from English and French.

There is much that is enlightening in the letters regarding the plays. In communications with actors, directors, agents and, later, academics and biographers, Beckett explains the meaning of obscure references and guides staging even though he never suggests the motivations of characters. Asked for advice on staging Godot, Beckett wrote: ‘I have no ideas about theatre. I know nothing about it. I do not go to it.’ Contrarily, he also commented, ‘In Godot it is a sky only in name, a tree that makes them wonder whether it is one, tiny and shrivelled. I should like to see it set up any old how, sordidly abstract as nature is, for the Estragons and Vladimirs, a place of suffering, sweaty and fishy, where sometimes a turnip grows, or a ditch opens up.’

The letters discuss art, music, literature, culture and travel. Beckett discusses his health, consoles the bereaved and (rarely) touches on current events. They range widely in tone and are rich and warm, often funny, belying the taciturn image of the author. They unlock some secrets and show Beckett more openly than ever before.

The annotation is thorough and biographical notes are provided for the main recipients. Many individual paintings, books, concerts and articles have been identified, though the annotations can provide some unintended absurdity: ‘Mary Manning Howe’s joke about WB Yeats is not known.’ Overall, the editors have balanced information with restraint. The selection and editing is excellent, and the letters are presented in their original language and translated into English when they are in French or German.

As Beckett’s health and energy diminished, and the claims on his time became more numerous, so his letters became shorter and shorter. Until, at the end, there are no letters longer than a few sentences. ‘I am searching for a way of capitulating without giving up utterance – entirely.’

‘I can’t go on. I’ll go on.’

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer. His latest book, Letter About Spain, is published by Aloes.

The Letters of Samuel Beckett: Volume 4, 1966-1989, by Samuel Beckett, (and edited by George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn and Lois More Overbeck), is published by Cambridge University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK)).

Picture by: Pere Ubu, published under a creative commons licence.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.