Long-read

In defence of ‘the poorest hee’

The brilliant democratic cry of the Levellers remains unanswered.

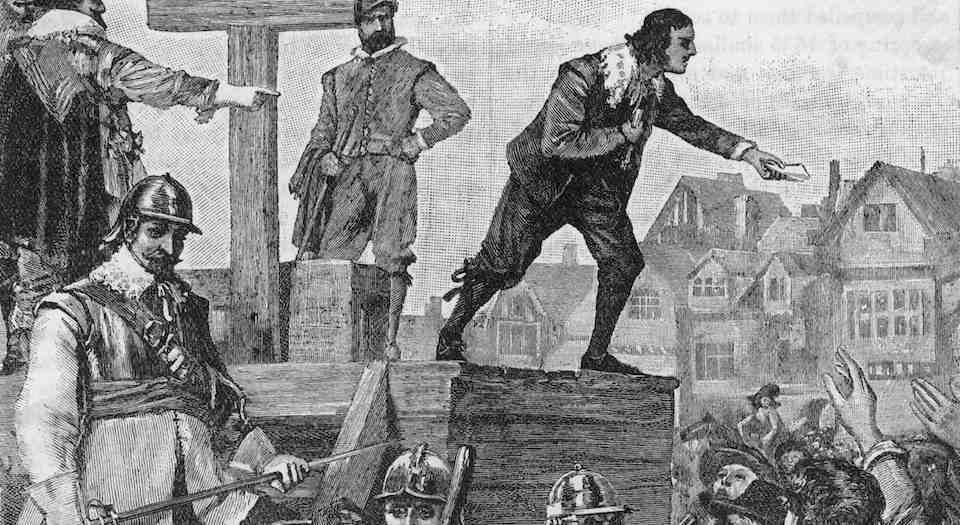

It is arguable that democracy as we know it, the modern, much fought-for ideal that a people should be sovereign over itself, was born in a pokey church in Putney in south-west London. There, in St Mary’s, by the Thames, members of the New Model Army that fought on the side of parliament against the king in the English Civil War met in 1647. They spent 15 days, from 28 October to 11 November, discussing the constitutional set-up of a new, freer Britain, the fate of the king, and the idea, put forward by more radical attendees, that there should be manhood suffrage — that is, one man, one vote; a parliament elected by all men, including poor men. For two weeks the church fizzed with ideas and proposals that would reverberate not only across Britain, but around the world, inspiring American revolutionaries, French revolutionaries and others to depose of rotten regimes and stagger towards democracy. The church is still there, and emblazoned on its wall is perhaps the key cry of the more radical elements who gathered in it 350 years ago: ‘The poorest hee that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest hee.’

‘The poorest hee hath a life to live as the greatest hee.’ It was a plea for the franchise for all men, regardless of station or wealth or even intellect. The words were uttered by Thomas Rainsborough, an MP for Droitwich in Worcestershire and a leading spokesman for a group called the Levellers in these Putney Debates, as history has recorded them. Rainsborough continued: ‘I think it clear, that every Man that is to live under a Government ought first by his own Consent to put himself under that Government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that Government that he hath not had a voice to put Himself under.’ It was a searingly radical idea then, and arguably remains radical now: that even the poorest, least well-educated person should not be ruled by any institution whose existence he has not in some way consented to. It was the expression of a new idea — or rather of an old idea stretching back to Athens, but lost for millennia, in a new form. And it’s no exaggeration to say, as one historian does, that this proposal in a church to enfranchise ‘the poorest hee’ became ‘the spark that was to light the fire which eventually razed centuries of tyranny, monarchy, feudalism and oligarchy’, not only in England, but beyond (1). Around the world, ‘the poorest hee’ forced himself into public life, rudely intruded on history, remade the political world.

The Levellers were not an especially coherent group on the parliamentarian side in the Civil War. They were also not the most radical body in this most brilliant and tumultuous of periods in English history. The Diggers, for example, a collection of Protestant radicals who called themselves True Levellers, went further in terms of agitating for a wholly open politics and even economic equality. But the Levellers’ case for democracy, and for the thing that is essential to democracy, freedom of the press, stands as the most articulate and long-lasting cry of the Civil War. It’s also an unanswered cry. It helped to raze tyrannies, and moved millions, yes, but it remains unfulfilled. The Levellers’ proposals, or questions, on how the sovereignty of the people should be embodied and exercised, and why all ‘hees’, not just the ‘greatest hee’, should get to steer the fate of the nation, and why press freedom must be unfettered and unpunished if we are genuinely to have an open, democratic politics, remain unsettled, remain unresolved. Indeed, events of 2016, in particular the rash, unforgiving reaction of the elites to Brexit and the ill-educated ‘hees’ who voted for it, show that the ideas pushed by the Levellers in that church 350 years ago are still controversial; they’re the unfinished business of history brimming under the terra firma of our polite politics; they’re yet to be won.

The English Civil War was in fact three wars, which took place between 1642 and 1651. They were wars over the manner of government in England, pitting parliamentarians, or Roundheads, against royalists, or Cavaliers. Their impact was extraordinary. There was the execution of Charles I in 1649. There was the complete replacement of the monarchy with a Commonwealth of England from 1649 to 1653, and then a Protectorate from 1653 to 1659, through which Oliver Cromwell, the key commander of the parliamentarian forces, and later his son became Lord Protector — effectively dictator — of England, Scotland and Ireland. In 1660, the monarchy was restored, with Charles II put on the throne; but his successor, James II, was then deposed in 1688 by the specially arranged coup of an invasion of England by the Protestant William of Orange from the Netherlands, who ruled under terms set by parliament. These terms imposed dramatic limits on royal power. And so, following years of conflict and monarchical rearrangement, was the supremacy of parliament established.

But it is what the Civil War years of 1642 to 1651 unleashed in terms of public debate and argument and scorching radicalism that is most striking, and which should speak to us still. It was, to use the title of historian Christopher Hill’s book on the wars of the 1640s, ‘The World Turned Upside Down’. The explicit calling into question of the traditional structures of authority nurtured a new daringness of thought. It unleashed ideas that had not been expressed before, at least not openly. And not only in that church where the New Model Army gathered in 1647, but also in pubs, workplaces, and on the streets, where a culture of pamphleteering and propaganda took hold as all sorts of groups sought to stir up the populace and win support. The collapse of the old authority meant that a ‘lower-class heretical culture burst into the open’, says Hill. Hill reckons this heresy against the elite had ‘an underground existence’ for decades, back to the late Middle Ages, but in the 1640s, following the abolition of the Star Chamber in 1641 and the de facto end of censorship, such heresies could be published and shared and discussed like never before (1). (Parliament, through the Licensing Order of 1643, replaced the royal censorship of the Star Chamber with its own political censorship. But it was not enough to prevent an explosion in pamphlets and newspapers: between 1640 and 1660 more than 300 news publications emerged.)

The result of the collapse of the old forms of authority, in Hill’s words, was a period of ‘glorious flux and intellectual excitement’. There was an ‘overturning, questioning, revaluing of everything in England’ (2). Most striking was the rejection by ‘the poorest hee’ of the idea that it should fall to the Latin-speaking, university-educated clerical caste to ‘hand truths down’ to people. As one historical account says, the more radical sections in the glorious flux of the 1640s ‘violently rejected the notion that a university education and a facility in Latin, Greek and Hebrew conferred superior spiritual knowledge upon a separate clerical caste’ (3). Fuelled by the ideas of the Reformation, it was an early agitation against expertise, of the spiritual variety, and an expression of trust in oneself and one’s own moral and spiritual capacity. The overturning of everything in England threw open the question of political authority and religious authority, and created the space for an unprecedented period of thought experimentation, radical debate and, of course, conflict. It opened up the possibility that people could think for themselves and govern themselves. It opened up the possibility of democracy.

Into this glorious flux, and facilitating this glorious flux, came the Levellers. Consisting of the most radical elements of the New Model Army, MPs, pamphleteers and activists, the Levellers agitated for the fulfillment of the radical promise of the 1640s. Their key document was ‘An Agreement of the People’. Drafted by Agitators of the New Model Army and civilian Levellers, in October 1647, as the gathering about England’s future took place in Putney, the agreement feels as fresh and radical today as it must have done back then. We ‘do declare and publish to all the world’, the Levellers said, conscious, perhaps, of the likely global impact of their radical stab for the democratic rights of all men, that the ‘Supreme Authority’ of England shall rest in a ‘Representative of the People’ — that is, a freely elected parliament.

They put restraints on parliament, too. It must not, they decreed, interfere with freedom of religion, force any man to join the military, or exempt anyone from the normal course of law. Article 10 of the agreement is a stirring statement of faith in freedom over political authority: ‘[W]e do not inpower or entrust our said representatives to continue in force, or to make any Lawes, Oaths, or Covenants, whereby to compell by penalties or otherwise any person to any thing in or about matters of faith, Religion or God’s worship or to restrain any person from the profession of his faith, or to exercise of Religion according to his Conscience.’ Parliament was to be the supreme authority in politics, representative of the people, but not in people’s beliefs or faith or speech. If this agreement outlining the right of the people to choose their representatives and limiting the power of parliament in matters of conscience and thought sounds familiar, that’s probably because it was a key inspiration for the American Bill of Rights, almost 150 years later, which likewise limits the power of officialdom in matters of belief and speech. ‘Congress shall make no law…’ — an echo of ‘We do not inpower our said representatives…’

The agreement went through various drafts in 1647, 1648 and 1649. The final version, of May 1649, signed by leading Levellers John Lilburne, Richard Overton, William Walwyn and Thomas Prince, is one of the great documents in history. It insists upon the right to vote (for men over the age of 21, excepting servants, beggars and royalists); the equality of all people before the law; the right to trial by jury; the right to silence during trial; severe restrictions on the use of the death penalty; an end to imprisonment for debt; an end to military conscription; and an end to the official persecution of or prejudice against people ‘for any opinion or practice in Religion’. In the late 1640s, this agreement was distributed and devoured across the nation. Levellers had their own weekly newspaper. They and their supporters met in taverns. As one historical account says, the tavern, with men ‘discussing the affairs of the day over a tankard of ale or a glass of sack’, had become ‘an important political institution’ (4). It is notable that, unlike other, more religiously inclined radical groups in the Civil War, ‘No Leveller petition ever included among the reforms it demanded the repression of swearing and drinking… or the stricter observance of the Sabbath, or the banishment of fiddlers from the taverns’ (5). Already, long before they finally won the right to vote in the 1800s, and for women the 1900s, the ‘poorest hee’ was engaging in politics, governing his own thoughts and beliefs.

But the agreement was not to be. It did not, of course, become the new constitution of Britain. It was too radical for Cromwell and other leaders of the New Model Army, and the Levellers were crushed. Indeed, when the final version was published in May 1649, Lilburne, Overton, Walwyn and Prince had already been imprisoned. In that same month, a Leveller mutiny in the ranks of the New Model Army was crushed at Burford in Oxfordshire. The Levellers were effectively finished as a political force. On 25 May 1649, Cromwell reported to parliament on his ‘successful suppression’ of Leveller elements in the New Model Army.

There were many, flaring points of conflict between the radical, Leveller sections of the parliamentarian side and its more conservative leaders. A key one was the issue of parliamentary sovereignty. Like all sections of the parliamentarian army, the Levellers believed that parliament ought to be the greatest political authority. But they viewed it as simply the expression, and an imperfect one at that, of a more supreme form of authority: that of the people’s will. The Levellers insisted that the power of parliamentary representatives is ‘inferior only to theirs who choose them’ — that is, to the power of the people, or the electorate (6). This is why the Levellers insisted on restraints on parliamentary power, arguing that its authority ought only to ‘extend to the enacting, altering, and repealing of laws’ and forbidding it from passing laws on matters of religion or conscience or any law ‘destructive to the people’s well-being’. And it is also why so many of the Levellers’ pamphlets and documents sound so agitating — they always have titles that include words like ‘petition’, ‘call’, ‘demand’, the suggestion being that pressure must always be put on parliament by those whose authority is more supreme than parliament’s: the people. This disturbed Cromwell and others, because they feared it was a recipe for anarchy. They feared that the Levellers were implying that the people’s will was not only the method through which parliament should be selected but was also superior to parliament, and that this contained in it the possibility of conflict between the people and their representatives.

And they were right to think this. Radical documents of the time raised the possibility that, were parliament to go against the people’s wishes or pass a ‘destructive’ law, then the people ‘may resume — if ever yet they parted with a power to their manifest undoing — and use their power so farre as conduces to their safety’. The Levellers even proposed that if the ‘people’s agents’ were to act against the people’s interests, then the power entrusted into parliament ‘returneth from whence it came, even to the hands of the [people]’ (7).

Power ‘returneth from whence it came’ — it was fundamentally this, this suggestion that parliament is inferior to the people, this radical idea that would later find expression in the Second Amendment to the American Constitution with its insistence on the right of people to bear arms for ‘the security of a free State’, which most perturbed Cromwell and blew open differences of opinion on parliament, sovereignty and the role of the people. The Levellers were hinting at, if not implicitly inviting, a people’s overthrow of parliament if it went against their wishes. For what the Levellers were agitating for was not simply parliamentary sovereignty, though they supported that against the monarchy, of course, but popular sovereignty. As American constitutional expert Michael Kent Curtis has argued, the Levellers ‘saw parliament as representing the people’ but they also considered it ‘distinct from the people’. They argued that, even with a free and fair parliament, ‘organising the popular will’ would be essential. And, in Curtis’s words, to Cromwell and others these efforts to organise the popular will ‘were improper because they appeared to suggest a centre of power beyond parliament’ (8). This was the crux of the Leveller / Cromwellian conflict within the parliamentarian camp: where did power lie — in parliament, or with the people?

This is not mere history. On the contrary, it is many ways the unresolved question of both Britain and much of the Western world, and of the entire modern democratic era. Where does power lie? Who or what is sovereign? Who rules, and by what kind of consent? Should the democratic process be representative and measured, or direct and popular and involving the beliefs and passions of the ‘poorest hee’ as much as of those sections of society who consider themselves better cut out for decision-making? The Western world opted for representative democracy, but we mustn’t forget that this was built on the intellectual or military defeats of others who argued for more popular forms of sovereignty, not only in England but in America and France, too. And this question has come back to life this year, with great power and urgency, in the discussion over Brexit and who should decide whether or how it happens: the 17.4million who voted for it, or our elected representatives? The people or MPs? The popular will or its representative agents?

Indeed, the Levellers’ great fear — of parliament overriding or harming the people — has become an explicit factor in daily political discussion in Britain in 2016. Members of the political class and media elite now openly agitate for parliament to ignore the people, in particular over Brexit. Parliament is sovereign, they argue, and must have the final say. MPs must ‘save us from [the] ruin’ of Brexit, says a writer for the Guardian. Geoffrey Robertson QC says MPs should ‘vote down Brexit’ because nothing ‘requires our sovereign parliament to take a blind bit of notice of [referendums]’. (This is the same Geoffrey Robertson who wrote a very good introduction to a published version of the Putney Debates in 2007. Tragic.) Labour MP David Lammy says it is incumbent upon MPs to ‘stop the madness’ of Brexit; ‘our sovereign parliament’ cannot usher in ‘rule by plebiscite which unleashes the “wisdom” of resentment and prejudice’, he says. Note the scare quotes around ‘wisdom’. Because of course the people are not wise at all. I cannot be the only person who, upon reading these defamations against ordinary people, against ‘the poorest hee’, and upon hearing observers insist that parliament should ignore the public’s will, thinks instantly of the Leveller cry that when parliament crosses the people then its borrowed power should ‘returneth from whence it came’. I hope that revolutionary idea fills our parliamentarians with as much dread as it did Cromwell. It should.

Democracy remains a deeply unresolved issue. We have it, and yet we don’t. We live under systems in which we get to vote, and that is incredibly important, but also systems in which our convictions and ideas are continually filtered, and often ignored. Is that good enough? Surely the Leveller idea of a supreme but curtailed parliament, a restrained institution that may not interfere with conscience and may never cross the people without instantly losing its authority, is better? Popular sovereignty, not parliamentary sovereignty?

Something incredibly important unites the tragic defeat of the Leveller idea of a petitioning, agitating popular sovereignty and today’s institution of and celebration of parliamentary sovereignty as a better means of doing politics and an often necessary tamer of the ‘resentment and prejudice’ of the public: a lack of faith in ‘the poorest hee’.

Royalists and religious leaders in the 1640s were most horrified by the Levellers’ attempted engagement of ordinary people in politics, and their suggestion that these people were fit for democratic decision-making. Marchamont Nedham, a journalist who would become something of a spindoctor to Cromwell, said the people were but a ‘rude multitude’, who ‘understand no more of the businesse [of politics]’ except that it might ‘satisfie their natural Appetites of Revenge upon the Honourable and Wealthy’ (9). Most strikingly, Nedham, echoing one of the key prejudices against Leveller thought, argued that entrusting the public with too much power would destroy liberty itself, ‘for the multitude is so Brutish, that they are ever in the extreames of kindnesse or Cruelty, being void of Reason and hurried on with an unbridled violence in all their Actions, trampling down all respect of things Sacred and Civill… The People becomes a most pernicious Tyrant.’ (10)

Sound familiar? The language has been toned down, and made more PC (or somewhat more PC), but the pained cries of today’s turners against democracy are virtually indistinguishable from the anti-Leveller propaganda of the likes of Nedham. This year, following Brexit, we have been subjected to relentless elite handwringing over ‘low information’ voters; panic about the dangers of politics by ‘crowd acclamation’; the demonisation of all those who dare speak of ‘the people’ as aspiring tyrants, populist authoritarians, fascists possibly, who will destroy the liberty of others; insistences that we must prevent ‘popular sentiment’ from ‘hold[ing] sway over informed decision-making’, in the words of former UN official Shashi Tharoor. It is the same argument. The same view of ordinary people as not quite right for political or public life. The same desire to shackle or at least filter popular will so that it doesn’t interfere with the ‘informed’ thinking of those who know better. It has to be said that some of the top Levellers themselves occasionally crossed the line into concern at what they viewed as the conservative instincts of much of the public, but they nonetheless considered themselves an ‘avowedly populist’ movement, as one history puts it, keen to free ‘the poorest hee’ from rule by the few and allow him to think for and speak for himself. And in essence, it is upon the repression of that Leveller idea that our modern conception of democracy is built. This is what so worried the elite about Brexit: it speaks to a more direct intervention of the people, the rude multitude, into the realm of the political; it points to a break in the elite agreement that won out over ‘The Agreement of the People’; it brings back to life hard, radical questions our rulers thought they had suppressed, thought had gone away with Cromwell’s crushing of the Levellers at Burston. It brings awkward history back to life.

In varying different ways, and even following the expansion of the franchise to working-class men in the 1800s and women in the 1900s, the belief of the elites over the past 350 years has been that ‘the poorest hee’ cannot truly govern himself, either his own mind or his community and society. Blocks, tempers and filters are enforced against what hee thinks. That line spoken by Rainsborough — ‘The poorest hee hath a life to live as the greatest hee’ — is still doubted, and still dampened down. Few believe it, certainly few in the political and cultural elites. Brexit confirms that; it confirms the Cromwellian instinct at large in our political life. Today, again, we must defend the poorest hee, and all people, and insist they have the capacity, and ought to have the right, to be individually sovereign over themselves and collectively sovereign over the society they live in. That they should be the subjects of history, not the objects of it.

The early 20th-century left-wing writer HN Brailsford, in his book The Levellers and the English Revolution, posited that leading Levellers probably did not view history as a ‘divine puppet play’ in which ‘the finger of God manipulates men on the chequer-board of destiny’, but rather saw history as something men control, if not always successfully. This is an ideal worth reasserting today: that the making of history should be open to as many people and voices and ideas as possible. That democracy should be as open and wide-ranging as possible. That sovereignty should be more popular, not less. And that the poorest hee is just as good, if not better, at making political decisions as any politician, spiritual leader, expert or member of the ‘Honourable and Wealthy’ who so feared the rude multitude 350 years ago, and still fear it today.

Brendan O’Neill is the editor of spiked.

(1) The Book of Books, Melvyn Bragg, Hodder & Stoughton, 2011

(2) The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution, Christopher Hill, Pelican Books, 1972

(3) The English Radical Imagination: Culture, Religion and Revolution 1630 to 1660, Nicholas McDowell, Clarendon Press, 2003

(4) The Levellers and the English Revolution, HN Brailsford, Stanford University Press, 1961

(5) The Levellers and the English Revolution, HN Brailsford, Stanford University Press, 1961

(6) Empire of Liberty: Power, Desire and Freedom, Anthony Bogues, University Press of New England, 2010

(7) Judicial Monarchs: Court Power and the Case for Restoring Popular Sovereignty, William J Watkins Jr, McFarland and Company, 2012

(8) Free Speech, the People’s Darling Privilege, Michael Kent Curtis, Duke University Press, 2000

(9) Against Throne and Altar, Paul A Rahe, Cambridge University Press, 2008

(10) Milton and the People, Paul Hammond, Oxford University Press, 2014

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.