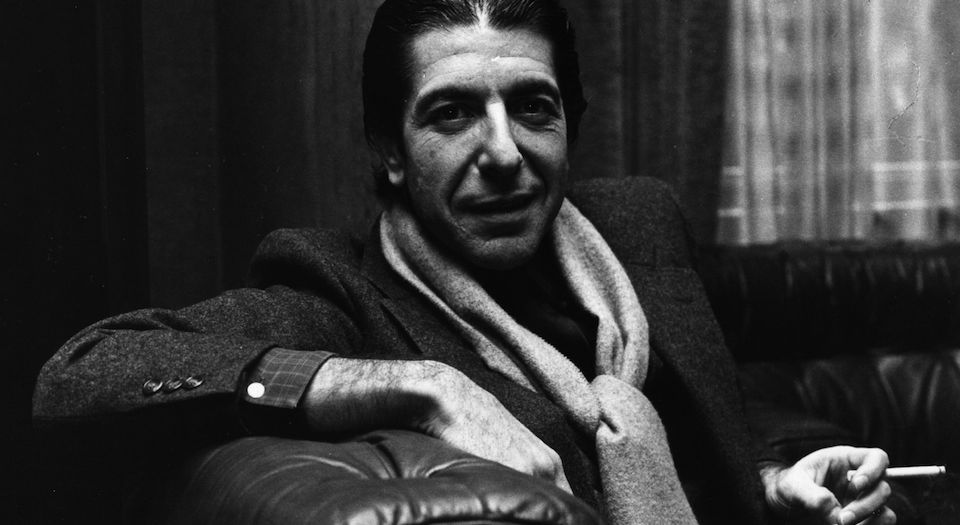

My Leonard Cohen

His songs inspired me to try to make something of my life.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It was in August 1967 that I first properly encountered Leonard Cohen. Of course I had heard of him before. In one of my seminars at McGill University, after telling us to go and read some of Cohen’s poems, my tutor proudly declared that Cohen used to study literature in our English department. I dutifully read some of his poetry, and his novel Beautiful Losers, and came to the conclusion that although he was not a great writer, he had a remarkable way with words.

In all likelihood, my engagement with Cohen would have ended when I gave up on Beautiful Losers had I not later worked as a guide at EXPO67: the world exhibition in Montreal. The best thing about working there was not the money, but the access we had to free concerts in the evenings. The night Leonard Cohen came to sing, the café was about three-quarters full. There were around 70 of us in the audience, drinking beer. It was when I saw a tear in my then girlfriend’s eyes that I realised I was listening to something very special. Cohen had just finished singing ‘Suzanne’. It was at that moment that we knew he had looked into our souls.

I spent the next couple of months hoping to see Cohen perform, but without success. Word got around the McGill student ghetto that he would soon show up at a well-known local folk club — the Café Prag — but we couldn’t find out when. I would not see him sing again until the Isle of Wight music festival in 1970, where, bizarrely, he came on stage after Jimi Hendrix.

His debut album Songs of Leonard Cohen, released in December 1967, remains his most powerful work. With that album, he gave an intensely sensual form to his poetic imagination through the medium of song. I have never heard anyone sing about human weakness and raw pain with such sincerity.

His song ‘One of us cannot be wrong’ self-consciously preys on our insecurity to remind us of a few unflattering truths. Its opening line, ‘I lit a thin green candle, to make you jealous of me’, confronts us with the uncomfortable truth that we devote far too much energy to playing games with each other.

The melancholic and at times depressing tone of some of the songs is punctuated by an aspiration for transcendence. His songs are about alienation, our estrangement from each other. But there’s always something more. ‘The stranger song’ explores estrangement with great depth and beauty. I still sing that song in my head whenever I feel sorry for myself. Cohen’s stranger might be gone before you can blink an eye, but don’t forget he is the kind of man ‘who is reaching for the sky just to surrender’. That’s the kind of guy I wouldn’t mind sharing a few drinks with.

Cohen’s second album, Songs from a Room, struck me as far more sad than his first. There’s also an undercurrent of cynicism in songs such as ‘The story of Isaac’. However, some of the songs nonetheless stand as a testimony to the artistic aspiration to capture an elusive sense of human freedom. ‘Like a drunk in a midnight choir, I have tried in my way to be free’, he sings in ‘Bird on the wire’.

Paradoxically, the song on that second album that inspired me to try to do something worthwhile with my life was not actually written by Cohen. It is an old French song, about the reaction of the French Resistance to invasion by the Germans. ‘The Partisan’ begins with the lines:

‘When they poured across the border

I was cautioned to surrender

This I could not do

I took my gun and vanished.’

This melody of defiance is tinged with the realisation that resistance will exact a very high price. And yet this person is not prepared to surrender. The song ends on a hopeful note:

‘Freedom soon will come

Then we’ll come from the shadow.’

The refusal to surrender — it’s one of the most stirring things in Cohen’s art. At times, yes, his songs draw us toward the modern purgatory of depression and disorientation, but Cohen does not surrender. Even in old age he could sing ‘First we take Manhattan’ and really sound like he meant it.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator and author of the What’s Happened To The University?: A Sociological Exploration of its Infantilisation (buy this book from Amazon(UK)).

Picture by: Getty Images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.