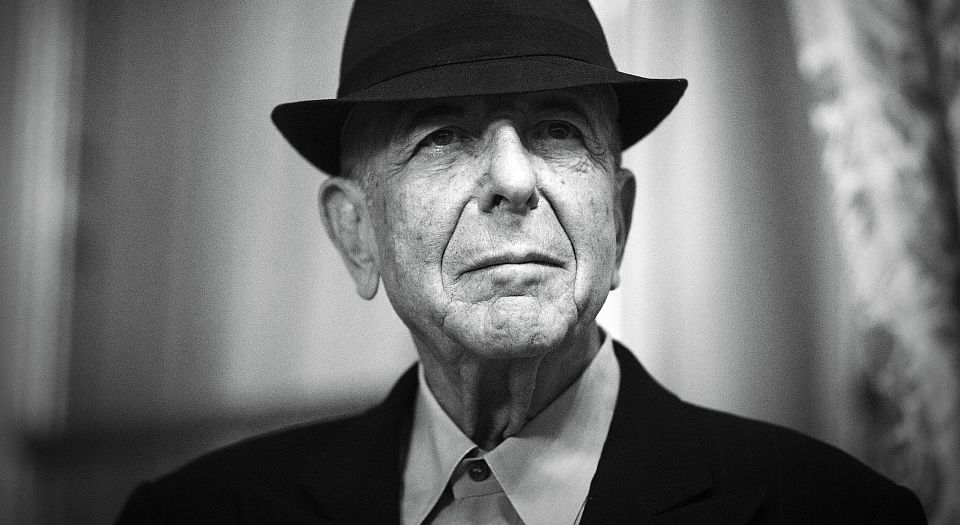

Leonard Cohen: yearning for transcendence

Cohen wasn’t the godfather of gloom; his music lifts you up.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Let’s get one thing straight about Leonard Cohen. Any fan of his work knows that his reputation for making ‘music to slash your wrists to’ is complete nonsense. Though his music is haunted by mortality, it is also deeply romantic, reverentially spiritual, daringly political, darkly sexy, and often very, very funny. His songs are deeply human, compulsively self-depreciating, and forever yearning for the transcendental.

His death, at the age of 82, makes an impact not just because he’s one of the greatest lyricists in all of popular music, but because of the astonishing intimacy of his music. Like the deaths of Bowie and Prince earlier this year, the loss of Cohen feels personal to his listeners. With his staggering 1967 debut, Songs of Leonard Cohen, he established his status as the Bard of the Boudoir. It was as if each song was personally crafted to the individual listener, Cohen’s sensual voice softly murmuring in your ear.

As the years went on, his singing voice developed into a basso profondo whisper, both soothing and authoritative – powerful with the lightest touch. While most ‘powerful’ pop singers belt at the highest ranges of their voice, Cohen found his power in the lowest depth of his vocal range.

He also had one of the most unique career paths in the history of popular music. He started out in his thirties, when he decided there wasn’t enough money to be made as a professional poet, and reached his commercial peak in his mid-seventies. But he recorded songs of immense beauty throughout his career: ‘Suzanne’, ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, ‘So Long Marianne’, ‘Tower of Song’, ‘Anthem’, and, of course, the endlessly covered ‘Hallelujah’.

Cohen’s writing bears a deep religious influence, a result of his lifelong practise of Judaism. When performing in Israel, he was known to speak Jewish prayers and bless the audience in Hebrew. He also became fascinated by Buddhism. In the late 1990s, Cohen spent five years secluded at the Mount Baldy Zen Center in California, during which he became ordained as a Buddhist monk.

His stint in the monastery led both to his financial ruin and, eventually, his tremendous late-in-life success. Kelley Lynch, Cohen’s long-time manager, abused Cohen’s trust during his time out of the spotlight. She sold his publishing rights without permission and drained his $5million pension. Cohen won a civil suit against Lynch in 2006, but it is thought that he never got his money back

Due to his financial woes, he went on tour in 2008 – his first in 15 years. It turned out to be one of the greatest ever comebacks. After all those years of building a cult following, fans congregated in their tens of thousands to hear the High Priest of Pathos. With incredible energy, Cohen performed three-hour-plus sets in arenas worldwide. Scores of reviewers hailed the shows as among the greatest they’d seen.

After returning to the scene he released three excellent studio albums. In light of his newfound success, they were the highest-charting of his career. The most recent, You Want It Darker, was released just a few weeks ago. Mixing choirs with electronic beats, the album shows that Cohen was experimenting until the end.

Although folk was the foundation of Cohen’s music throughout his career, he always had a penchant for bizarre, often incongruous arrangements. Songs of Leonard Cohen has an unusual production style. Recorded orchestral arrangements are mixed with different instruments, weaving in and out of the mix, almost at random, as the songs progress. Other oddities include the Jew’s harp on Songs from a Room and the sudden country-rock outburst on ‘Diamonds in the Mine’, a track from the gorgeously sombre Songs of Love and Hate. Even his failures were fascinating, like the fabulously over-produced Death of a Ladies’ Man, a collaboration with Phil Spector.

His most outrageous, successful arrangements, however, came on 1988’s I’m Your Man, which matched the lowest singing of his career with extravagant synth-pop, like on the bombastic, Pet Shop Boys-esque ‘First We Take Manhattan’ and ‘Tower of Song’, one of the best songs about songwriting ever written.

In the end, that song provides a better epitaph for Cohen than anyone else could write: ‘Now I bid you farewell, I don’t know when I’ll be back / They’re moving us tomorrow to that tower down the track / But you’ll be hearing from me baby, long after I’m gone / I’ll be speaking to you sweetly / From a window in the Tower of Song.’

Christian Butler is a writer based in London.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.