They Shall Not Pass: the Battle of Cable Street 80 years on

Let's celebrate the revolutionary spirit of this clash with fascists.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘Ex-soldiers asked to give way to Mosley’ was the headline in the Communist Party newspaper, the Daily Worker, on 30 September 1936. Oswald Mosley, a former Labour Party government minister, set up the British Union of Fascists in 1932, modelling it on Hitler’s Nazi Party. Chief among its tactics was the intimidation of East London’s Jews with marches and rallies, followed by violent attacks. Mosley announced that he would march through the East End on Sunday 4 October 1936.

The headline in the Daily Worker was a warning to the rebellious Stepney Communists who wanted to challenge the fascists where they marched. The party leadership hated this direct action. They wanted to draw Communists off to a peaceful march against the Spanish fascist Franco, which was planned to take place in Trafalgar Square.

On the Thursday, the Daily Worker promised that ‘Sunday will see columns of London youth marching to Trafalgar Square’. Under the headline ‘Provocation’, they warned that Mosley’s march could ‘only be construed as a provocation’. There would be a meeting in Shoreditch Town Hall that evening, after the two marches, where the Communist leader Tom Mann would make a token protest against Mosley’s incursion.

The police, the Labour Party and the Board of Deputies of British Jews also counselled that people stay away from the Mosley demonstration, for fear of promoting lawlessness.

Stepney Communists thought differently. Forbidden from challenging the fascists directly by their branch committee, they organised instead as an ex-servicemen’s association, led by Joe Jacobs. It was they, along with the radical Independent Labour Party, who organised the opposition to Mosley, along with many in the local community. Joe Jacobs had his Communist Party membership suspended for his trouble.

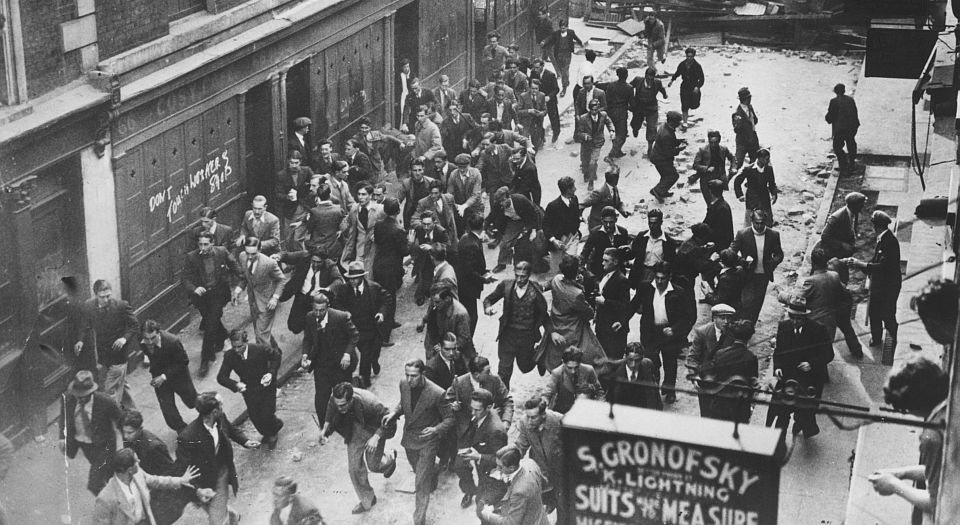

This ‘ex-servicemen’s association’ and the ordinary Jews of the East End made the difference. Their slogan, ‘They shall not pass’, captured the moment. Around 3,000 fascists turned up. Twice as many police were mobilised to support their incursion into Jewish neighbourhoods. But around 20,000 were rallied to stop them. Most of the fighting was between the police and the anti-fascists. On police advice, Mosley retreated, and the day was done. It became known as the Battle of Cable Street.

After the event, the Communist Party leadership quickly reversed its edicts against the counter-demo. It rewrote history with Stalinist determination, claiming the mobilisation as its own when in truth it had tried to sabotage it. Local Communist leader Phil Piratin was lauded as the leader of a protest he had precious little to do with.

The House of Commons was worried that ordinary people in the East End would take matters into their own hands and deal with the threat of fascism as they saw fit. The Labour Party’s Herbert Morrison went to see the home secretary Sir John Simon to demand police action. A Public Order Act was rushed through parliament to clamp down on political marches.

Today, many people in power still think of the approach of the Public Order Act, the official banning of disruptive demonstrations, as the best way to pay homage to the anti-fascists of the old East End. In keeping with this approach, left-wing groups passed ‘No Platform’ policies against right-wingers in the 1970s, and radicals still often appeal to the police to ban right-wing demonstrations today.

But the truth is that the Public Order Act was more often used against left-wingers and radicals than against the right. It was used against left-wing counter-demonstrations against fascists, Sinn Fein marches in the 1970s and striking miners in 1984/85.

What was really revolutionary about the Battle of Cable Street was that people took matters into their own hands, instead of obeying the law, the Labour Party or Communist Party officials. If they had opted to follow the instructions of the authorities and the left, Mosley would have marched unmolested through the East End, protected by the police, with the radicals safely on the other side of town. The lesson of the Battle of Cable Street is that communities should always prefer to defend themselves, with solidarity from others, rather than turning to officialdom, the law or Labour to ‘protect’ them, which too often means their independence being limited.

James Heartfield is the author of The European Union and the End of Politics, published by ZER0 Books.

Sources:

Daily Worker, 30 September 1936

Out of the Ghetto: My Youth in the East End, Communism and Fascism, 1913-39, by Joe Jacobs, 1978

Our Flag Stays Red, by Phil Piratin, 1948

Labour Inside the Gate: A History of the British Labour Party Between the Wars, by Matthew Worley, 2009

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.