Burkini wars: the rise of Francophobia

Yes, the burkini ban is wrong, but so is the demonisation of France.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It seems the burkini is this summer’s must-have. Sales are booming. Various fashion houses are in the process of designing their own lines. M&S’s new burkini stocks sold out in a matter of weeks.

The popularity of the full-body swimsuit is most likely a kneejerk response to the burkiniphobia that is spreading across Europe, and is most acute in France.

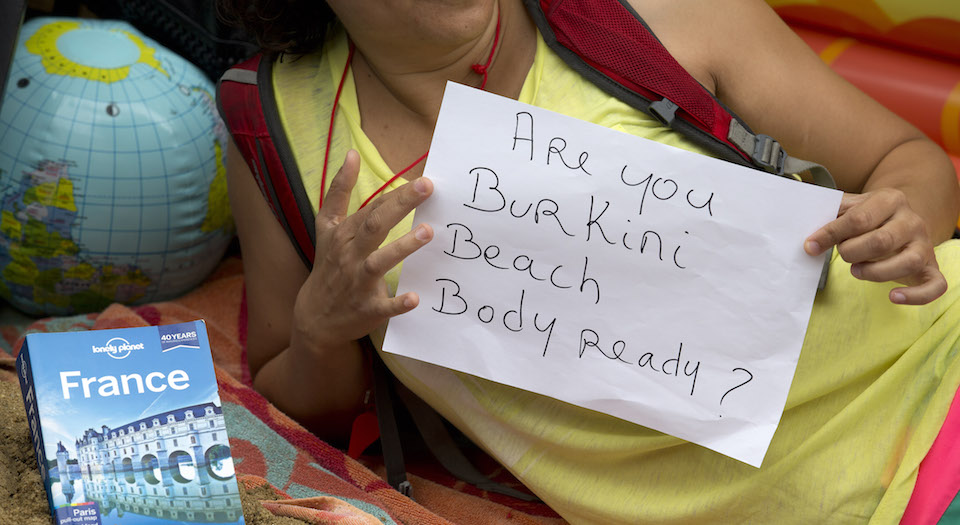

The burkini has been banned on around 30 French beaches. Those who don the swimsuit face a hefty fine. While the ban has been suspended in Villeneuve-Loubet, Cannes and Nice, the anti-burkini brigade still has momentum.

Many in the UK have criticised the ban. Right-on mayor of London Sadiq Khan condemned the French bans (seeming to forget that he recently banned adverts featuring women in swimwear from the Tube). And some pro-burkini demonstrators even organised a beach party outside the French embassy in London.

There’s no doubt that banning the burkini is illiberal. The idea that women should be punished for wearing an item of clothing pertinent to their faith is an affront to religious freedom – a freedom that, given its experience of the Wars of Religion, the Inquisition and the Second World War, France should hold dear.

With its regressive ban, France appears to be drifting away from its founding Enlightenment values. And yet, French politicians are still keen to pay lip service to them. French prime minister Manuel Valls tried to justify the burkini ban by suggesting the naked bust of Delacroix’s Marianne, a national symbol of the Republic, better represents France than the burka. ‘She isn’t wearing a veil because she’s free’, he said. For Valls, liberté clearly doesn’t apply to Muslim women.

These sentiments seem narrowminded when compared with those of 300 years ago. As Pierre Bayle, the French philosopher, commented in 1704: ‘If the number of religions prejudices the state, it proceeds not from their bearing with one another but, on the contrary, from endeavouring to crush each and destroy the other by means of persecution. All mischief arises not from toleration, but from the want of it.’

Voltaire echoed this in his 1763 Treatise on Tolerance: ‘I say that we should regard all men as our brothers.’ Crucially for Voltaire, tolerance didn’t mean nonjudgementalism: ‘I will also tell them that they are grievously wrong. It seems to me that I would at least astonish the proud, dogmatic Muslim imam.’ This is a far cry from the comments made by the mayor of Béziers last month: ‘It’s time to explain to these people that France isn’t a 10th-century Arab kingdom.’ (He’s clearly forgotten that telling women what to wear was all the rage back then.)

But while it’s easy to criticise the burkini ban, lauding our supposedly enlightened attitude to Islam over the backward French, doing so undermines any attempt to understand what caused the ban in the first place. The ban didn’t appear from nowhere. Rather, it is the externalisation of France’s internal moral and political crisis.

The emergence of Front National has been met with little effective opposition. And with Nicolas Sarkozy’s decision to lurch further to the right in his return to parliamentary politics, true tolerance is sorely lacking in contemporary French politics. The spate of terrorist attacks and the influx of migrants across the Mediterranean has left people fearful, and uncertain of what it means to be French.

People are genuinely scared, to the extent that they feel full-bodied garments are a threat to their public safety and way of life. But this won’t be solved by demonising them; rather, we ought to appreciate their concerns and seek to allay them through open-minded discussion. If there’s one tool that can counteract jihadism, and people’s resulting fears for their safety, it’s tolerance. France needs open debate about religion and migration, and a genuine attempt to grapple with what it means to be French today.

France is not a hotbed of Islamophobia. In fact, the burkini debate has revealed a certain anti-French sentiment among Western European observers. Belgium banned the burka outright in 2011. Some German swimming pools recently banned the burkini. In both Norway and Switzerland, support for a ban is growing. Yet these countries have escaped criticism.

Ultimately, the burkini ban represents a twofold crisis of values in Europe: firstly, on the part of the French, whose confusion over their founding republican values has led them towards intolerance; and secondly, there is the vacuous nature of Western values more broadly, which has led many blindly to label France as a hateful, anti-Muslim place, without looking more closely at the crisis it is facing, let alone putting forward ideas for how liberal, republican values might be meaningfully upheld today.

Reversing the burkini ban would certainly be a step towards rebuilding the Enlightenment values of toleration and cosmopolitanism. But if we really want to combat prejudice, we’re going to have to discuss the gritty subjects: immigration, the nation state, borders, religion. If women want to shield their bodies, that’s their prerogative. But we need to generate a serious discussion about what it means to be French, and European. An absence of values is far more insidious than a piece of cloth.

Jacob Furedi is a writer and student.

Picture by: Getty Images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.