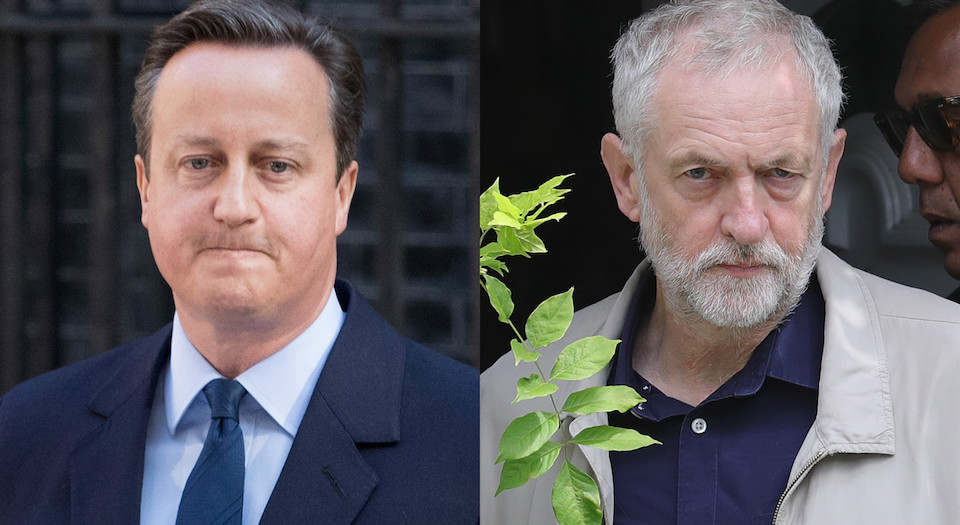

After the vote, the implosion of the political class

The referendum exposed the chasm between politicians and people.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Until the EU referendum, the estrangement of Britain’s political class from vast swathes of the public had, for politicians and pundits alike, been the source of little more than low-level anxiety. Yes, that something is wrong had often been acknowledged. But no sooner had that acknowledgement taken place than the problem had been neatly packaged up as something it’s not, be it voter apathy or public disengagement or some other piece of policymaking jargonese.

But the referendum result has shattered the political class’s coping mechanisms. It can no longer pretend that voters aren’t sufficiently interested in politics, that, at some level, it’s our fault. Too many people turned out to vote for that to wash. No, the political class is now finally having to face up to its own reality as a ruling clique, infused with a paternalistic disdain for those it can no longer claim it represents. And faced by its own image, it is now imploding, sucking in, in one last desperate back-stab for salvation, party leaders, campaign managers and anyone else at whose feet blame can be laid.

And no wonder. Commentators have been talking about the disparity between the voting patterns in London and Scotland, which both overwhelmingly voted to remain, and the rest of the UK, which voted overwhelmingly to leave. But the real disparity is between the electorate and parliament. While 52 per cent of the British electorate supported leaving the EU, nearly 80 per cent of MPs supported staying in. That means that those putatively representing people, those claiming to voice their constituencies’ interests, are no longer doing that.

The mood of the political class, and those in the media who breathe in the same atmosphere, inhaling the same entitled, right-thinking fumes, was initially just shock, bewilderment, a palpable sense of ‘how on Earth could they do this?’. ‘This morning, I woke up in a country I do not recognise’, wrote one pundit. ‘After Thursday’, wrote another, ‘I feel like a foreigner in my own country – that there’s this whole massive swathe of people out there who don’t think like me at all and probably don’t like me.’

Few actual politicians would risk admitting their distance and isolation in quite such stark, career-destroying terms. But the sentiment is there alright, in the passive-aggressive disappointment of Europhile Tories, and, more palpably, in the panicked resignation letters of Labour’s shadow ministers. So Steve Reed, shadow minister for local government, wrote: ‘A majority of Labour supporters in large parts of the north and midlands voted to leave the EU because their connection with our party has broken. We are losing touch with them…’ Anna Turley, shadow minister for civil society, echoed Reed, telling Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn that ‘it has been increasingly clear to me for some time that the leadership is not in touch with the hopes, the fears and the aspirations of my local constituents’. Quite.

Others have sought to soften the electorate’s blow to politicians’ esteem. They have emotionalised the decision of the Leave voters, turning it into a momentary spasm, a paroxysm of anger. ‘It is clear that people are angry with the political class’, wrote Labour MP David Lammy, ‘and that, with the European Union coming to represent everything that is wrong with our country, they took this opportunity to give the establishment a kicking.’ Lib Dem leader Tim Farron agreed: ‘I believe that this vote was not a vote on the European Union alone. It was a collective howl of frustration – at the political class, at big business, at a global elite.’

You can see why members of the political class would want to reduce the votes of 17.5million people to an emotional reaction, an eruption of anger. It diminishes the significance of the referendum. It turns it into something spontaneous, something momentarily irrational. It will therefore pass, as the red mist disperses, and a more reasonable, presumably pro-EU, attitude returns. But this wasn’t a temporary outburst. No, it was something positive: it was an articulation of a rational political desire. As one pollster noted, the key reason for Leavers’ vote was ‘the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK’. And in that vote, in that desire to take back a little more control over our collective lives, in that assertion of the popular will, the political class has been forced to confront its own unpopularity, its distance from the popular will.

Deep down, politicians know this. They know that their attitudes and values, drenched in a sense of cultural superiority that morphs into paternalism, are opposed to those they look down on. They know that their parties, their political vehicles, be they Tory or Labour, no longer have deep roots in wider society, their memberships having long since shrivelled from their postwar multimillion highs to below 200,000. And they know that this chasm, this profound disconnect, eats away at the legitimacy of the institutions of government. After all, former Tory prime minister John Major admitted as much in 2003: ‘All the party machines are moribund, near-bankrupt, unrepresentative and ill-equipped to enthuse the electorate.’

They know all this, but they have been unable to reckon with it, to turn their parties into expressions, representations, of social sentiment, to inspire people, to articulate with clarity the interests and vision of large swathes of the British populace. Instead, their leaders accelerated the hollowing-out process, jettisoning the baggage of tradition, Clause 4 and all. For New Labour, it was called modernisation; for the Tories, so-called detoxification. For both, it separated the party, indeed liberated it, from what used to be its support base.

And they did something else, too. As the distance between party and people, government and electorate, grew, the political class sequestered itself away from the electorate – in the EU. It made sense, of course. Established in 1992 with the Maastricht Treaty, it was always a post-Cold War, post-ideology institution, a way for post-ideological elites to govern in the absence of the electorate, to make policy from afar, to rule without accountability. This is why so many members of Britain’s political class were pro-EU. It provided a fig-leaf to cover up the crisis of illegitimacy in their parliamentary midst, a way to manage the yawning chasm between politicians and those they represent. In the form of the EU, policy and law could be made without the electorate.

But no more. With the decision to leave the EU, the political class has been left exposed. Policy can no longer be made from afar; and legislation can’t be blamed on supposedly faceless commissioners. That’s what has so spooked MPs, ministers and others in the world of Westminster, what has prompted them, from all sides, to collapse into disarray – because they now have to reckon, honestly and truthfully, with the chasm that divides them from their only real source of support and legitimacy: the people.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist and editor of the spiked review.

Picture by: Getty Images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.