No, Remain has not won the economic argument

It’s simply not proven that Brexit would be bad for the economy.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The most important reason to vote Leave on 23 June is to strike a blow for democracy following years of erosion in political engagement and accountability. This decay in democracy has been a common national trend in Britain, in other EU countries and in many other parts of the advanced industrial world. It is within national territories that elites have spurned accountability to their peoples. While the undermining of democracy is not something that emanates only from Brussels and Strasbourg, the outsourcing of authority and decision-making from European capitals to the unaccountable institutions of the EU is the most important manifestation of this trend.

While national electorates are still usually able to get rid of and replace their own political leaderships – though the EU explicitly denied that democratic right when it imposed technocratic governments in Italy and Greece in 2011, and has compromised it further in making threats against elected governments in Austria, Poland and Hungary – these same national electorates cannot vote out the collective European Council of the heads of the member states that makes most of the big decisions on EU-wide policies.

Leaving the EU is no panacea for restoring democracy; that is an ongoing struggle. But it would strike a powerful blow for regaining the democratic initiative and reviving popular sovereignty. The fact that the EU today is visibly failing and fostering inter-region conflicts and fragmentation only adds urgency to the democratic case for change.

While this political argument will continue right up to polling day, it has been undercut by the widely held notion that the economic case has already been decided: in favour of remaining inside the EU. A vote to leave is believed by people on both sides of the sovereignty debate as being likely to cause recession and huge job losses in the short term, and probably a smaller economy into the future. With just about every leading national and international economic institution – including the International Monetary Fund, the OECD, the UK Treasury and the Bank of England – making this claim, it seems to many a sure consequence of Brexit.

This apparently overwhelming economic case for staying in has got in the way of the popular sovereignty arguments, swaying many democrats and others open to the democratic case for exit to plump instead for remaining. ‘If the economic cost is so certain, better to be safe than sorry.’ These people may be sceptical of the precise economic claims made by the Remain side. Very few would bet on chancellor George Osborne’s forecast that every household will be £4,300 worse off in 2030 outside the EU (a relative outcome that anyway would be impossible to measure). But they are convinced that leaving would be a hit to the British economy.

Most of the prominent Leave campaigners have been far too defensive on these economic claims. It is an unnecessary concession to the Remain side. Economics is not a reason for hesitation in the face of the political arguments. And the economic case for staying actually doesn’t stack up.

That the great and the good from the business and economics world that have lined up for remaining in the EU is entirely what we should expect in today’s conservative times, when change has become a source of great unease. This accord is not evidence of the substance of their claims. There is no conspiracy that unites them all, or makes them sing the Cameron-Osborne tune: as establishment bodies and supporters, they are simply expressing their support for the status quo.

Established businesses too – while often talking the talk about the disruptive benefits of innovation – have in practice not only been reticent disrupters, based on their abysmal record of capital investing, but have also strongly resisted changes that risk disrupting and undermining their own position. Leaving the EU would be a big change – that’s why it is worth fighting for – but change is scary to most incumbent institutions and businesses. Hence, their commitment to Remain.

The economic arguments themselves are fatuous and flimsy. The models they appeal to that project national output to be smaller out than in the EU merely reveal that these academic exercises are internally consistent. The adverse assumptions about the effects of leaving that are put into the models produce negative outputs. How could they yield anything else? Make the presumption that Brexit leads to businesses spending and investing less and the models’ results show… less investment and smaller economies. This is spreadsheet economics, not intellectual acumen.

Mistaken models don’t make reality, which is why their economic forecasts are so often wrong even six months ahead, never mind 15 years away. The tiny number of alternative models that show positive benefits from leaving are no more helpful because they just make the opposite assumptions.

Most models and arguments against exit rely upon the ‘uncertainty effect’. Changing a status quo that we are familiar with is bound to foment uncertainty. Brexit would bring uncertainty about future trading and other relationships between Britain and the EU countries. The reasoning goes: as uncertainty is a bad thing for businesses and households, this greater uncertainty means the economy will suffer.

Leave aside the impossibility of measuring degrees of uncertainty: a common proxy measure is the number of mentions of the word ‘uncertainty’ in the media – a rather circular definition. More importantly, the contemporary economic role assigned to uncertainty is also circular. Since the future is always uncertain, and businesses, households and policymakers are constantly making their decisions in that context, there can be no determinate economic effects of uncertainty. It coexists with times of boom and slump. The Cold War 1950s was perceived to be a very uncertain time – people were continually considering the four-minute warning of nuclear Armageddon – yet it coincided with the buoyant investing and spending of the postwar economic boom.

What today’s obsession with uncertainty tells us is that society has become much more uncomfortable with change. The revulsion with uncertainty is another way of saying: keep things as they are. This is why appraisals of the economic role of uncertainty are convoluted and become so silly. The Bank of England’s Inflation Report in May – another occasion for governor Mark Carney to warn of the dangers of a Brexit – illustrated some of these absurdities in a special section on ‘Uncertainty and GDP growth’.

The box makes the senseless point that a ‘sharp fall in GDP could be associated with uncertainty around the extent to which it will recover’ – apparently the economy is weak because of the uncertainties arising from economic weakness. Then, having asserted that increased Brexit uncertainties are a big problem for the economy, it gets its excuses in early for why a post-referendum Remain result bounce might fail to materialise: ‘The effects of uncertainty on spending may persist for some time even after uncertainty recedes.’

So the supposedly depressing effects of uncertainty can continue after the cause of uncertainty passes. Of course in the next Inflation Report, after such a vote, we can anticipate that other sources of uncertainty will be highlighted to explain continued economic sloth: a US interest rate rise; no US interest rate rise; the Chinese slowdown; a Trump presidency; low oil prices; rising oil prices; whether we’ll see much sun this summer.

The key point that should be made on economics and the referendum is that there can be no compelling economic case for or against the EU because what happens to growth depends primarily on the actions that are, or aren’t, taken, whether inside or outside the Single Market. Britain’s economic future is primarily the outcome of today’s state of fundamentals, and of decisions still to be made, mainly in Britain but also to an extent elsewhere in the world, since those decisions can impact on the global economic context in which Britain operates.

One of the main reasons that leading Leave campaigners have struggled on the economics issue is that they share a great evasion promoted by the Remain camp: the erroneous belief that Britain today is in robust economic shape. The notion that Britain is doing pretty well has gone unchallenged. Again and again it is pointed out that Britain has had the strongest record of economic growth within the major Group of Seven advanced economies in recent years.

But this avoids the more pertinent point that all the advanced economies have had an abysmal recovery since the financial crash. Temporarily Britain has had a few better tailwinds than others, primarily resulting from the positive effects of zero interest rate policies for spending by business, consumers and the British government. It is often forgotten that ‘austerity’ Britain is running a bigger activity-supporting public budget deficit than most other G7, and EU, countries. Super low interest rates have enabled old debts to be serviced easily and new ones to be taken out. This has helped employment growth, which directly boosts national output.

Undermining this apparently benign economic condition, British productivity levels – output per hour: the most important determinant of prosperity – have barely progressed from where they were in early 2008, before the West’s big financial crash. As a result, income levels for low and middling households have stagnated. Employment rates are high but this says nothing about the quality of recent employment gains.

Most of the new jobs created over the past decade are less secure – many rely on continued easy debt funding. They also pay lower incomes than the jobs they are replacing. The consultancy EY ITEM Club explained that the consequence of British workers moving into poorer paying, as well as more part-time work, is that the distribution of wages has shifted downwards, with the number of workers earning over £45,000 having fallen by around one seventh in the post-crash period.

Very little of this sorry economic malaise is the fault of being in the EU. But it refutes the falsehood that continued membership is a passport to economic success. Instead of confronting the fantasy picture of a strong economy that could be buffeted by post-Brexit changes, the official Leave campaign has let itself be diverted into conjecturing about what trading arrangements Britain would substitute for its EU Single Market membership. Would it be something like the current Norwegian, or Swiss, or Canadian, or Turkish arrangements? There are two flaws with going down this path of speculation.

First, the trading deal Britain establishes with the EU27 is one of those future policy actions that cannot be predetermined. It will derive from what is negotiated with the EU, which will represent a compromise that will appear to serve best the different national economic interests involved.

Moreover, the particular trading relationship established with the 27 other EU countries is not the decisive factor for Britain’s economic future. Nor is there some unique perfect alternative to existing Single Market arrangements that would bring about the ‘best’ economic outcome. Each possible British-EU trade arrangement established would not bring about a fixed economic future. Trading deals are only one small component of how the economic future could evolve. When organisations claim that leaving the Single Market will mean so many jobs are lost, that manufacturing will experience such-and-such a contraction, and that wages will fall by so much, what is ignored is that all these things are driven not by trade access but by productivity.

Most countries in the world are not in the EU Single Market. Their economies do well or badly not because of, or despite being outside of, the Single Market, but because of the state of their own fundamentals of investment and productivity, the impact on them of world economic developments, and the national economic policies that they pursue.

Trading arrangements do not ordain Britain’s or any country’s levels of jobs and wages. These are determined by the amount and quality of investment taking place embodying innovative processes, and the resulting level of productivity. Foreign trade is one of the ways nations can realise their economic possibilities, but it doesn’t magic them up in the first place. Models like the UK Treasury one, which claims that it does, falsely turn the genuine correlations existing between trade and growth into trade being a causal driver of growth.

A national economy could negotiate the best tariff-free, barrier-free deal with every other country in the world, but if its productivity was below its competitors’ levels then it would still not be prosperous. Remember that current British membership of the allegedly beneficial Single Market coexists with British productivity being about one-fifth below the average level for the rest of the G7 economies. It goes with Britain running its largest current account deficit with other countries since annual records began in 1948.

A UK trade deal similar to any of the existing ones secured by other countries would have effects that are dependent both on how Britain’s economic fundamentals develop and also on other policy decisions taken. Even the Treasury model, with all its unfavourable trading assumptions, could conjure up an annual difference in economic growth of only a few tenths of a per cent. This would be small change compared to what happens to productivity: will the average rate of productivity growth get back to about the historic two per cent mark, rather than the flatlining experienced over the past decade?

Economically, the UK could crash, or it could thrive – whether inside or outside the EU. What matters are the policies pursued. More of the same will likely mean the continued decay in Britain’s capacity to create new sectors, industries and jobs. On the other hand, a break with the past evasion, in recognition of the urgency of restructuring its misfiring engine of production, could reverse all this. One of the things that leaving the EU on democratic grounds could enable is taking control of working out, implementing and adjusting the alternative economic policies that advance this overdue shake-up.

Phil Mullan is author of The Imaginary Time Bomb: Why an Ageing Population Is Not a Social Problem (IB Tauris, 2000: (buy this book from Amazon (UK) or Amazon (USA)), and Re-Mojo: Putting an End to the Long Economic Depression (forthcoming).

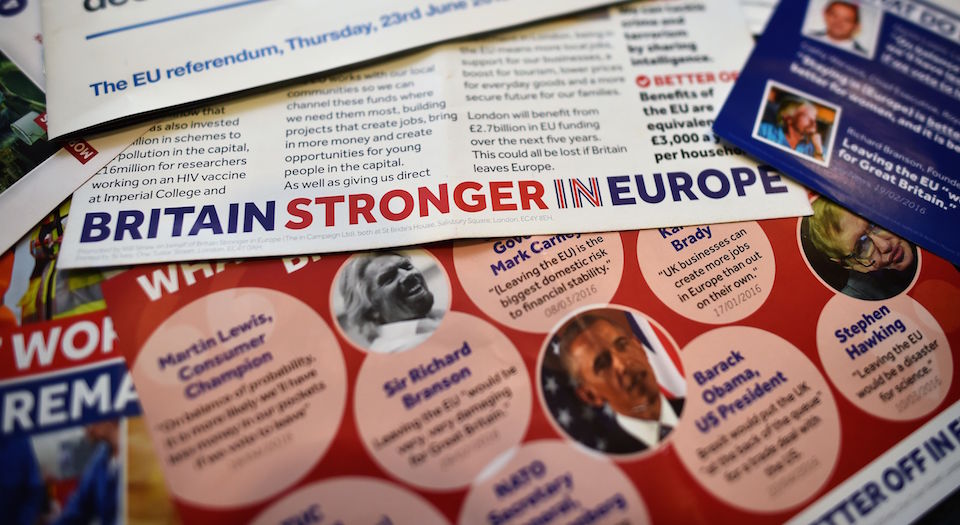

Picture by: Ben Stansall / Getty Images.

Watch spiked’s film, For Europe, Against the EU:

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.