Students are standing up for free speech

Blair Spowart reports on the anti-Prevent protest at the University of Edinburgh.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

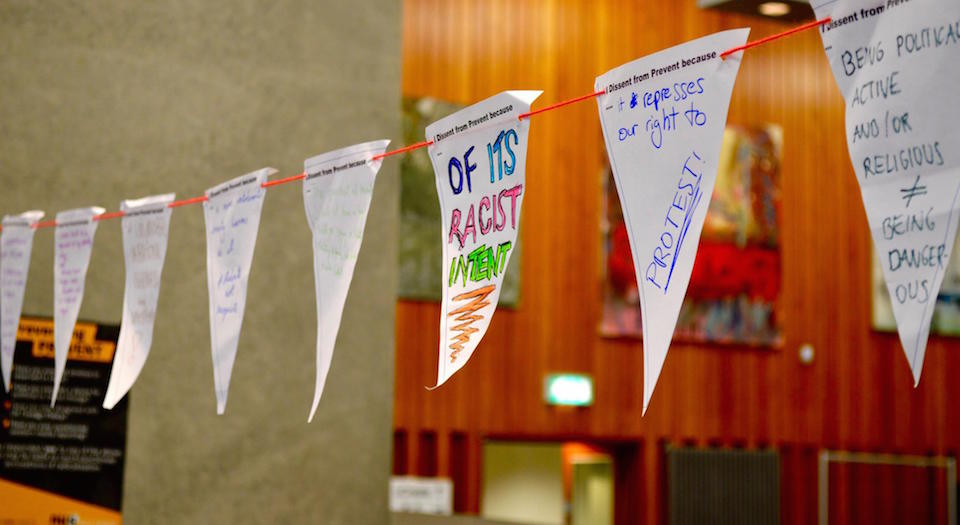

Last week, student protesters at the University of Edinburgh staged an overnight occupation of the university library on George Square, in protest at the UK-wide Prevent anti-radicalisation scheme in higher education. Sleeping rough on the ground floor – amid ‘Students not Suspects’ banners, calling on Edinburgh students to ‘Fight the Prevent Policy’ – the protesters were there to demand that the university, though legally required to implement Prevent, publicly denounce the scheme. Brought in last year as part of UK prime minister David Cameron’s controversial anti-radicalisation strategy, Prevent legislation requires universities to No Platform extremist speakers. Staff are also required to monitor the behaviour of students for signs of what the government calls ‘radicalisation’.

It was encouraging to witness direct student action against one of the biggest current threats to their academic freedom and autonomy. In government literature on Prevent, universities are spoken about in the same vein as prisons – dangerous breeding grounds for extremism whose inhabitants are one hate-fuelled rant away from purchasing a one-way ticket to Syria. The casual lumping together of prisons and places of learning speaks to a complete failure on the part of the government to realise the unique potential of universities to act as spaces where radical, even violent, ideas can be understood and strong counter-narratives produced. Though ostensibly aimed at tackling all forms of extremism, the disproportionate focus on Islamist hate preachers in Prevent betrays an assumption that Muslim students in particular are not up to the challenge of thinking autonomously.

These concerns were writ large in the comments of the protesters last week. Talking to spiked during the protest, one activist admitted that there is a problem with Islamic extremism, and also identified a general, politically correct hesitancy to challenge it: ‘We shouldn’t be so worried about coming across as racist that we fail to the criticise the extreme elements of Islam.’ This is right – if people are too scared of being labelled a racist to challenge a violent ideology, the government will only feel more justified in stepping in. Still, the Prevent policy is actively counterproductive. ‘The government implementing policies that target and monitor the Muslim community on campus is precisely what turns normal students into Islamists’, said one student. Another protester emphasised the unique potential of the university, and the government’s undermining of its function: ‘This is an educational establishment. The university could advertise controversial events and allow students to go along and heckle. But the government should butt out.’

If these arguments sound familiar, it’s because they’re the same arguments that have been on spiked since these protesters were in nappies. Spiked has long resisted attempts by the government and other institutions (including, of course, universities themselves) to restrict what students can hear, think and say, on the basis of two premises. First, that the nature of universities as institutions dedicated to truth requires that any opinion, no matter how extreme, radical or downright mad, can be aired and tested – universities are (or should be) Millian arenas. And second, spiked argues that students are morally autonomous adults. Restrictions on speech, which stop us from discussing or engaging with and criticising whomever and whatever we like on our own terms, are a gross violation of our autonomy. Making these points in the context of Prevent legislation, the protesters generally nodded along.

That was until we moved on to discuss other threats to freedom of speech in the academy. When we discussed No Platform, Safe Space and other student-led attempts to regulate speech, it soon became clear that such arguments against Prevent no longer held much water.

We asked Edinburgh University Students’ Association’s (EUSA) Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) convenor, Shuwanna Aaron, what she thought of the recent, now notorious, Safe Space complaint against a EUSA vice president, who was almost removed from a student council meeting for raising her hand as a sign of exasperation or disagreement. According to Aaron, this complaint was entirely justified: the hand-raising was ‘intimidating’ to other students in the room. What about Edinburgh student and spiked writer Charlie Peters’ petition, calling on EUSA to remove its No Platform and Safe Space policies? ‘I know about that. I hate it. I haven’t read it but I know it’s bad.’

So Islamic extremists shouldn’t be prevented from speaking on campus – but God forbid anyone make an intimidating hand gesture. What happened to treating students like morally autonomous adults? What of the commitment to academic freedom that was so important in combatting Prevent? The truth, of course, is that for many of these protesters, talk of freedom of speech and intellectual autonomy is just opportunistic guff. In this particular case, they’ve found it convenient to feign support for free speech because it happens to suit their aims. But when their own desire to police and regulate the language of students comes into question, their backing for intellectual autonomy is nowhere to be seen. The reason for this is obvious. Their only real commitment is to their own narrow brand of identity politics – and if this means a short-term, disingenuous concern for freedom of speech, then so be it.

This failure on the part of student activists to defend freedom of speech in a principled way is precisely what gave the government the green light to implement the Prevent scheme in the first place. The NUS and its affiliated unions, having spent most of their time worrying about banishing whatever offends their Victorian sensibilities from campus, can hardly complain when the government takes advantage of that censorious climate. Moreover, as much as the NUS now loves to imagine itself as defender of put-upon Muslim students against a censorious government, it already had No Platform policies against Islamist groups such as Hizb-ut-Tahrir in place since 2006 – years before the Prevent scheme was implemented. Indeed, the government report on Prevent actually praises the NUS for its ‘positive actions towards tackling extremism’, describing its No Platform policies as ‘largely effective’. Some anti-establishment radicals, eh?

That all said, the Prevent protest did offer some grounds for positivity. Some of the protesters spiked spoke to were clearly grappling with these very questions and contradictions – torn between their commitment to university-style identity politics on one hand, and the value of a robust, daring, no-holds-barred academy on the other. When we asked one protester what she thought of the recent petition to ban Germaine Greer from Cardiff University for her comments on transgenderism, she said: ‘I disagree with the idea of people being banned. People need to hear what they have to say.’ But shortly afterwards, she added: ‘This whole debate – I find it difficult. It’s always the people who’ve had the opportunity and the privilege to speak who question censorship of speech which is really, really offensive to marginalised groups.’ ‘Isn’t this the same logic that the government uses to implement Prevent?’, we asked. ‘Yeah, I know. That’s why I find it really difficult.’

There is a tendency among those who support free speech in debates on campus censorship to characterise those who want to regulate speech as committed authoritarians. There is a corresponding tendency for the supporters of regulation to characterise those who believe in free speech as utterly unmoved by appeals to equality. In fact, as the exchange with this protester suggests, the picture is usually more mixed. Yes, those at the extremes – like the BME convenor – are probably lost causes, indulging in authoritarian excesses without a second thought. But most people, on both sides of the debate, see value in both autonomy and equality – they just think that one outweighs the other. The importance of unfettered debate on campus has really hit home – even if not enough students have yet been convinced that those arguments outweigh concerns about equality.

Our challenge, then, is not so much to convince the rest of the student body that our ability to engage with and criticise others on our own terms, without government or NUS/SU interference, is important for the academy and for our own intellectual autonomy. Most students now seem to accept that, at least some of the time. Rather, it’s to convince students that this is what’s most important – or too important to be sacrificed at the altar of identity politics. So, yes, some of the protesters displayed a frustrating hypocrisy. But spiked’s efforts have in many ways been vindicated – and that’s reason to be hopeful.

Blair Spowart is a writer and a student at the University of Edinburgh. Follow him on Twitter: @blairspowart

Pictures by: Thurston Smalley, President of The Student, the University of Edinburgh’s student newspaper.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.