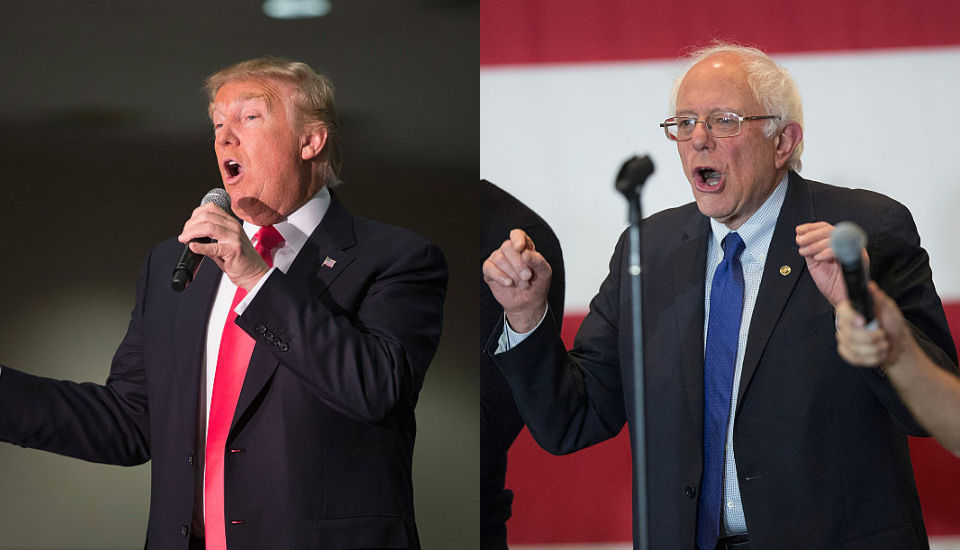

Is the game rigged against Trump and Sanders?

No, these outsiders aren’t being done in by their parties.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In this year’s presidential election, the rise of two outsiders, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, has upset the wishes of the Republican and Democratic party elites. Now, as these two have become serious contenders, their supporters are increasingly complaining that the elites have rigged the nomination process against them.

Sanders supporters protest that the Democratic Party’s ‘super-delegates’ are undemocratic and tilt the nomination towards Hillary Clinton. While party primaries and caucuses elect regular delegates, the super-delegates are party bigwigs (governors, members of congress, officials) who also have votes at the nominating convention. The 712 super-delegates make up 30 per cent of the total delegates needed to win the nomination, and thus could sway the outcome – even overturning the popular vote, in theory (that has not happened in practice).

Super-delegates have, so far, tipped the scales in Clinton’s favor. For example, Sanders won the New Hampshire primary by 20 percentage points, but when the super-delegates who plumped for Clinton are included, both candidates earned the same number of delegates. As a New York Times piece argued: ‘You could make the case that the Democratic Party is being downright undemocratic, the superdelegates merely replacing the smoke-filled rooms of the past.’ A MoveOn.org petition against super-delegates states: ‘This process is undemocratic and fundamentally unfair to Democratic primary voters…. Democracy only works when the votes of the people — not the decision of a small number of elites — are what determines the outcome of elections.’

On the Republican side, Trump supporters also believe they are being screwed over by the party establishment, but in a different way. After Tuesday’s primary in Wisconsin, it is looking more likely that Trump may not reach a majority of delegates to secure the nomination before the Republican convention in July. In that case, Trump might fail to gain the nomination, even though he would have the most votes of all of the remaining candidates. This is a real possibility, as the rules allow most delegates a free vote after the first or second round, and the word is that many of these delegates, who are longstanding party members, are not pro-Trump.

Trump himself has warned the Republican establishment of dire consequences if he is denied the nomination: ‘I think you’d have riots. I’m representing a tremendous many, many millions of people.’ His people are increasingly talking of the establishment ‘stealing’ the nomination from him. In a statement after the Wisconsin primary, his campaign said that his opponent, Ted Cruz, ‘is a Trojan horse, being used by the party bosses attempting to steal the nomination from Mr Trump’.

Today’s presidential nominations are more open than those of the past. With primaries and caucuses, millions of voters have their say, and the nominee is no longer handpicked by a smoke-filled room of party leaders. But supporters of Sanders and Trump have a point: the processes within the Democratic and Republican parties are not forms of direct democracy; they are not ‘one person, one vote’. Reforms of the nomination systems – many introduced in the 1970s, in both parties – allowed more popular influence over the outcome and loosened the grip of party leaders, but not entirely. As the authors of the much-cited The Party Decides (2008) noted, ‘In the past quarter century, the Democratic and Republican parties have always influenced and often controlled the choice of their presidential nominees’.

But are the current party processes ‘unfair’, as supporters of Sanders and Trump contend? No. Direct democracy is rightly considered a good thing when it comes to the elections between parties (and the US presidential system could go further in that direction, by eliminating the electoral college). But, within a party, there is no reason why decision-making has to take the form of ‘one person, one vote’. In fact, in a situation where non-party members can vote (as is the case in many primaries), and there are no political standards for determining who can represent the party in elections, direct democracy could have negative consequences, even to the point of eventually undermining the party’s reason for existing. Indeed, you could make a case that the major US parties have become too loose and open, mainly reflecting their inability to state clearly what they stand for.

By historical American standards (and international standards), it is remarkable that Sanders and Trump can so easily vie for the top role within their parties, given that neither were party members before running. Sanders, a senator from Vermont, has spent his decades in politics prominently refusing to join the Democratic Party and denouncing the party as ‘ideologically bankrupt’. After declaring himself a candidate for president, he told an interviewer that he became a Democrat in order to receive additional media coverage – hardly an endorsement of the party’s principles. Donna Brazile, a leading Democratic Party official, called Sanders’ statement ‘extremely disgraceful’, but her party had no way of stopping him.

It is a similar story with Trump and the Republicans. Trump was a registered Democrat in the past, and donated to Democratic Party candidates as recently as 2012. While campaigning, he has regularly raised points and proposals that have been more associated with Democrats, including support for national healthcare, praising Planned Parenthood, and criticising George W Bush for the Iraq War. Republican politicians and conservative ideologues cried foul, but it was not like there was a set of established party principles they could say disqualified Trump.

Now at the receiving end of complaints that the game is rigged, the establishments of both parties have only themselves to blame. For too long, the party bigwigs have been happy to give the impression that their organisations are pure democracies, and that the voters decide everything. But, as this is not the case in reality, giving such an impression only causes confusion, and creates understandable dismay when the process is revealed to be less than ‘one person, one vote’.

Primaries were introduced in the US to obtain input from party members and gauge the political appeal of candidates, but through the mediation of delegates, who make the ultimate decisions. They were never designed to elect nominees directly. Parties are institutions dedicated to the pursuit of specific political interests, and they ought to be transparent that their methods and decision-making processes are subject to achieving those ends.

There are plenty of good political arguments that can be levelled against the standard-bearers of the Democratic and Republican parties, including that neither has represented the interests of the working class. A supposed lack of internal democracy is not one of them.

Sean Collins is a writer based in New York. Visit his blog, The American Situation.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.