Why rape defendants shouldn’t be anonymous

Granting anonymity to men charged with rape will damage the justice system.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

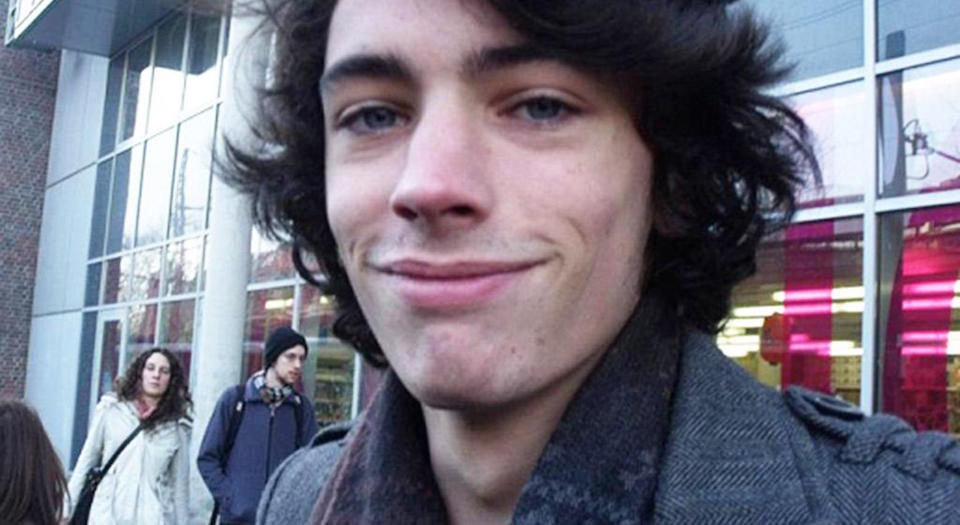

Last week, a young British man was acquitted of rape. Louis Richardson is an ex-member of the Durham University Debating Society. He was accused of attacking a young woman while she was drunk. He was also accused of sexually assaulting another woman at a party. The jury acquitted Richardson of all charges after a six-week trial and a 15-month period on bail. Richardson’s family described how the very public manner of the prosecution made their life a ‘living hell’.

The case has reignited an old debate about anonymity for defendants in rape cases. The argument seems to have a basic pragmatic appeal: the impact of a rape allegation can be so catastrophic for a person’s reputation that the only way to mitigate this impact is to make the proceedings more secretive. Rape claimants enjoy anonymity, people say, so why shouldn’t defendants?

The idea of anonymity is appealing to the world of legal commentary, which has become increasingly obsessed with pragmatism. Lawyers are so desperate to come up with a solution that ‘works’ that they often lose sight of the vital principles at play. Some have argued that anonymity should extend only until a defendant is charged, which would mean a Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) lawyer would have to decide that there was enough evidence to prosecute, and that a prosecution was in the public interest, before the defendant’s identity could be revealed. Others have argued that anonymity should extend throughout the entire trial. Some say anonymity could be removed during the trial if there were apparent benefits in making the identity of the defendant known.

The pragmatic short-sightedness of these responses is remarkable. First and foremost, it is important to recognise that the reason such calls for anonymity are being made in the first place is that the presumption of innocence, a vital principle of our justice system, is now held in very low regard. Today, the fact of an allegation can have a devastating effect on people’s reputations precisely because we fail to distinguish between an allegation and a proven fact. Richardson is hardly the first person to have his life put on hold by an allegation like this. Cases like Ben Sullivan’s – who faced international pressure to stand down as head of the Oxford Union when he faced a rape allegation in 2014 – show how the presumption of innocence is consistently undermined, even where no prosecution is ever brought.

The presumption of innocence is routinely abandoned in modern-day Twitter trials, too, like that of Bill Cosby and photographer Terry Richardson, in which defendants are ‘outed’ by social media and then judged by the court of public opinion. The police and the CPS routinely elide ‘complainants’ and ‘victims’. Their language is illustrative of their approach to cases involving sexual offending, in which defendants are often assumed to be guilty based on allegation alone.

Some say defendant anonymity would help to support the presumption of innocence. Actually, it would do the opposite. Consider the idea that defendant anonymity should remain until a defendant is charged. This proposal raises a question: why should a decision to charge someone mean that their rights as a citizen change? A defendant after charge is just as innocent as a defendant prior to charge. By allowing anonymity only until charge, we would reinforce the idea that being charged somehow makes you less innocent than before. This doesn’t support the presumption of innocence; it undermines it.

Similarly, defendant anonymity throughout a trial would be a disastrous pragmatic solution to the problems in the discussion around rape and sexual violence today. The key aim of reform in this area should be to improve the rate of cases that reach a courtroom and which end in a conviction. This is known as the conviction rate. It’s an important number. It shows the rate by which the CPS and the police are making decisions which cohere with the judgement of the public, as embodied in the jury. A high conviction rate means that the jury is agreeing more often with the state’s application of the law.

Over the past three years, the conviction rate in rape cases has started to fall, from its historic high of 63 per cent in 2013 to 56.9 per cent in 2014-2015. This is the lowest it has been since 2006 (though it is relatively high overall). In order to improve the conviction rate, two things need to happen: first, the police need to be better at investigating allegations. And secondly, the CPS needs to be better at deciding which cases should be charged. Only then will we see an improvement in the ratio between cases charged and eventual convictions.

Interestingly, the fall in the conviction rate has coincided with an increase in the number of people prosecuted for rape. In 2014-2015, 3,648 defendants were charged with rape – that amounted to 59.2 per cent of the cases referred to the CPS by the police. This represented the most people charged with rape in a single year ever.

So today, the CPS is charging more cases but getting a lower ratio of convictions overall. Anonymity would compound this problem, by further removing the decision-making around these prosecutions from public scrutiny. There would be a clear temptation on the part of both the CPS and the police to continue to charge more and more cases on weaker evidence, in the knowledge that their cases would be played out away from the public gaze. The prosecutorial authorities need to know that their decisions will be scrutinised.

Anonymity merely creates a climate in which the CPS is better able to charge more people in the hope of improving the conviction rate. Anonymity will not prevent the disastrous impact that such an approach to prosecuting these cases can have on the lives of both defendants and complainants.

Defendant anonymity is a terrible idea in whatever form it takes. It is only being seriously thought about because of a cultural abandonment of the presumption of innocence around rape. It is foolish, and dangerous, to think that the problems arising from our abandonment of that enlightened principle can be solved by sacrificing universal ideals of justice for some pragmatic tweaks to the system.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practising criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. He is the author of Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.