When Bowie was not a ‘national treasure’

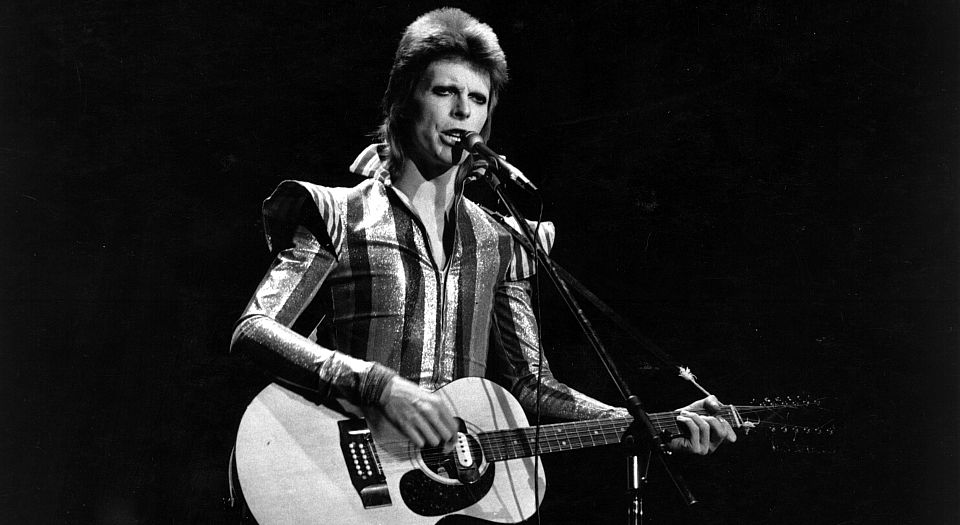

The Seventies starman was the spirit of that turbulent age in dayglow jumpsuit.

In death, it appears, David Bowie has been turned into an anodyne ‘national treasure’, as if he were the Princess Diana or even the Queen Mother of pop music. Everybody in public life, from Tory prime minister David Cameron and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn to the Archbishop of Canterbury and even the Vatican’s ‘chief spokesman on cultural matters’, felt moved/obliged to issue mournfully adulatory statements following the shock news of Bowie’s death aged 69.

Cameron might well have been right to say that ‘musically, creatively, artistically, David Bowie was a genius’. Yet he was not always the type of genius to have his talents recognised by prime ministers and papal spokesmen. (Nor, to judge by his laudable refusal to take part in the circus-like opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics, does he seem to have aspired to national-treasure status.)

In the early Seventies, Bowie emerged as the spirit of that rebellious age in a dayglow jumpsuit. His theatrical flirtations with everything from bisexuality to fascism ruffled feathers. Most importantly, however, the music he made in those few years captured the creative energy that gives the lie to the prejudice that the Seventies was a grim, grey decade.

Many of us entering adolescence in the early Seventies were ready for something new that was neither bubblegum pop nor stodgy, indigestible prog rock. When my eldest sister came back to our family home from a summer job waitressing on the south coast, she brought two new albums by an artist she had seen perform and met down there. They were Bowie’s two classics-in-waiting – Hunky Dory and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. In sleepy, suburban Surrey, we had never seen or heard anything like it – apart from the brief glimpse of the future we had just had in his path-breakingly camp performance of ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops in July 1972.

Bowie had essentially been a 1960s mod; in 1964, the 17-year old David Jones appeared on BBC TV’s serious Tonight programme as founder of The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men, which some might think put him in the vanguard of victim, as well as pop, culture. His musical tastes from those days were reflected in the last of his albums I bought, Pin Ups, the 1973 collection of Sixties covers that includes a version of Ray Davies’ ‘Where Have All the Good Times Gone’, which, were it not sacrilege, I might even suggest is as good as the Kinks’ own.

Even then, however, Bowie was ahead of the curve. My friend Ed Barrett, writer and self-confessed ‘Bowie nerd’, relates how his manager gave Bowie an acetate of the Velvet Underground’s first album in late 1966. By the time it was released the following year, Bowie was already doing a version of ‘I’m Waiting for the Man’ with a band called the Riot Squad. ‘This album was later claimed as an influence by hundreds of musicians’, says Barrett, ‘but at the time it sold badly and was unknown to most people. Bowie did various covers of it over the years and recorded the tribute ‘Queen Bitch’ on Hunky Dory, which name-checks the Velvet Underground on the sleeve. It’s an example of how he picked up on things early and commercialised them brilliantly.’ Bowie also gave as good as he took, helping to produce and popularise his influences and favourites such as Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, Mott the Hoople and Roxy Music. He even gave Lulu a leg-up.

The early Bowie sound of the Seventies was in no small measure down to Mick Ronson, the star guitarist and arranger who was rescued from musical retirement as a parkie in his native Hull to come back down to London and lead Bowie’s band, becoming the real-life chief Spider from Mars. Ronson, who famously and flirtatiously dueted with Bowie doing ‘Starman’ on TOTP, died back in 1993 without the sort of plaudits he richly deserved.

Those defining three Bowie-Ronson albums of the early Seventies – Hunky Dory (probably the best), Ziggy and Aladdin Sane – stand out in my memory as the long-playing soundtrack of those turbulent years, alongside Slade’s riotous Slayed?. I recall being had up by a teacher for singing pop songs rather than the set hymns during a music lesson, at the back of a prefab classroom circa 1974. ‘But sir’, objected my co-accused as if it were an unanswerable defence, ‘it’s David Bowie, sir!’.

By the time Bowie had got through his drugged-out years to produce the Berlin albums that all the music critics have been raving about this week, my friends and I had largely given up on his new music. Bowie said later that the 1980 single, ‘Ashes to Ashes’, with its ‘iconic’ video of him dressed as a clown with the Blitz-scene new romantics, was ‘wrapping up the Seventies, really’, which ‘seemed a good enough epitaph for it’. That also marked the end of Bowie for me, although his major commercial successes came later. If, as John Lennon said on hearing of Elvis Presley’s death in 1977, ‘Elvis died when he went in the army’ (in 1958), then, for some of us at least, Bowie the musical genius passed over when he appeared in that Pierrot costume alongside Steve Strange and Co.

The starman of the early Seventies, however, still shines as the great taboo-busting British artist of the pre-punk era. There has been a lot of things said this week about how Bowie changed people’s lives, made them what they are, even changed British attitudes to sexuality and gender, etc. His androgynous characters and performances surely caused a lot of jaws to drop and eyes to open (though Bowie would later say that he was ‘always a closet heterosexual’).

Yet, as always, the attempt to depict an artist or a sportsman as a ‘role model’ changing the world is fraught with problems. Would anybody now suggest, for example, that Bowie also made fascism fashionable with his infamous statement, amid the political turmoil of 1974, that ‘Britain could benefit from a fascist leader… I believe very strongly in fascism, people have always responded with greater efficiency under a regimental leadership’. If any musician came out with similar today, many of those who have been beatifying Bowie on social media would surely be signing online petitions for them to be banned, if not arrested.

To get a true sense of Bowie’s appeal and influence in his early Seventies golden years, look at this film taken during his Ziggy Stardust tour concert at north London’s Rainbow Theatre (deceased) in August 1972. The video contains an interview with two long-haired working-class blokes, done up to the nines for the gig in cosmetics borrowed from their girlfriends. Bowie, says one, had made make-up ‘a fashion thing. You don’t have to be bent to wear make-up. Now you can put it on without people saying too much.’ Elsewhere, another young man from the terraces raves about Bowie, while admitting that he’s ‘never raved about anybody in my life’, because ‘this bloke’s got something that nobody else has got’. And if anybody disagrees, he only half-jokes, ‘I’ll punch his head in’. All a far cry from the later arthouse Bowie followers who have tended to monopolise the discussion after his death. During the Earl’s Court gig on his 1976 Thin White Duke tour, the Buñuel film Un Chien Andalou, rather pretentiously shown on a big screen before the concert, was pelted with beer glasses by impatient fans chanting ‘Bowie! Bowie!’ football-style.

Last word to Elton John, now perhaps the true Queen Mum of pop music, but who appears in that concert film as a young pop star and Bowie fan. Asked what he likes about the Bowie of ‘72, Elton replies that ‘Above all, apart from all the glamorous rubbish and all that, the music’s there’. So it was, and always will be.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by Harper Collins. (Order this book from Amazon(USA) and Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.