Cosby showtrial: is the accuser holy now?

The whispers about Cosby have chilling echoes of Salem.

Arthur Miller’s seminal play, The Crucible, tells the story of the small town of Salem, Massachusetts, which in the late 17th century became caught up in allegations that various townsfolk were engaged in witchcraft. The play offers an analogy of the McCarthyite trials of communists during the Fifties, which were famed for abandoning due process in the name of rooting out and punishing accused radicals at all costs.

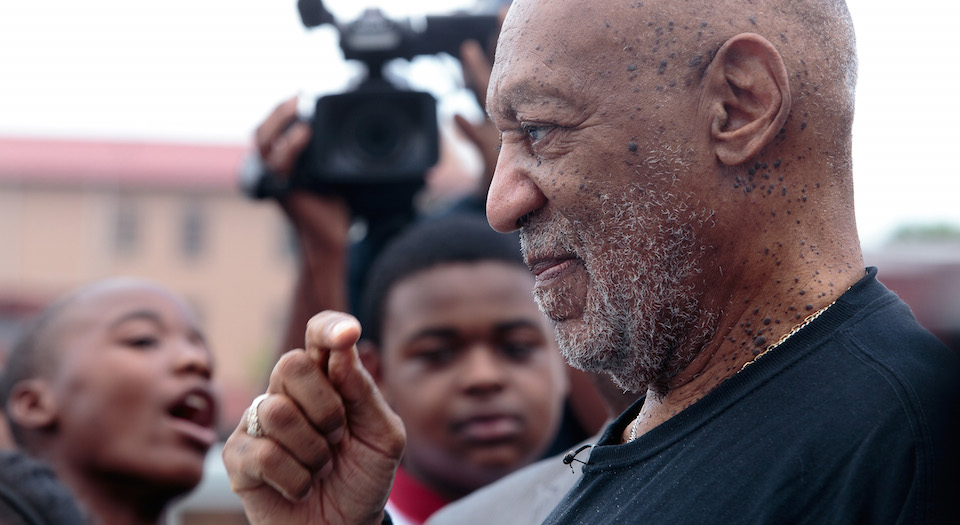

The play has become the go-to cultural reference for illustrating the dangers of pursuing mob justice in a time of hysteria – and for good reason. In the first act of the play, after his wife is accused of witchcraft and bundled away on shaky evidence, the protagonist John Proctor proclaims, ‘Is the accuser holy now?’. Proctor’s line points to the danger of unquestioningly accepting the narrative of accusers and abandoning any obligation to establish the truth. Today, after the surreal chain of events that has led to the prosecution of comedian Bill Cosby, Proctor’s words still have a haunting ring.

Cosby has been charged – or ‘finally charged’, in the words of his many detractors – with sexual assault against former basketball player Andrea Constand. In the lead-up to what is the first step of criminal proceedings, events have unfurled in the most public, persecutory way possible. In fact, Cosby’s case would not have been pursued had it not been for internet comedy. In October 2014, a YouTube clip emerged showing comedian Hannibal Buress publicly, and rather casually, accusing Cosby of rape during a stand-up routine. This rape joke – the kind of rape joke that is apparently okay because it makes light of rape for some kind of greater good – was the catalyst for the proceedings against Cosby. Since the clip emerged, more and more women have come forward to accuse Cosby of sexual assault. While most of these cases are barred from prosecution because of statutes of limitation, Cosby nonetheless faces eight civil lawsuits, along with criminal proceedings.

At the end of The Crucible, Proctor pleads with the prosecutors: ‘How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name.’ Today, in the era of the Twitter trial, a person’s name is often the first thing to be sullied. Cosby’s reputation was irreversibly tarnished before any evidence was even considered. Various institutions have revoked honorary degrees awarded to him, and TV networks have ditched reruns of his programmes. Whatever the outcome of the prosecution, Cosby has lost his name forever.

What Cosby’s case has in common with the witch trials of old is the same quest for simple narratives and swift justice. In Miller’s play, the inhabitants of Salem seek to shame their subjects instead of investigating them. The truth of what is alleged is proven by the act of making the allegation itself. Both Cosby’s accusers and the religious zealots of Salem are willing to use a showtrial to denounce and deliver retribution, rather than take the time to investigate the evidence.

The effect of this rush to judgement is compounded by the complexity of the Cosby case. The truth of the allegations against him is far from clear. In 2004, Constand accused Cosby of drugging and fondling her. She claimed that Cosby had been a ‘mentor’ to her and that she had attended his property on numerous occasions. On two of these occasions, she claims, Cosby urged her to drink wine and take pills until she was unable to move. Cosby then sexually assaulted her. Unusually, Constand accepts that after these two alleged assaults she returned to Cosby’s address on a friendly basis, a fact that his lawyers have pointed to as ‘significant’.

The district attorney at the time decided not to pursue any criminal case, on the basis that there was no credible material upon which to found a prosecution. Constand brought a civil case against Cosby, which he settled in November 2006. The evidence that Cosby supplied in these civil proceedings has now been unsealed by those investigating the criminal case. In that evidence, Cosby conceded to ‘offering women Quaaludes’ prior to sexual acts. He maintains that this was consensual and that Quaaludes (strong sedatives) were not nearly as unusual in the past as they are now.

In other words, Cosby’s alleged behaviour was odd, especially by today’s standards. But whether his actions were criminal is a very complex question, which demands the consideration of the actual evidence against him.

The decision to prosecute Cosby is further complicated by the process of selecting prosecuting lawyers in the US. In the US, district attorneys are elected. The original attorney who decided against prosecuting Cosby was replaced by a new incumbent who had campaigned on the basis that he would prosecute Cosby. In an interview with CBS, Cosby’s lawyer argued that the district attorney prosecuting Cosby was ‘hungry’ and keen to ‘follow up on a campaign promise’. In Cosby’s case, evidence that was first deemed to be unreliable has been rendered more credible by a different lawyer, in light of new evidence that has emerged since the primary evidence was first considered. In other words, the key evidence has been deemed more reliable based on Cosby’s own concessions and the allegations of other women. While there is likely to be significant disagreement as to whether the new allegations should go before a jury, the protracted media showtrial against Cosby means it will be hard to find any juror who does not know about the new allegations.

Cosby’s accusers may not be considered ‘holy’, as the accusers of Salem were, but they have certainly become celebrities who have been celebrated merely for making their voices heard. Last year, in a move that brought the case to a nauseating new low, those accusing Cosby took part in a cover shoot for New York magazine, appearing under the title ‘Cosby: The Women’. While the decision to make a complaint against someone in the public eye does take courage, the decision of New York magazine to parade these women before the world as heroes, before any formal consideration of their claims, showed how sections of the media have taken leave of their senses when dealing with the Cosby case.

Last week, another New York newspaper featured a picture of Cosby’s mugshot on its frontpage with the words ‘he said she said’, with ‘she said’ repeatedly cascading down the page. The message of the headline had haunting commonalities with the religious proclamations of the Salem witch trials: if this many people say something, then what they say must be true. The same paper had previously featured a picture of Cosby with the words ‘America’s Rapist’.

What we stand to lose in this new climate of ‘no smoke without fire’ justice is the acknowledgement that the truth is often complex. For the most part, the kind of behaviour Cosby is accused of is open to different interpretations. Perhaps Cosby did drug these women against their will and then fondle them while they were unconscious. But we have to find this out in the proper way. If we don’t, we have no chance of moving beyond the wild hysteria that (spoiler alert) ruined the town of Salem.

When discussing his play, Miller said ‘it is rare for people to be asked the question which puts them squarely in front of themselves’. Today, the question of how we deal with allegations of serious sexual violence is one that we as a society are woefully failing to answer in any rational way.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practising criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. He is the author of Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Picture by: David A. Smith / Getty Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.