Fuck tha thoughtpolice

More than 25 years after NWA rocked the world, rappers are still being muzzled.

Straight Outta Compton, the new blockbuster biopic of NWA, is everything it should be. It’s a fire-spitting thrill-ride, charting the South Central LA crew’s journey from beaten-down teens, harassed by the police and surrounded by violence, to chart-topping legends – with all the parties, feuds and bloodshed in between. It’s a glossy, (far from) warts-and-all romp with all the expositional rock biopic trappings. But it’s a victory lap that’s well earned.

Today, now that gangsta rap sells to tween audiences, it’s easy to underestimate just how much of an impact the self-touting Niggaz With Attitude made when they burst on to the scene in the late Eighties. As F Gary Gray’s film shows, when half-pint Compton gangster Eric ‘Eazy-E’ Wright (Jason Mitchell) decided to plough his ill-gotten gains into a record label, and hooked up with DJ Yella (Neil Brown Jr), Dr Dre (Corey Hawkins), Ice Cube (Cube’s dead-spit son O’Shea Jackson Jr) and MC Ren (Aldis Hodge), it wasn’t just the authorities who weren’t ready for their fiery brand of ‘reality rap’.

In late Eighties, the East Coast ruled the airwaves. The sound was jazzy, upbeat, danceable and ‘positive’. The Fresh Prince and DJ Jazzy Jeff – the so-called Cosby kids of rap – topped the charts. The Afrocentric New York Native Tongues Posse launched on to the scene in dashikis. While Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back was a rude awakening, telling tales of police brutality and urban decay, it was fuelled by pious outrage. Straight Outta Compton, NWA’s legendary full-length debut, struck a far more nihilistic tone.

NWA didn’t comment, soberly, on gang life in their music – they embraced it and caricatured it with a no-fucks-given rebelliousness. On the title track, with sirens, snares and horns blaring, we’re introduced to ‘a crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube’ and Eazy-E, ‘the brother who will smother your mother’. It was a visceral, violent and chaotic mission statement, and it had everyone worried. In one hilarious scene in Gray’s film, a local Compton club owner – dressed like Eddie Murphy’s ‘Sexual Chocolate’ – lambasts resident dj Dre for getting Ice Cube on stage to perform ‘Gangsta, Gangsta’. ‘You trying to start a riot?’, he says, before sticking the slow jamz back on.

But it was NWA’s battles with the authorities that made them legends. After years of being pushed around, at the height of the LAPD crackdown on gangs that would later foment the LA Riots, Ice Cube penned the brashest protest song ever written, ‘Fuck tha Police’. The sentiment, muttered by many a black youth as they walked away from a cop car, was suddenly broadcast to the masses. ‘Anarchy in the UK’ looked cute by comparison. The FBI sent Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records a letter warning them not to perform the song, saying it encouraged ‘violence against and disrespect for the law enforcement officer’.

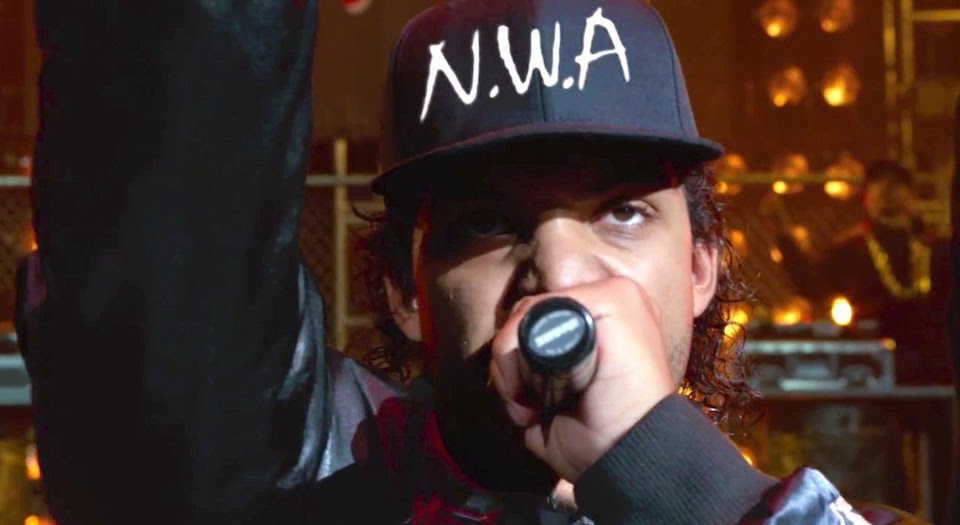

This was only the start of NWA’s brushes with the police. When they went on tour, police refused to police crowds outside the arenas, making wary venues think twice. It all came to a head at a show in Detroit, recreated to air-punching aplomb in Gray’s film. The cops show up before the show, warning that they’ll shut it down if they played ‘Eff the police’. Of course, Cube and Co can’t resist. ‘Yo Dre, I got something to say’, says Cube, before launching into his verse. The police rush the stage and cuff the lot of them. As they’re thrown into the back of the meat wagon, they all burst out laughing. They’d just got the best publicity anyone could dream of.

Today, it’s easy for people to celebrate NWA. At the end of the screening I was in, everyone applauded. But what this misses is that the battle against censorship is still going on – only it’s no longer the police who are telling foul-mouthed rappers what they can and can’t say. In May, Queens rapper Action Bronson was bumped from his main stage slot at Toronto’s NXNE festival after feminists claimed ‘the content of his music glorifies raping and murdering women’. In June, Tyler, The Creator pulled out of an Australian tour after feminist group Collective Shout tried to get the authorities to revoke his visa. And only last week the Home Office banned Tyler from entering the UK for three to five years, in a move many interpreted as a feminist-friendly PR stunt.

Even NWA have not been immune to the new, right-on culture police. In an interview in Rolling Stone last month, Ice Cube caused outrage when he brushed off criticism of NWA’s liberal use of ‘ho’ and ‘bitch’. ‘If you’re not a ho or a bitch, don’t be jumping to the defence of these despicable females’, he said, drawing a fine distinction few took kindly to. Reviews have also bristled at the alleged anti-Semitism and homophobia of Ice Cube’s infamous 1991 diss track ‘No Vaseline’. Recreated in a hilarious sequence in the film, Cube, having left the group after squabbles over cash, takes aim at the band’s Jewish manager Jerry Heller. What’s more, Gray has been accused of smoothing over the darker chapters of Dre’s past – specifically the time he beat up journalist Dee Barnes at an album-launch party in 1990. This omission, many have claimed, gets to the heart of the vicious misogyny that NWA devotees are all too willing to overlook.

Unless you believe that NWA’s violent lyrics spilled over into real life, then whether or not Gray gave Dre an easy ride is a separate issue. Incidentally, he claims the scene was cut for the sake of run-time – and it’s hardly the first biopic that’s chosen to leave out some darker chapters of the story. But the fact NWA can now be hailed for offending the authorities, but slammed for upsetting feminists, shows that the fight for free expression is far from over. What made NWA so powerful was not just that they took aim at the right targets — it was that they said what they wanted. Sure, the stories of ghetto courtship were hardly Jane Austen, but, in the fiery, chaotic, no-holds-barred world of their music, it was thrilling. And, in the time of Tipper Gore’s prudish Parents’ Music Research Centre – for whom we have to thank for those nifty ‘Parental Advisory’ stickers – it was much needed.

That the Niggaz With Attitude are still causing outrage three decades later proves there is plenty left to fight for.

Tom Slater is assistant editor at spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Watch the trailer for Straight Outta Compton:

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.