The EU is digging Orwell’s ‘memory holes’ across the internet

The ‘right to be forgotten’ is a threat not to Google but to free speech.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

To all of Google’s glowing self-descriptions, it appears we must add another: Google as global fighter for freedom of expression and information. The internet giant has just made headlines around the world by rejecting a demand from the French data protection authority to extend the EU-backed ‘right to be forgotten’ across all of its platforms. This would mean, for example, that if the company granted a request to remove a link from google.fr or google.co.uk, it would automatically be obliged to remove the same link from google.com.

In response to the French demand, backed by threats of repeated fines, Google declared that, ‘as a matter of principle, we respectfully disagree with the idea that a national data protection authority can assert global authority to control the content that people can access around the world’.

You need not search very hard to find that, ‘respectfully’, the search engine’s bold words are empty google-degook. Anti-corporate critics have pointed out that Google itself seems to have few qualms about controlling what information people are permitted to publish online. More pertinently, Google has done all in its power to enforce the EU’s ‘right to be forgotten’ rules within European states, apparently striving to live up to Jeffrey Rosen’s warning when the rules were first proposed in 2012 that the company risked becoming ‘censor-in-chief for the European Union’.

Google’s ‘defiant’ response to the French authorities’ latest demand even began by pleading that ‘we’ve worked hard to implement the right to be forgotten ruling thoughtfully and comprehensively in Europe, and we’ll continue to do so’. Some defiance. The latest recorded figures show Google had received 290,353 requests to remove web links under the 2014 ‘right to be forgotten’ rules, covering more than one million web pages, and agreed to remove some 41 per cent of them. Google might have made a token PR stand against the internationalisation of the right to be forgotten, but it seems happy to support a form of ‘censorship in one country’.

Of course, for all its hipster-style pretensions, Google remains just a corporation, not a political campaign, and nobody should rely on it to fight their battles. Behind the posturing there is a need to remind the world that the EU’s right to be forgotten rules pose a real threat to freedom of expression for us all within every state, and reinforce a wider culture of conformism and safety-first creeping across the internet.

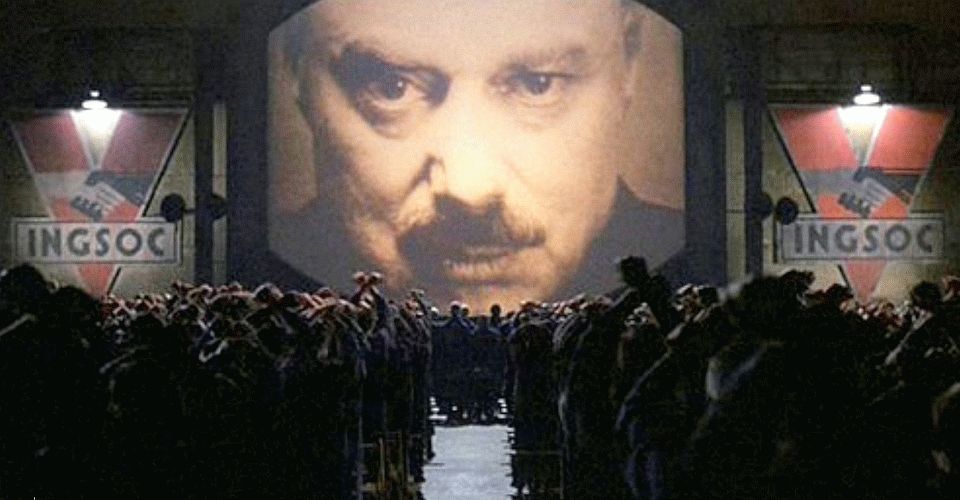

As my book Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech? observes, ‘The concept of “Memory Holes”, down which inconvenient truths of history can be dropped and forgotten, was introduced into fiction by George Orwell in 1948, in his classic dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. Memory Holes were eventually opened up in the real world (or at least, the internet) by the Orwellian powers of the European Court of Justice in 2014.’

In its landmark ruling of May 2014, the European Court of Justice upheld the so-called ‘Right to be Forgotten’ by ordering Google to remove a link to a Spanish newspaper article. A Spaniard, Mario Costeja Gonzalez, wanted to bury a 1998 report that his house was to be auctioned off to pay his debts. Señor Gonzalez complained that, anytime anybody Googled him, this embarrassing reminder of past financial difficulties was still prominent among the search results. He not only wanted to forget about that episode, but wanted to force everybody else to forget about it, too, by effectively purging it from the internet. Europe’s top court concurred and insisted the rules would be enforced across the web.

What harm could it do to allow anybody to draw an online veil over their past indiscretions? And what does gawping at other people’s embarrassments have to do with free speech, anyway? In fact, the EU’s ‘right to be forgotten’ ruling has far-reaching implications for freedom of expression online, potentially stretching over the Atlantic and right around the worldwide web.

The European law gives individuals and institutions the right to demand that search engines such as Google must de-list postings containing ‘outdated’ or ‘irrelevant’ information. The Euro authorities insist that this cannot be construed as censorship, since the material will not actually be removed from the internet – it will simply not be linked to by Google and Co anymore. When plans for these regulations were first announced in 2012, the European Commission’s vice-president said: ‘It is clear that the right to be forgotten cannot amount to a right of the total erasure of history.’ That sounds like rewriting history. If material is not listed by search engines, it is effectively invisible to most online and ceases to exist as public information.

No, no, say the authorities, of course we are not banning this controversial book! We are simply ordering all libraries and bookshops to remove it from their shelves and websites forthwith. You will still be at liberty to read it – if you can find a copy anywhere, or even spot a reference to its existence . . .

Supporters of the right to be forgotten will insist that ‘this is not a free-speech issue’. They claim that the EU’s new rules are intended simply to defend the privacy and personal data of innocent people, not to encroach on anybody else’s freedom. Today, nobody ever admits that they are attacking freedom of expression. They are only ever upholding the inalienable rights of some victims – even if it is, in this case, the hitherto unheard-of ‘right’ to be forgotten and erased from the internet. But the right to be forgotten is a free-speech issue. It strikes at both the historic freedom to report the truth – and the liberty to read it, and to remember.

The right to report events and put history on the record has long been a central part of the struggle for freedom of expression and of the press. One of the first great fights for that freedom in Britain was the eighteenth-century campaign fought by John Wilkes and other heroes for the liberty to publish reports of what politicians said in parliament. That battle was eventually won, after Wilkes and his allies had been imprisoned, sent to the Tower of London and outlawed, and 50,000 Londoners had rioted outside parliament in their support. Until then, it was illegal for anybody to expose what His Majesty’s Government was up to behind the walls of the Palace of Westminster. Britain’s rulers ruled in effective secrecy – and were determined to retain their right to be hidden from history, or at least to write their history as they saw fit.

The right to record and to remember what has happened, and who did what to whom, is a crucial component of the freedom of expression. And there is a flipside to freedom of speech that is far too often forgotten. That is the right of the reader, listener and viewer to access all of the facts and every side of an argument, and then to judge for themselves what they believe to be true.

The ability of the reader or viewer to act as a morally autonomous adult is as vital a freedom as the liberty to speak. It means making choices and decisions on the basis of all the available information and ideas, without intervention from any other parental figure saying You-can’t-read-that. The ‘right to be forgotten’ undermines both sides of the free-speech principle – the ability to tell and record the truth as you understand it, and the freedom to think and to judge everything for yourself.

Everybody has things in their past they would rather erase from memory. That’s life, and it can be tough. The ‘right to be forgotten’ is too high a price to pay for retrospectively trying to protect somebody’s feelings.

Such an attempt at mass memory-erasure echoes Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. In Orwell’s novel, Big Brother’s system of authoritarian control was brutal. As O’Brien of the Thought Police tells the protagonist, Winston Smith, ‘If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever’. But it is not just about brutality. It also involves thought control and the manipulation of history. One of Big Brother’s slogans is, ‘Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past’.

To that end, Winston Smith’s job at the Ministry of Truth involves continually rewriting and deleting articles from past editions of the official newspaper, The Times, so that the historical record will suit the regime’s current political needs. The fact that today’s mortal enemies had been yesterday’s close allies can be conveniently removed from the records; and a former leading Party member who has fallen from favour can have his past achievements erased from official history overnight. The slots into which these excised stories are stuffed are nicknamed ‘memory holes’:

‘When one knew that any document was due for destruction, or even when one saw a scrap of waste paper lying about, it was an automatic action to lift the flap of the nearest memory hole and drop it in, whereupon it would be whirled away on a current of warm air to the enormous furnaces which were hidden somewhere in the recesses of the building.’

Later, when O’Brien tortures Smith, the member of the Thought Police produces a photograph that Smith knows is evidence of a cover-up by the ruling Party. Then O’Brien stuffs the evidence into a memory hole, and denies that it ever existed or that he has any memory of having seen or destroyed it. ‘“Ashes”, he said, “Not even identifiable ashes. Dust. It does not exist. It never existed.”’

True, the EU court has not ordered any torture or sanctioned any stamping of boots on human faces. Europe’s highest court has, however, brought to life something that Orwell could only fictionalise, and in the heart of the democratic West. Its legal endorsement of the ‘right to be forgotten’ risks creating huge memory holes at the heart of the internet, into which people can cast all manner of unwanted memories and facts from the past.

It sometimes seems as if, on one hand, our culture is unhealthily obsessed with alleged conspiracies and sex crimes from the distant past, often based on little more than rumour and gossip. On the other hand there is a willingness effectively to erase hard but inconvenient facts about the recent past from the internet. In this context the ‘right to be forgotten’ is not just a narrow legal problem, but reinforces a wider culture of conformism and if-in-doubt-take-it-down on the worldwide web.

We should remember (if we are still permitted to) that the internet has been such a boon to writers and readers partly because it made it so much easier to research and recall what has been said and done. The old cliché about today’s newspapers being disposable, ‘tomorrow’s fish-and-chip wrappers’, is no longer true – what is written or reported in the press and elsewhere can now be there for good, for all to see, paywalls allowing. Some are obviously uncomfortable about this. But that’s no reason to allow them to use the modern language of exaggerated ‘rights’ to turn recent history into today’s disposable fast-food wrappers.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by Harper Collins. (Order this book from Amazon(USA) and Amazon(UK).)

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.