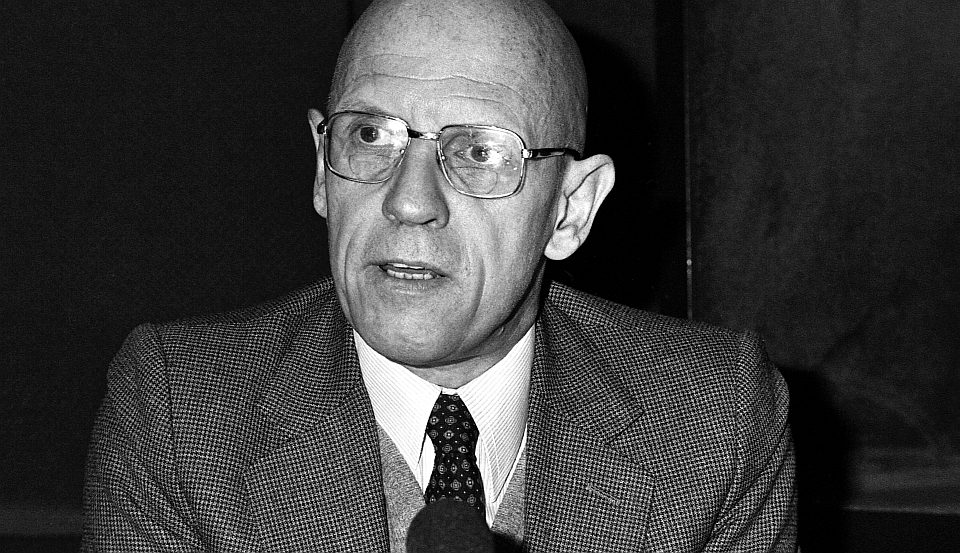

Foucault: from libertine to neoliberal

Was the French philosopher really a Reaganite in poststructural clothing?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘Was Foucault a neoliberal?’ So asked an accusatory headline the other day in Le Nouvel Observateur, France’s centre-left news weekly. It’s a grave allegation. ‘Saint Foucault’, as the article sarcastically calls him, was a heavyweight figure in the humanities, and his theories about truth and power have filtered down into society’s mainstream. He remains a legend of postwar philosophy in France, and queer theory in general. To accuse him of Anglo-Saxon right-wingery is tantamount to lèse majesté.

Michel Foucault popularised the idea that power and truth are intimately intertwined, and that who is making a statement is as important as what is being said. As he wrote in his iconic 1975 text, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Surveiller et Punir: Naissance de la Prison): ‘It is not the activity of the subject of knowledge that produces a corpus of knowledge, useful or resistant to power, but power-knowledge, the processes and struggles that traverse it and of which it is made up, that determines the forms and possible domains of knowledge.’ Truth is perspectival: it is the mere creation of the strong. Might makes right. Power is knowledge.

Several generations of teachers, social-policy strategists, professors and politicians would have been taught Foucault at university at the height of his academic celebrity in the 1980s and 1990s. His thoughts have been widely disseminated as a consequence.

Foucault said that power was omnipresent. Hospitals and schools are no better or worse than factories or prisons: all are based on the same desire to inspect, classify, control, monitor. A security camera is a manifestation of power in action, but so, too, is a restaurant menu or a double-yellow line on a road.

Today, the idea of ubiquitous, invisible power has spawned ‘safe spaces’ on campuses and ‘trigger warnings’ in books. Without Foucault, we wouldn’t have had creations such as ‘ethnomathematics’, which challenges white, patriarchal scientific discourses of knowledge. Another Foucauldian legacy is ‘check your privilege’, a phrase that follows from his line that your truth is bound up with power and status.

Foucault famously wrote of nineteenth-century utilitarian Jeremy Bentham’s grim panopticon, the all-seeing prison in which the inmates responded to never knowing when they were being watched by internalising the coercive demands of the watchman. Foucault saw the panopticon as the embodiment of modernity. The narcissistic idea that we are all being observed by nebulous forces who have a fantastic interest in our lives has brought forth the likes of Julian Assange, Edward Snowden and other such paranoid egomaniacs.

Le Nouvel Observateur asserts, however, that Foucault’s influence extends across the board. So, as well as influencing the liberal left, his teaching also anticipated the Reaganite-Thatcherite neoliberalism that was emerging at the time of his death in 1984. Silicon Valley is not far from the gay clubs Foucault used to frequent in San Francisco. And from California emerged the idea that everyone could do their own thing, regardless of – and often in opposition to – the state. Foucault and today’s billionaire tycoons share a deep, ultra-libertarian hostility to statism.

Yet I don’t believe Foucault can be called a neoliberal. Beyond campaigning for prison reform, he didn’t profess much of a political ideology. If anything, he could be called an anarchist or a libertine. He was a champion of deviancy. He would have been aghast at the idea of gay marriage, and the notion of seeking to render gay relationships ‘normal’.

Just as socialist revolutions invariably end up as dynastic tyrannies, things often turn out contrary to one’s intentions. I wonder what Foucault would have made of safe spaces, trigger warnings, Twitter witch-hunts, the demonisation of flags, censorship on the grounds of ‘hurt’, covering-up lads’ mags, banishing males from debates or the socially acceptable ‘othering’ of today’s deviants: the ‘chav’ white working class, Daily Mail readers, UKIP supporters and the obese. Foucault wrote about the use and abuse of power. It’s worth keeping in mind that its misuse by individuals and groups can be just as insidious as that of any state or government.

There is no ‘real’ Islam

‘The abiding lesson of the long and bloody history of Islamism is that this vile parody of true religion cannot be destroyed by outsiders.’ So thundered The Times at the weekend. It agrees with David Cameron and others that Islamism is some kind of abhorrent perversion.

This discussion about the ‘real’ nature of Islam, and whether it is essentially a peaceful religion or not, is false from the start. Islam, or any religion, has no ‘essence’. It’s not as though a ‘real’ religion was made in a factory and now people are going round hawking counterfeits. A collective faith is merely what people say it is. Some followers of the Prophet Muhammad do carry out murders, while most don’t. Some are like those those brave Tunisians who confronted the Islamist gunman last Friday (and contrast their actions to those Londoners who just stood by and made videos when Drummer Lee Rigby was attacked and chopped up in Woolwich two years ago).

This obsession with the real nature of Islam is born of the same mistaken Platonic essentialism that drives these militant Islamists in the first place. ISIS-inspired jihadists murder Shia Muslims because they see the Shia interpretation of the Koran as fraudulent. Shias aren’t deemed ‘real’ Muslims.

In these matters, it would be better if we all divest ourselves of the chimerical pursuits of purity and authenticity. To call Islamism a ‘perversion’ is like saying American English is a perversion of real English. Both are variants, not ‘distortions’. Islam is neither a religion of peace nor one of war. It just is.

Climate change is not the end of the world

A charge often levelled at environmentalists is that they don’t like human beings very much. We pollute the planet, treat animals disgracefully, breed too much and are generally laying the foundations for our own demise. I’ll never forget the words of that great animal lover, the late Tony Banks MP, who in 2005 told Parliament that ‘humans represent the most obscene, perverted, cruel, uncivilised and lethal species ever to inhabit the planet’ and that he was looking ‘forward to the day when the inevitable asteroid slams into the earth and wipes them out thus giving nature the opportunity to start again’. Or as the anti-foxhunting, pro-badger, ex-Queen bassist Brian May asked on the BBC’s This Week programme last night, ‘don’t you think we’re vermin on the planet?’.

The arch anti-Humanist philosopher and all round misery guts, John Gray, goes one further. He thinks ‘green thinkers’ are misguided in thinking humanity can even do anything about climate change. ‘To think that human beings can halt this process is a form of anthropocentrism’, he told the Barcelona-based newspaper Ara the other day.

I’ve long since believed that climate change is happening and that human activity is the cause. But I also believe that, unique among living creatures, we also have the capacity to fix it.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. Follow him on Twitter: @patrickxwest

Picture by: PA Images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.