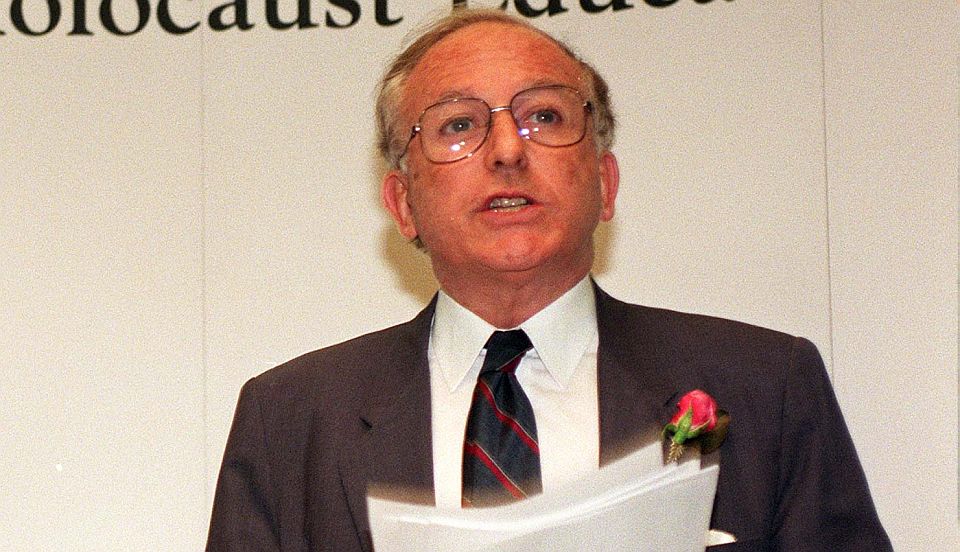

Janner: when therapy trumps justice

A senile old lord is being subjected to a showtrial.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The UK Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has confirmed that Greville Janner will face prosecution for child-sex offences. The original decision of Alison Saunders, the director of public prosecutions, not to prosecute Janner was overturned by the CPS’s own review procedure, which allows complainants to challenge a decision not to prosecute. The QC who undertook the review concluded, contrary to Saunders, that a prosecution of Janner would be in the public interest.

Saunders originally decided that a prosecution was not in the public interest because Janner would inevitably be found unfit to plead. She also decided that a ‘trial of the facts’, which, in lieu of a fit-to-plead defendant, is normally used to establish certain facts for the purpose of passing a sentence of compulsory treatment, would have been pointless in Janner’s case. He is no threat to the public, so compulsory treatment could not have been justified, and he would, therefore, have been discharged. In other words, Saunders found that a trial would not be in the public interest because there was no objective, societal reason to try Janner.

The volte-face has occurred because the review process found that there was a public interest in trying Janner. Yet none of the circumstances around the original decision has changed. He remains unable to prepare his defence. He may not even have to attend court.

So how can it be that a prosecution is now in the public interest? Reading the CPS’s announcement, it is clear that this ‘prosecution’ only makes sense if its purpose is the ceremonial confirmation of the complainants’ experiences. Somewhere, in the annals of the CPS, a lawyer has concluded that the prosecution of a senile octogenarian, for allegations he cannot understand, in relation to events which occurred decades ago, in a trial where almost every aspect is a foregone conclusion, can be justified on the basis that it will bring emotional satisfaction to the complainants.

The emotional needs of the complainants have been the dominant concern throughout the CPS’s dealings with the Janner case. When Saunders made her original decision not to prosecute him, she indicated that she had contacted Lowell Goddard, chairman of the independent inquiry into child abuse, to ‘ensure’ that the complainants could give evidence in the course of the inquiry. This, in itself, was an unusual step, given that witnesses are only usually required to give evidence if necessary for the proceedings. Saunders was in no position to judge whether the witnesses would be required to give evidence. By contacting the chairman to ensure that they would be required, Saunders made it clear that the public affirmation of the complainants’ word was the main objective of any proceedings against Janner.

The CPS’s about-turn shows that Janner will be prosecuted because giving evidence to an inquiry is ‘no substitute for the adjudication of the criminal court’. This peculiar sentence only makes sense if the purpose of the proceedings is publicly to confirm the experiences of the complainants. The only way that the criminal court could represent a legitimate ‘substitute’ for a public inquiry, in these circumstances, is if the review process concluded that the emotional needs of the complainants could not be adequately accommodated by the public inquiry.

This announcement shows that Janner’s case represents the degeneration of our criminal courts into forums of public therapy. In this new system of justice, the truth is irrelevant. The fact that Janner’s evidence cannot be tested means we will gain no greater insight into the actual truth of what is being alleged. In fact, this is not a prosecution in any true sense of the word. The CPS did not use the term ‘prosecution’ in the wording of its announcement – even it recognises that something new is happening with Janner. What is happening is a showtrial to accommodate the emotional needs of the complainants. The defendant, a vulnerable and senile old man, is being dragged through a procedure that has no substantive purpose over and above the public validation of his complainants’ experiences. This is not justice, or a ‘prosecution’ – it is the first brutal showtrial of a new legal system, one in which therapy comes before justice and the truth.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practicing criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. His first book, Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans, will be published later this year.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.